Eckhart Tolle’s portrayal of self-observation owes much to the earlier work of Maurice Nicoll, I argue in an article series introduced below.

Self-observation is a central practice in the work of Eckhart Tolle, a bestselling self-help author considered one of the world’s most spiritually influential living people. My research suggests Tolle’s presentation of this practice owes much to Maurice Nicoll, a Jungian psychiatrist turned Fourth Way teacher whose expansive work was published in the early 50s. Yet in contrast to Tolle’s celebrity, Nicoll is an obscure figure. Few have recognised his influence or considered its cultural significance. This is an introduction to an article series comparing the similar ways Nicoll and Tolle present this self-knowledge practice—and I outline why I think this tells a bigger story.

Comparing Maurice Nicoll and Eckhart Tolle on Self-Observation: An Introduction

Self-observation, a present-moment practice formalised in the West in the early-to mid-20th century, is more pervasive than many realise. But its rise has been a silent one, infusing contemporary spiritual teachings from the background, often unnamed and unrecognised in any official sense. Its source and road to influence is unacknowledged and unknown to many. And its significance is eclipsed by more prominent modes of present-moment practice like mindfulness, which was popularised in the West later, yet blends in many of its attributes.[1] In other words, its story has not been told. I hope this series of articles will help to change that.

Whether you’ve actually heard of self-observation, in the sense I mean it, likely depends on your familiarity with G.I. Gurdjieff’s “Fourth Way” teaching. This tradition exerts a strong but understated spiritual influence in the West, and self-observation is its keynote practice—according to one of its early and formative teachers, the Jungian psychologist Dr Maurice Nicoll.[2] He returns to self-observation again and again in his extensive Psychological Commentaries, written between 1941 and 1953, often emphasising its importance for self-knowledge and inner change.

While most people have never heard of Nicoll, his work casts a long shadow. My research suggests he has influenced, in no small way, the most popular modern spiritual author of our time, Eckhart Tolle, whose bestselling books The Power of Now: A Guide to Enlightenment and A New Earth: Awakening to Your Life’s Purpose have sold tens of millions of copies. When I say Tolle is popular, consider this: he has been ranked among the Pope and Dalai Lama in spiritual influence—and sometimes even ahead of them![3]

Yet despite Tolle’s public stature, Nicoll’s apparent influence upon his work is not widely recognised or acknowledged. While people familiar with the Fourth Way have noted similarities between its psychological teachings and Tolle’s self-help/spiritual message, the scope of these correspondences, as far as I am aware, have not been extensively documented, demonstrated, and brought to light in the methodical way I intend to.

So just how much influence am I talking about? I have a multi-part series of articles planned that will examine just how deep it goes. If the weight of commonalities I outline signifies something more than an extraordinary coincidence—which I think it more than likely does—then the evidence suggests Tolle’s work owes a significant debt to the Fourth Way, and to Nicoll’s presentation of it in particular. In fact, my previous article already demonstrates this with respect to Eckhart Tolle’s notion of the “pain-body”—but that is just one similar concept of many.

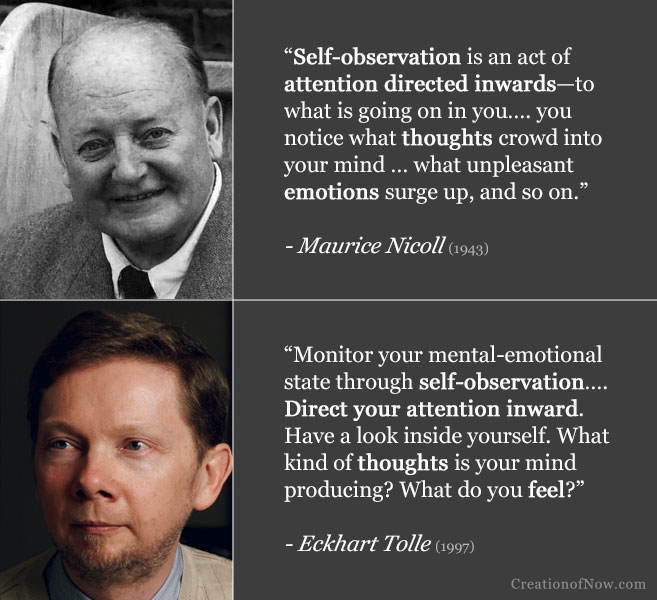

Self-observation involves directing attention inwards to watch your thoughts and emotions, they explain.

I now want to delve into the similarities surrounding the practical method Tolle presents in his work, which is essentially the practice of self-observation. Many fundamentals of the practice are there, even if other parts of Tolle’s message differ. Importantly, in both sources, self-observation is presented as the primary way to see and overcome one’s negative psychological states and effect an inner transformation.

When Tolle uses the specific term “self-observation,” he does so in broadly equivalent ways to Fourth Way sources. However, he uses it sparingly, employing a much looser and varied terminology to describe the same essential act or practice. This mixed terminology is likely one reason the term, and practice it refers to, lacks widespread recognition. In Fourth Way sources, “self-observation” is used with much greater formality and frequency, but since this tradition is obscure to most, the term has not been widely popularised.

Tolle’s mixed terminology can obscure certain commonalities between his work and the Fourth Way at first glance, but such differences are only superficial; go beneath the surface, and there is still much the same in substance. Crucially, the importance of consciously watching or witnessing one’s involuntary mental-emotional patterns and reactions in everyday life, without identifying with these, is a central premise in both sources, even if Tolle does not always call this “self-observation.”

Granted, some of these ideas crossover with a number of other modern sources broadly focused on present-moment awareness, such as latter-day mindfulness literature. However, there are hallmarks to the Fourth Way’s earlier approach to self-observation, and Nicoll’s definitive presentation of it, which stand out from this broader milieu. I intend to highlight noteworthy correspondences in style as well as substance which strongly suggest Nicoll was an important influence on Tolle’s work. I’ll begin exploring these commonalities in much greater detail in my next article.

But before I compare and unpack similarities between how Nicoll and Tolle present self-observation, I decided to write this introduction, as I recognise many potential readers may not be familiar with self-observation, in the sense meant here, or the authors, so some background is called for.

This is a prelude to the comparative analysis I’m yet to publish, to provide some context before diving into detail. I’ve already discussed some of these themes in greater depth before, but this is tailored more as a primer to my forthcoming work.

Both authors refer to the “power of self-observation” and suggest it can be developed with practice.

I realise of course that a fair number of people are familiar with Gurdjieff and P.D. Ouspensky—the noted Russian esotericist who became the former’s most well-known pupil and unofficial literary emissary—as well as the Fourth Way system they promulgated. A significant but probably lesser percentage are familiar with Nicoll too, who studied with both men after leaving the mentorship of Carl Jung to do so. But such enthusiasts represent a rather small minority if we take a wider cultural view.

The modern-day self-development scene has become a multi-billion dollar industry of colossal scale. [4] This self-help/spirituality “industry” now predominates for many over both conventional religion and its classical, and typically more discreet, alternatives in the Western Esoteric tradition to which the Fourth Way belongs—a tradition of mystics, schools and movements which never met with or typically sought a mass market. The rampant commercialism of this modern industry bears little resemblance either to religion or classical esotericism.

Eckhart Tolle stands somewhere at the pinnacle of this industry, reaching a massive, worldwide audience via bestselling books, a lucrative speaking circuit, and various DVDs, CDs, and other products sold on his website, including a pay-walled subscription service.[5] Tolle’s fame is due in no small part to the substantial endorsements he received from TV personality Oprah Winfrey in the 2000s.[6] His celebrity and global reach stands in stark contrast to figures like Nicoll who, while esteemed in certain circles, remains largely unknown. Nevertheless, despite these and other differences, these two authors have something in common: they both emphasise self-observation as being integral to self-transformation, and have many similar things to say about it.

Given Tolle’s phenomenal prominence, my research shows just how much unseen influence Fourth Way ideas and practices may exert on popular strains of contemporary spirituality in our culture.[7] Maurice Nicoll’s formative works exploring the psychological dimensions of this teaching played an important part in this diffusion, taking its self-knowledge principles to a wider, albeit select, readership beyond the Fourth Way fold.

Self-observation was at the heart of this, and my forthcoming comparative analysis will aim to show just how influential Nicoll’s explanations of this practice have been, by revealing significant commonalities with Tolle’s message.

This writing venture is my way of telling the story of the silent rise of self-observation in our culture, and its hidden significance. But before we get to the meat of that story—the evidence of influence—I must first provide some background on what self-observation is and how Maurice Nicoll came to teach it, for those unfamiliar.

If nothing else, I hope from reading this introduction you come away with some sense of why this story should be told.

A Present-Moment Practice for Everyday Life

The whole of the Work starts from a man beginning to observe himself. Self-observation is a means of self-change. Serious and continuous self-observation, if done aright, leads to definite inner changes in a man.

– Maurice Nicoll

Gurdjieff’s Fourth Way teaching outlines a vast cosmology, but the practical psychological aspect is usually termed “The Work.” To “work on oneself” is to use certain methods to gain self-knowledge and effect an inner transformation. The modus operandi is self-observation—the conscious, present-moment observation of one’s own psychological states and behaviour in daily life.

I’ve previously discussed how the Fourth Way introduced a quiet “revolution of the present moment” long before mindfulness was popularised.[8] This teaching came to the West in the early 1920’s after its initial advocates fled the Russian Revolution. Unlike now, Western society was not then saturated with Eastern-inspired spiritual practices, nor had eclectic mind-body-spirt shops sprung up in every major shopping area. Certain cultural predecessors to these existed, but they were much more niche, exclusive or underground compared to today. I think they were generally more theory-orientated too; Gurdjieff offered a quite different approach to what was typically on offer in more popular forms of western esotericism of the period in the English-speaking world.

While Gurdjieff’s system included philosophy and cosmology, its centre of gravity was more practical—which in itself set it apart then.[9] It centred on how to change and raise one’s level of consciousness in the present moment. Self-observation was central to the Fourth Way’s present-moment revolution. It was to be practiced in conjunction with self-remembering, the deliberate act of self-awareness—to be “present” in the moment. Gurdjieff maintained we are “asleep” to ourselves most of the time, lost in an unconscious stream of automatic reactions, thoughts, attitudes and behaviours. Self-remembering is the act of waking up from this mechanical state. One brings the fullness of their attention into the present moment, coming out of their habitual daydreams and automatised reactions, like waking from a dream. One comes back to oneself and is present to oneself—hence the name, self-remembering.[10]

This self-remembrance was to be done in conjunction with the closely-connected practice of self-observation, which Gurdjieff called “the chief method of self-study.”[11] With this exercise, one directs a part of their attention inwardly and remains vigilant, watching habitual reactions in thought, feeling and behaviour as they occur in daily life, but always with detachment, or, to use the preferred terminology, without identifying with what is observed. One maintains awareness of the world around them while doing this, but makes an effort to be aware of their inner states and reactions while going about their lives.[12]

Indeed, a key feature setting The Work apart from more familiar religious contemplative traditions—like those from which mindfulness or similar meditative practices are derived—is the primacy it gives to regular life. The Fourth Way derives its names from this difference: unlike the more recognised “three ways” of the fakir, monk and yogi, whose ascetic adherents typically renounce possessions, family ties and withdraw from common life—perhaps to deserts, monasteries or mountain caves for contemplative practices—Gurdjieff’s “fourth way” was primarily to be carried out in action, in the world, in regular life. [13] Instead of retreating from the world, one faces it in a different way and practices “in the midst of life”.[14]

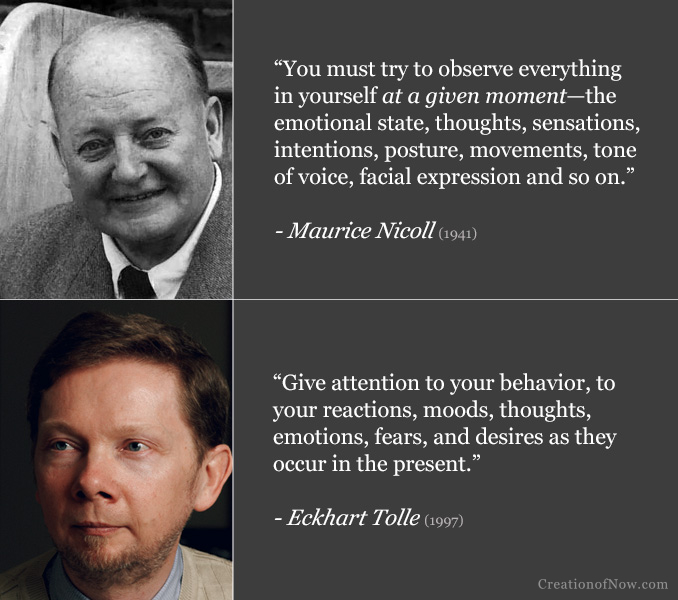

We are told to watch our inner states in the present moment, as they occur.

Self-observation is intrinsic to this different, more conscious, way of living in the world. The idea is that by maintaining a discipline with self-remembering and self-observation, one begins to see characteristics that stand in the way of one’s self-development as they arise in daily interactions and events, such as negative emotions. Having awareness of these factors allows one to study them in action, and brings the possibility of changing and responding to life in more conscious ways. This self-knowledge process is embedded in a wider framework of inner transformation involving the conservation and transmutation of one’s energies.[15]

With his background in Jungian psychiatry, Maurice Nicoll was uniquely placed to communicate the practical self-knowledge teachings of the Fourth Way. Nicoll had been a close friend and pupil to the renowned Swiss psychologist Carl Jung, who was godfather to his daughter. But Nicoll soon moved on from being a public exponent of analytical psychology to focus on the Fourth Way once it arrived in London. He even gave up his successful Harley Street psychiatry practice at the time to do so. As mentioned, he went on to study with both Gurdjieff and Ouspensky in person. In 1931 the latter tasked Nicoll with teaching the system independently; Nicoll did so until his death in 1953.[16]

Most of Nicoll’s written expositions of the teaching are contained in his Psychological Commentaries on the Work of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky, a five-volume anthology of weekly lectures written between 1941 and 1953. (The sixth volume is an index compiled later.) It is these volumes that pertain most directly to self-observation, the value of his other works notwithstanding.

Nicoll’s commentaries bring a relentless focus and acumen to conveying self-knowledge practices and principles, especially self-observation. While Jung also extolled self-knowledge, and had his own ideas about how to obtain it, Nicoll, as a Fourth Way teacher, came to emphasise self-observation as the primary means to acquire it, as Gurdjieff had. “Inner change … is only possible through self-observation and the self-knowledge that comes from it,” Nicoll tells us.[17]

So though Nicoll continued to agree with Jung on the importance of self-knowledge, and his personal background with him undoubtedly enriched his expositions, he came to pursue it via a different method to analytical psychology. He believed the Fourth Way offered a more complete system for this purpose. Jung continued to be an influence, however; Nicoll acknowledges him as his “first psychological teacher” and infused certain Jungian elements into his commentaries while harmonising them to the “esoteric psychology” he extolled.[18] This is perhaps most apparent in Nicoll’s discussions of dreams as providing meaningful insight into one’s psychology.[19] Nevertheless, self-observation was still unmistakably the primary method he emphasised.

“The object of self-observation is to enable us to change ourselves. But its first object is to make us more conscious of ourselves. Only by making ourselves more conscious to ourselves does it enable us to begin to change ourselves.”[20]

“Remember, a thing in you cannot change if it remains unconscious to you. So the Work begins with self-observation. If you cannot observe a thing in yourself you cannot change it. Always remember this. Only the light can cure you—and the light means the light of consciousness.”[21]

Indeed, to say that Nicoll emphasises “the great and inexhaustible subject of self-observation” would be an understatement.[22] He returns to it again and again in his commentaries, even starting one lecture by explaining why he needs to keep on discussing it, even though people might think they’d heard it all before.[23] Self-observation is “the continual task of all connected with my Branch of this Work,” he once declared. [24]

This gives some background to the coming comparisons. For my premise, as already stated, is that the Fourth Way, and Maurice Nicoll’s presentation of it in particular, has had a profound unrecognised influence upon Eckhart Tolle’s work, especially with the practice of self-observation. When it comes to the practicalities of how to actually do this and what it entails, there is much in common, even if other aspects of Tolle’s message, including some of his New Age beliefs, may differ somewhat or even markedly.

I must emphasise here that self-observation is not presented as a mental concept to be accepted or rejected, but a practice—that is, something that you do, a mode of consciousness you learn to shift into. This has nothing to do with intellectualism. Practicing self-observation versus knowing about it conceptually is as different as riding a bike is from thinking about it. “You may hear about self-observation all your life,” Nicoll tells us, “but there is always a great gap between hearing and doing.” He often emphasised its practical nature, pointing out, “only you can observe yourself” and posing rhetorical questions like, “Have you observed anything in yourself this week?” He stressed that just believing or parroting ideas of The Work gets one nowhere—you must “practise them … apply them to yourself” and “see the truth of The Work internally” for it to become “a process taking place in you and changing you.”[25]

Unless you have got to the point of understanding that this Work, and all esoteric psychology, is about your inner states and deals with your reactions to others who act on you, it will all seem vague, fantastic and unnecessary. Self-Observation, the starting-point of this Work, is to make one realize one’s inner states. Evolution is an evolution of inner states. Self-development is a development of inner states. Only you can know your inner states: only you can separate from useless, negative or evil states. I repeat that it is impossible to become more conscious … unless you have begun to be aware of what kinds of things are in you and go on in you, and for this to occur it is necessary to turn the attention inwards first of all and notice your reactions to the outer. But you must also notice the outer.[26]

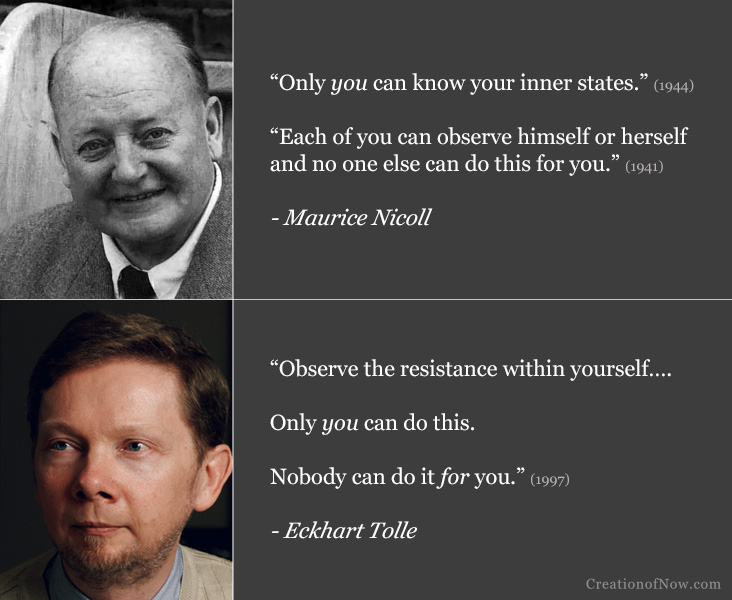

Nicoll’s practical advice that “only you”[27] can observe your inner states and “no one else can do this for you”[28] is echoed by Tolle. When instructing the reader to observe their emotional state, Tolle likewise writes: “Only you can do this. Nobody can do it for you.”[29]

Both authors stress that only you can observe your own states—no one can do it for you.

Given how famous Tolle has become in comparison to earlier teachers of these ideas like Nicoll, it is worthwhile taking a closer look at the cultural origins and significance of self-observation in the modern West. For it’s possible that many with an interest in this sphere may find the practice somewhat familiar, or perhaps have indirectly heard of it without fully realising it—let alone understanding its cultural origins and journey from obscurity into the limelight.

Indeed, outside of conventional religion and secularised meditation or yoga exercises, self-observation just might be the most popular spiritual practice of our time most people haven’t heard of. Its pervasiveness can be largely ascribed to Tolle’s phenomenal success. Likewise, its lack of overt visibility can perhaps be ascribed, at least in part, to Tolle’s apparent circumspection about declaring his influences.[30] But while certain of Tolle’s other influences have been recognised, the Fourth Way’s influence on him is not widely acknowledged, even though, I believe, it is significant.

To show that self-observation, as taught in the Fourth Way, is indeed a real and present influence in Tolle’s message, I’m going to explore the multi-faceted correspondences between the work of Nicoll and Tolle in presenting this practice—which both uphold as being integral to inner transformation. I will highlight similar concepts, descriptions, advice, and tips on how to approach it, and the use of similar terms and phraseology too. I will break down these correspondences in a series of articles focussing on key themes. While certain points, taken in isolation, are more general and could be attributed to other sources, many are either quite distinct in themselves or presented in a rather idiosyncratic way. But it is the total constellation of commonalities that is most persuasive. Considered together, the cumulative evidence, I believe, strongly suggests that Tolle was indeed influenced markedly by the Fourth Way.

As already mentioned, I’m certainly not the first to notice this in a general sense, but I may be the first to document it to the extent that I intend to—and highlight Nicoll’s particular importance in the process.

The first part of this series has been published, and is where the in-depth comparative analysis on this topic begins.