Information on mindfulness or present-moment awareness is widespread today. Sources range from the religiously orientated, to the secular, to glossy New Age bestsellers seemingly offering enlightenment. Many emphasise having awareness in life’s everyday activities, not just in formal meditation sessions or secluded retreats. From where does this trend originate? Here I argue it owes something to the Fourth Way, an early 20th century spiritual tradition advocating what once seemed a radical idea: that spiritual development was best pursued in ordinary daily life, through consciously observing and changing one’s inner and outer reactions to life’s events in the moment.

“Man is a machine.” These stark words from Gurdjieff commence a notable “red pill moment” in modern esoteric literature. Ouspensky wasn’t entirely convinced at first, nor did he fully grasp what his perplexing new acquaintance really meant. That came later. A Russian journalist and writer on esoteric topics, Peter D. Ouspensky had recently returned from travels in search of higher knowledge in the East. He wasn’t expecting to find what he’d sought elsewhere back home, and was somewhat sceptical of the prospect. Yet that is what George Ivanovich Gurdjieff, an enigmatic mystic from Armenia, seemed to be offering.

It was Moscow, 1915, a time of tumult. The First World War was raging, and the spores of violent revolution were fomenting at home. The war was bad enough—then unparalleled in its scale and devastation—but relative civility still held on the home front. In just a few years, however, the Bolshevik Revolution would churn all of Russia into a cauldron of chaos and violence, forcing Gurdjieff, Ouspensky and their associates to retreat westwards. Not even Ouspensky, a keen observer of his country’s social and political affairs, could then have guessed how bad things would get. These would be his last years in his homeland before the Russia he knew disappeared.

It was this strange time and place in human history—an eerie interlude between the outbreak of world war and a revolution of terror—which serves as the backdrop to a classic of 20th century esoteric literature, Ouspensky’s In Search of the Miraculous, Fragments of an Unknown Teaching. Told through Ouspensky’s eyes, the book is often considered one of the best introductions to the views of Gurdjieff.

It begins with Ouspensky briefly telling of his travels and life as a seeker, before his fateful encounter with Gurdjieff in Russia, where the latter had recently begun his teaching career. Eventually joining Gurdjieff’s circle himself, Ouspensky finds himself opened to a new vision of life, and details what he learned in those intensive years of study. The book’s final act covers the fellowship’s exodus to Western Europe, after intervals in the Caucasus and Turkey, with Ouspensky finally parting ways with Gurdjieff at the end.

A dramatised depiction of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky talking in Russia, from the short film In Search of the Miraculous: Fragments of an Unknown Teaching (1998) based on the book.

Despite the dramatic events surrounding the protagonists, the book is mainly an exposition of Gurdjieff’s system, in his own words, as recounted by Ouspensky, with the addition of the latter’s personal reflections on the sometimes very dense philosophical material. Ouspensky skillfully narrates the gradual revelation of what he called the “fragments of an unknown teaching” which came by way of Gurdjieff’s discussions and talks. The source of this teaching Gurdjieff was always circumspect about when Ouspensky asked, although he did inform him he’d made “several long journeys in the East” since his youth “in search of knowledge and the people who possessed this knowledge.” Gurdjieff conveyed that “after great difficulties, he found the sources of this knowledge in company with several other people who were, like him, also seeking the miraculous,” Ouspensky tells us. He could never decide exactly what was true in these stories, as “a great deal was contradictory and hardly credible,” but he nevertheless believed Gurdjieff had found and “undoubtedly possessed” the knowledge about which he spoke, even if he was vague and indefinite about its source.[1] As the book develops, and this mysterious teaching is gradually unfolded through Gurdjieff’s discourses, we see Ouspensky’s understanding develop in parallel.

Ouspensky comes to grasp the heart and significance of Gurdjieff’s message: humanity is asleep. The so-called “waking state” we live in day by day is actually a state of unconsciousness, according to this view, in which we function primarily by rote mechanical reactions to what happens rather than acting from consciousness. This is what Gurdjieff meant by people being machines. But, importantly, he outlined a method for individuals to rectify this. He detailed a complex cosmology also, but the “work on oneself” he proposed began with making conscious efforts to wake up from automatism and pay attention in the present moment in daily life.

As I’ve pointed out before, the practicality of Gurdjieff’s system, also known as the Fourth Way, made it unique in the West in the 1920s in its field. Notions of transformation, awakening and perceiving a greater reality could be found in western esoteric and spiritual literature and associations available at the time, but such ideas were generally discussed in more abstract, philosophical or academic terms or, in older sources, couched in mythology or symbolism, which made it obscure. Such material may be inspiring, and have the ring of truth, but lacked clear guidance on what to practically do to awaken.

Yet being asleep and mechanical were not mere abstract concepts to be believed in, contemplated or discussed in Gurdjieff’s system, but a vivid reality one was encouraged to actually perceive for oneself, by direct experience, through specific exercises—namely self-observation and self-remembering. By creating the discipline of being more conscious and observant in the present moment in everyday life, one could, it was held, both awaken to the workings of one’s unconscious processes, study them in action, and gradually transform oneself to become more conscious. There was much more to Gurdjieff’s message than that, of course, but this emphasis on present moment practice, namely, taking in the impressions of life consciously moment-by-moment, to bring awareness and the possibility of change to the very moments one lives—to each instant where one ordinarily reacts mechanically—is what I wish to focus on here.

Anyone faintly familiar with the modern mindfulness movement would recognise it shares some obvious similarities with the approach I just summarised. Mindfulness is a form of present-moment awareness practice, derived primarily if not exclusively from Buddhism, which became popular in a more secularised form in the 1990s. There are differences, some of which I’ll come to later, but there is a common emphasis on directing one’s attention to the present moment and responding with greater awareness or mindfulness. In tandem, there has also been a surge in popularity of New Age works concerned with present-moment awareness from around the early 2000s, which continues today. In both cases, the interest has been substantial and pervasive. It is perhaps surprising then that the connections these latter manifestations in the West share with the earlier emergence of the Fourth Way is not more widely recognised and discussed.

I intend to look now at the similarities and differences between the approaches outlined by Fourth Way teachers and later appearances of present-moment practice in the West. I’ll highlight some indications Fourth Way methodology has had an enduring influence on popular forms of this today—including some of the most commercially successful New Age iterations. Fourth Way methods, I believe, carry more influence and relevance than is commonly appreciated.

Waking Up from Sleep

The idea people are somehow asleep in the usual so-called “waking state” of daily life is a central theme running through In Search of the Miraculous and Gurdjieff’s teachings more broadly. Gurdjieff points out there is little inner difference between this state and that experienced during nocturnal sleep, apart from the capacity for physical movement.

Both states of consciousness, sleep and the waking state, are equally subjective. Only by beginning to remember himself does a man really awaken. And then all surrounding life acquires for him a different aspect and a different meaning. He sees that it is the life of sleeping people, a life in sleep. All that men say, all that they do, they say and do in sleep. All this can have no value whatever. Only awakening and what leads to awakening has a value in reality.[2]

I mentioned Ouspensky was “red-pilled” to this perspective, as the saying goes, although that saying did not then exist of course. But it is apt. In The Matrix film, people are controlled by mechanical forces—actual machines—and cannot perceive it, seeing only a false dream of “waking life” as their bodies sleep, their minds plugged into a dream world. However in the view Gurdjieff outlined people are or have become machines themselves— automatized creatures—yet the mechanical forces keeping them unconscious in so-called waking life, blind to their state and reality, are primarily built up within them. This inner slavery is reinforced by external influences people are near helpless subjects to in this state. With almost everyone caught in this state, there is inevitably unnecessary suffering and destructiveness at global scale, according to this perspective.

Neo, played by Keanu Reeves, takes the red pill in The Matrix (1999)

In both The Matrix and Gurdjieff’s view, humanity’s mechanical sleep is reflexively upheld and instilled by society, as it is the norm. And in both cases, being unconscious results in a great loss of one’s energies, which are unfortunately redirected towards sustaining the very mechanical forces that keep one asleep. Yet in both cases, people can wake up from their torpor, understand their condition, and work to unlock their inner potential that would otherwise remain dormant and almost completely unknown. Only the inexplicable feeling that something is wrong or missing drives someone to seek a higher form of knowledge they innately know and feel must exist, that will somehow provide a way out.

All these parallels, and more, are evident in Gurdjieff’s work. Of course, the idea humanity is somehow ignorant and trapped in illusion, unable to perceive a greater reality, is a recurring metaphysical and mythological theme of antiquity. It can be seen, for example, in Plato’s allegory of the cave, in Hermetic and Gnostic perspectives, and in Eastern teachings about Samsara or Maya (illusion). Many of these sources informed The Matrix series.[3] Gurdjieff also stated plainly that the idea of waking from this sleep—a sleep of perception—is nothing new, and even features prominently, though largely unrecognised, in the Christian Gospels:

There is nothing new in the idea of sleep. People have been told almost since the creation of the world that they are asleep and that they must awaken. How many times is this said in the Gospels, for instance? ‘Awake,’ ‘watch,’ ‘sleep not.’ Christ’s disciples even slept when he was praying in the Garden of Gethsemane for the last time. It is all there. But do men understand it? Men take it simply as a form of speech, as an expression, as a metaphor. They completely fail to understand that it must be taken literally. And again it is easy to understand why. In order to understand this literally it is necessary to awaken a little, or at least to try to awaken. I tell you seriously that I have been asked several times why nothing is said about sleep in the Gospels. Although it is there spoken of almost on every page.[4]

As Gurdjieff notes above, the necessity of waking from sleep in ordinary life was not widely recognised in any real practical sense by most people in the Christian world. But even if one did grasp it on some intellectual level, what was one to actually do about it? In the early 20th century there was not much to go by, in the West at least, by way of a practical methodology, until Gurdjieff’s system came along.

This is highlighted by Ouspensky’s reception of Gurdjieff’s premise. It struck him as one of the most startling and significant ideas he had ever encountered. What’s more, he was well-travelled, educated and familiar with a wide range of scientific, religious, philosophical and esoteric perspectives of both East and West. This included Theosophy, a popular form of syncretic esotericism in Russia and the West in those times. Yet he grasped that everyone seemed to miss the important central point Gurdjieff highlighted:

European and Western psychology in general had overlooked a fact of tremendous importance, namely, that we do not remember ourselves; that we live and act and reason in deep sleep, not metaphorically but in absolute reality. And also that, at the same time, we can remember ourselves if we make sufficient efforts, that we can awaken.[5]

He also describes trying to explain this idea to people he considered intelligent, but was at first perplexed that very few could actually grasp the “magnitude of the idea” concerning “the absence of consciousness [in our lives] and the idea of the possibility of the voluntary creation of this consciousness.”

And this brings us to the practices Gurdjieff called self-remembering and self-observation. It is only by making the effort to become conscious and aware in the present moment—to remember oneself—and also look within and observe all the mechanical reactions that arise within in daily life and keep one in “deep sleep,” without identifying with them, that one begins to see the truth that one is actually unconscious and living mechanically most of the time. As Gurdjieff points out, one must “at least to try to awaken” to see this fact. A similar idea is portrayed in The Matrix: one cannot simply be told what the matrix is—it cannot be grasped hypothetically—one has to actually see it in operation for themselves to understand. Then one knows what they are up against and must overcome.

After his red pill, Neo wakes up in a pod and soon comes to realise he’s spent his entire life unconsciously enslaved by mechanical forces feeding off his energy–and nearly all of humanity is asleep in this state.

Ouspensky did try the exercises Gurdjieff explained, did see the truth of this state of affairs for himself, realised how difficult it was to actually be and stay conscious—and was shocked.

The Fourth Way Approach: The Transformation of Daily Life

“The Gurdjieff work … focuses on developing mindfulness in daily life,” writes transpersonal psychologist Dr Charles T. Tart. Called “the fourth way”, this approach particularly emphasises developing greater consciousness in ordinary everyday events and activities. This was in contrast to more well-known avenues of spiritual practice in religious traditions, where, if mindfulness is practiced, it is usually in a more rigid and formalised way, often in a monastery or ashram where adherents lead highly specialised lifestyles away from ordinary life. But this method was meant for ordinary life. Tart provides a useful valuation of its objects and benefits:

A conditioned way of perceiving the world categorizes situations simplistically and evokes habitual responses, both inwardly and outwardly…. Our habits of perception, thought, feeling and acting lead us into many mistakes.

Yet it is possible to learn to be mindful in our daily lives, to see more accurately and discriminatingly and to behave appropriately toward others and our own inner selves. The results cannot be fully described in mere words, but words like freshness, attentiveness, beginner’s mind, perceptual intelligence, or aliveness point in the right direction. A stale, narrow life of habit and conditioned perceptions, feelings, and actions can slowly be transformed into a more vital, more caring, more effective, and more intelligent life.[6]

This emphasis on bringing this kind of practice into daily life is behind the name “fourth way.” Gurdjieff identified three major categories of spiritual schools, or “three ways,” that most systems fell into, and differentiated the fourth he advocated from these.

The first he called “the way of the fakir.” In this category, ascetics seek self-development through dominion over the body, by enduring painful physical rigours—like standing still on one leg, or with arms outstretched and unmoving, for long periods of time. Gurdjieff said such people develop great willpower, but not the understanding or intelligence to direct it more usefully.

The second is “the way of the monk” found in monastic traditions. Monks can cultivate richer inner feelings, due to their daily religious discipline immersed in prayer, ritual and reverence. However, Gurdjieff believed they typically failed to develop knowledge sufficiently, so this second way tended to create “stupid saints”—people with the best of intentions, but insufficient understanding to apply it well.

The third way he called the way of the yogi, where development is sought through the mind. The particular meaning he gives the word “yogi” here differs from common associations—it can be used in much broader ways. But Gurdjieff applied it to those who seek higher knowledge through the mind. Those who cultivate great conceptual knowledge of religious or spiritual ideas, texts, theology, philosophy etc. would fall into this category. It also apparently includes those dedicated to mental training exercises, such as intensive and prolonged meditation practice. The third way, he claimed, tends to neglect the development of practical bodily and emotional intelligence, creating the problem, as Gurdjieff put it, that a person “knows everything but can do nothing.”

These three ways, he maintained, are respectively connected with a person being centred more in their body and instincts, their emotions, or their intellect—which denote particular psychological centres in the system he outlined. Most people in the world are typically centred in one and less developed in others, he claimed, therefore those who seek self-development tend to pursue an approach corresponding to their own category—bodily, emotional or intellectual.

Despite their differences, a weakness all three ways shared, Gurdjieff held, is that they produce a one-sided development, where particular features are strongly developed, but overall development is incomplete.[7] Because they do not produce well-rounded or balanced development of all faculties, he felt that they typically do not enable full development to occur. Tart provides a summary of the professed benefits of the fourth way over the other three in this respect:

Intellectuals try to solve almost all problems in life in terms of thought. But there are times in life when you have to use your body and push, and there are times in life when you have to listen to feelings. Emotional types tend to try to solve all problems in life in terms of making things feel right, but there are times in life when you have to abstract yourself from feelings and intellectually analyse, and times when you need to tap your body’s intelligence. Bodily types try to use willpower to push through everything, but there are times when you need to listen to feelings or to think about problems. Gurdjieff’s attempts to develop mindfulness, therefore, also centred around developing all three aspects of oneself, so that one comes up to a relatively normal level intellectually, emotionally, and bodily/instinctively. That kind of balanced development is central to the Fourth Way.[8]

The other weakness of the three ways, Gurdjieff believed, derived from a commonality all shared: the requirement of a special life of renunciation. They are not designed to be applied to life as it is. As he puts it:

They all begin with the most difficult thing, with a complete change of life, with a renunciation of all worldly things. A man must give up his home, his family if he has one, renounce all the pleasures, attachments, and duties of life, and go out into the desert, or into a monastery or a yogi school. From the very first day, from the very first step on his way, he must die to the world; only thus can he hope to attain anything on one of these ways.[9]

Gurdjieff believed this was their great disadvantage, because it was in daily life where one’s conditioning occurred, where one’s habits were formed, and where a person’s faults naturally manifest, usually unconsciously, in reaction to the various situations and pressures that arise. That is where greater awareness needed to be applied. By avoiding daily life, one would lose the possibility of studying themselves as they actually are and thereby really transforming their inner condition. By pursuing one of the three ways, one was sacrificing much with very little real prospect of obtaining what could actually be obtained from ordinary life, he believed, and was placing all one’s hope in approaches that were insufficient for the kind of transformation he outlined.[10] The demand placed upon practitioners of the fourth way was not one of blind faith or obedience, upon which the other ways began, but conscious understanding.

A man must do nothing that he does not understand, except as an experiment under the supervision and direction of his teacher. The more a man understands what he is doing, the greater will be the results of his efforts. This is a fundamental principle of the fourth way. The results of work are in proportion to the consciousness of the work…. On the fourth way a man must satisfy himself of the truth of what he is told. And until he is satisfied he must do nothing. [11]

Furthermore, in contrast to the view that sees ordinary life as an impediment, Gurdjieff maintained that in order to progress in the Fourth Way a person had to demonstrate they were reasonably capable of fulfilling normal worldly responsibilities first of all—to be a responsible person with ordinary things—yet at the same time recognise a greater meaning lay beyond the usual aims of ordinary life. This was outlined as a standard that had to be met before admission to groups. The Fourth Way was not for people who wanted to avoid or escape from life’s responsibilities. What had to change was one’s inner attitude to life.

Fourth Way teacher Maurice Nicoll wrote a great deal on these points. He expresses that the Fourth Way is carried out “in the midst of life” which is where the real teaching and development happens. The form of renunciation advocated in the Fourth Way, if you could call it that, is an inner one of “non-identification”—of seeing one’s negative emotions, reactions and manifestations that flare up in reaction to life’s events but not identifying with them. This is where understanding is acquired and self-transformation happens. It is fundamentally a method for “the transformation of daily life” as he put it. The following sample of extracts from his extensive Psychological Commentaries provides a good illustration of this perspective:

“We are not Fakirs holding out our arms year after year; we are not monks living in monasteries; we are not Yogis going to remote schools or sitting and meditating in caves in the Himalayas. We belong to what is called the Fourth Way which is right down in life. So we have to work in the midst of life, surrounded by all the misfortunes of life, and eventually life becomes our teacher—that is to say, we have to practise non-identifying in the midst of the happenings of life; we have to practise self-remembering in the midst of affairs; and we have to notice and separate ourselves from our negative emotions in the midst of all hurts and smarts in daily life.”[12]

“We do not take what happens to us in life in our usual mechanical way. Between the reception of the impressions and the reaction that would mechanically arise, consciousness begins to interfere and this is the whole secret.”[13]

“It is a marvellous thing to realize that one need not take a life-event always in the same way. But for this to begin to take place one has to be able to see the event and at the same time see one’s mechanical reaction to it. When the Work intervenes between these two things, the external event coming in through the senses and the mechanical reaction that would ordinarily take place, when there is this moment of conscious choice which the Work seeks to establish in us, then we begin to understand what the Work is about practically.”[14]

“It is not the events of to-day that happened to you that matter—such as that you lost something or something went wrong or someone forgot you or spoke to you harshly, etc., etc.—but how you reacted to it all—that is, what states of yourself you were in—for it is here that your real life lies and if our inner states were right nothing in the nature of external states could overcome us.”[15]

“The transformation of daily life, that is, of its impact upon us, depends on understanding all that has been taught you about practical work—about self-observation and work on negative states, work on identifying, and so on. It is this that insulates you. When you realize that you need not take a thing or a person in the way you are taking them, you transform something and at the same time you insulate yourself. Self-remembering, non-identifying and not-considering all help to insulate us from the influences of life. Acting consciously at a difficult moment has the same effect.” [16]

“A man aiming at balance knows that every aspect of life is necessary for development. He does not waste his time complaining of life and finding fault with it, because he realizes that life is a school and that is its real meaning, that life is a means and not an end in itself.”[17]

This transformation of daily life stems from what Nicoll describes as the “transformation of the instant,” which is effected within by being more conscious “at this very moment, now.” It is only in the present moment, when one remembers, where this inner work of transformation can be done.

In this connection we must visualize a vertical direction or a ladder extending as it were from below upwards and having many rungs on it. People—all of us—are on one or another of the rungs of this ladder that stands vertically below and above us. This ladder is quite different from time—namely, from past, present and future which we can imagine as a horizontal line. In order to make my meaning clearer, I would like to ask you how you imagine time—that is, the passage of time from the past into the present and into the future. Usually, the kind of mechanical hope that people hold on to is connected with the idea of time—namely, that in the future things will be better, or they themselves will be better, and so on. But this ladder of which we are speaking and which refers to different levels of being has nothing to do with time in this sense. A higher level of being lies immediately above all of us at this very moment. It does not lie in the future of time but in ourselves at this very moment, now. All work on oneself, all personal work which deals with stopping negative emotions, with self-remembering, with not being identified with one’s woes and troubles, with not making accounts, etc., etc., is concerned with a certain action that can take place in oneself at this moment—now—if one tries to be more conscious and remembers what it is we are trying to do in this work. That is to say, the work is about a certain transformation of the instant, of the moment, of the present, through the action of this work.[18]

Thus the fourth way Gurdjieff advocated is based on the idea that life itself provides the teaching, and one must change one’s inner attitude to it, rather than avoid it. One’s inner work, one’s inner growth, occurs in the present moment through perceiving and responding more consciously, which transforms how one lives and one’s level of being. This he considered a more difficult approach to traditional ways of renunciation, but one that could produce faster and better-rounded results.

Walking the Razor’s Edge in the World

There is a poignant scene in the 1984 film The Razor’s Edge which speaks to this idea. It is the second film adaptation of the 1944 novel by W. Somerset Maugham, which tells the story of an American pilot, disillusioned after Word War 1, who goes off to seek knowledge in the East. The story is named after a famous line from the Katha Upanishad. There is much speculation it was inspired, if not entirely based, on a real individual the well-travelled author encountered, as he was known to draw on his extensive experiences for other stories.

Whatever the case, the scene I have in mind is interesting not just because of its relation to what we’re discussing, but because the protagonist Larry Darrell is played by Bill Murray, who himself had studied the Fourth Way.[19] He only agreed to star in the blockbuster hit Ghostbusters, released that same year, if the studio would fund and let him make this film as a passion project. Audiences however were not ready to see Murray, famous for his comedy work, in a serious dramatic role. [20] Commercially and critically the film failed at the time, but some now believe it was underrated.

In this film adaptation, Larry volunteers as an ambulance driver on the frontlines, not a pilot. After the war, he saves up to visit India after finding no answers in his quest for meaning in the West. He meets someone who invites him to a monastery in the Himalayas. There he is eventually instructed to trek to a higher peak, where he sits under a basic shelter, and ends up burning the spiritual books he carried with him to stay warm. Having understood something significant, we next see him back at the monastery, preparing to leave. He tells the head Lama, “Isn’t it true … It’s easy to be a holy man on top of a mountain?” “You are closer than you think,” replies the Lama, “The path to salvation is narrow and as difficult to walk as a razor’s edge.”[21] Larry sets off to re-enter the world, farewelled by the monks with great respect. Once back in the world, he certainly doesn’t have an easy time of it.

Bill Murray as Larry Darrell at a remote monastery in The Razor’s Edge

The parallels to the Fourth Way perspective on seeking transformation in the world cannot be missed. Certainly Murry, who co-wrote the screenplay, had to have been aware of it. The scene is also reminiscent of the final one at the end of the 1979 film, Meetings with Remarkable Men, based on Gurdjieff’s autobiographical book of the same name concerning his own quest for knowledge. The film ends at a remote monastery, where Gurdjieff is told that when he is sufficiently prepared, he must leave and “go back into life” and there contend constantly with “forces which will show you your place.”

While we’re on this subject, it feels appropriate to share this quote from Nicoll, which captures well, in direct modern language, this approach of walking the razor’s edge in the world:

When life becomes one’s teacher, then the highest work is reached. And then you are right in the track of the Fourth Way. But it is difficult—Oh, how difficult!—and requires much and long work on oneself and patient understanding.[22]

We’ll now turn to how this perspective of seeking transformation in life itself, rather than by retreating away from it, shapes how the practice of mindfulness itself is approached in the Fourth Way, and how this approach resonates with some modern approaches to present-moment practice outside the Fourth Way.

The Modern Mindfulness Phenomenon

Mindfulness is the English translation of the Pali word Sati used in Buddhist texts, which means awareness or “to remember”. The modern western understanding of mindfulness is derived mostly, if not exclusively, from Buddhist traditions, where specific mindfulness-based meditation exercises have been formalised in monastic schools. Similar practices can also be found in other Eastern traditions, but mindfulness has probably been more systematised in Buddhism, where it is regarded as one of the seven factors of awakening and a core component of the Buddhist Eightfold Path.[23]

One figure who has done much to introduce and advocate mindfulness to mainstream western audiences, particularly in clinical applications, is Jon Kabat-Zinn, who created the “Mindfulness-based stress reduction” method, or MBSR, a secular eight-week training course. His books Full Catastrophe Living (1990) and Wherever You Go, There You Are: Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life (1994) were among the early wave of mindfulness books in the 1990s that became bestsellers amidst a groundswell of interest in the subject. As well as including more formal meditation exercises, usually categorised as “formal practice,” the more informal practice of mindfulness in daily life is also encouraged by Kabat-Zinn. Due to their popularity and influence, these texts provide a good example of formative perspectives of the wider mindfulness movement. It is worthwhile looking at a sample of extracts from them, to see how certain themes are addressed:

“Simply put, mindfulness is moment-to-moment non-judgmental awareness. It is cultivated by purposefully paying attention to things we ordinarily never give a moment’s thought to.”[24]

“All of us have the capacity to be mindful. All it involves is cultivating our ability to pay attention in the present moment…. We routinely and unknowingly waste enormous amounts of energy reacting automatically and unconsciously to the outside world and to our own inner experiences. Cultivating mindfulness means learning to tap and focus our own wasted energies…. At the same time it makes it easier for us to see with greater clarity the way we actually live and therefore how to make changes that enhance our health and the quality of our life.”[25]

“A diminished awareness of the present moment inevitably creates other problems for us as well through our unconscious and automatic actions and behaviors, often driven by deepseated fears and insecurities.”[26]

“We practice mindfulness by remembering to be present in all our waking moments. We can practice taking out the garbage mindfully, eating mindfully, driving mindfully. We can practice navigating through all the ups and downs we encounter, the storms of the mind and the storms of our bodies, the storms of the outer life and of the inner life.”[27]

What I find noteworthy about these views are the commonalities they share, in at least some important ways, with notions expressed earlier in The Fourth Way—which as noted, emphasises taking spiritual practice into everyday life. Charles Tart observes, for instance, that Gurdjieff’s work was specifically intended to “produce … mindfulness in everyday life situations” in order to study and overcome “automatized, unconscious reactions” occurring within them.

“G.I. Gurdjieff was one of the first people to try to adapt Eastern spiritual practices to forms more suitable and effective for contemporary westerners…. His main theme was that man was “asleep” … living a life with perception, thought and feeling badly distorted by automatized beliefs and emotions. “Waking up” to higher levels of consciousness was the only worthwhile goal. Gurdjieff’s main practices, self-observation and self-remembering, were intended to produce increasing degrees of insight and mindfulness in everyday life situations.”[28]

“It is the shift in attitude that you can make [towards daily life] that is most valuable. You begin to recognize that you do not know your own psychology; that you are caught up in automatized, unconscious reactions that you do not understand and that cause you trouble. You come to realize that you must understand what is going on in you before you can effectively do something about it, and that you need to engage in self-study, self-remembering and self-observation.”[29]

An additional reason cited to overcome “automatized, unconscious reactions” in The Fourth Way is to prevent the wastage of energy this produces. By perceiving and responding to the moment more consciously, it’s said that energy is preserved and redirected towards one’s inner development. A similar point about conserving energy, quoted earlier, is made by Kabbat-Zinn.

Another point of agreement between Fourth Way and modern mindfulness literature is the idea of bringing awareness to what is happening within oneself without falling into negative thought patterns of judgment or criticism, but to “simply see” or observe “what is going on in yourself” with awareness, as Nicoll explains below:

You do not observe yourself in order to criticise yourself. If you do so it will at once stop self-observation …. When self-observation begins to accompany you, you will notice that it is not critical: it is simply a slight degree of consciousness. It is not a critical consciousness, a judging consciousness, but an awareness. Through this awareness you simply see more. You recognize, let us say, something that you said before, or you see that you are doing something that you did before, or that you are behaving like this or like that, or having these thoughts that you had before or these feelings that you had before. This awareness does not accuse you: it says nothing but merely shews you what is going on in yourself.[30]

The body scanning/sensing morning exercise

There is also a more formal exercise of “directed attention” in the Fourth Way that involves “putting consciousness into every part of the body” [31] which comes close to being a formal mediation practice as they are commonly understood. It was never described in writing by Gurdjieff himself, but apparently only conveyed by him verbally. The exercise was only ever hinted at by Nicoll and Ouspensky in their writings—the latter calls it a “circular sensation” exercise which, in his description, is done lying down on one’s back.[32] It involves relaxing and directing one’s attention to the different parts of one’s body, focusing attention on one part and feeling the sensations there before shifting to the next, until one has cycled through the whole body. Then one extends their perception to sense the body as a whole.[33] [34]

Tart states it is known as “the morning exercise” in Fourth Way groups, and describes it as “a body-scanning exercise … somewhat like the sweeping method of one contemporary form of vipassana [Buddhist meditation].” [35] It also seems reminiscent of the “Body-Scan Technique” used in MBSR (Kabbat-Zinn does make reference to having experience with contemporary vipassana/insight meditation techniques) and is not that dissimilar to the “inner body awareness” exercise later described by Eckhart Tolle (and before him by Barry Long) either. [36] In any case, the Fourth Way morning exercise is ideally done shortly after rising, before one begins daily activities, in order “to start the day off with consciousness of what is happening in your body and to remind you that you intend to be mindful through the day.” It may be done seated. The practice is supposed to then lead “directly into self-observation and self-remembering” upon completion, for which “washing, dressing, eating—all are to be taken as occasions for.”[37]

Kenneth Walker, a close friend Maurice Nicoll, was like him a pupil of Ouspensky and, for a time, Gurdjieff too. In his book A Study of Gurdjieff’s Teaching he notes that Gurdjieff tended to emphasise that: “The first step to self-remembering was to come back from our mind-wandering into our bodies and to become sensible of these bodies.” He relates how Gurdjieff taught this “body-sensing” exercise to him directly, which Walker found “particularly useful as a preparation for self-remembering.” He writes that Gurdjieff:

“… taught us a number of exercises in muscle-relaxing and in what he called ‘body-sensing’, exercises which were and still are of the greatest value to us. We were told to direct our attention in a predetermined order to various sets of muscles, for example, those of the right arm, the right leg, the left leg and so on, relaxing them more and more as we come round to them again; until we have attained what we feel to be the utmost relaxation possible for us. Whilst we were doing this we had at the same time to ‘sense’ that particular area of the body; in other words, to become aware of it. We all know, of course, that we possess limbs, a head and a body, but in ordinary circumstances we do not feel or sense them. But with practice the attention can be thrown on to any part of the body desired, the muscles in that particular area relaxed, and sensation from that region evoked. At the word of inner command the right ear is ‘sensed’, then the left ear, the nose, the top of the head, the right arm, right hand and so on, until a ‘sensation’ tour has been made of the whole body.”

Whether coincidental, a case of convergent evolution, or otherwise, attempts to adapt Buddhist mindfulness to modern western lifestyles are certainly reminiscent of approaches introduced by Gurdjieff earlier, in at least certain respects. Yet despite these similarities, Gurdjieff and the Fourth Way do not feature prominently in modern expositions of mindfulness adapted for contemporary life, if mentioned at all, nor does there seem to be widespread awareness of how the Fourth Way shares parallels with these latter approaches, regardless of whatever differences exist. Admittedly, I am not well versed enough to make sweeping generalisations—and there are tens of thousands of books for sale about mindfulness according to Amazon search results—but my impression from reading prominent titles as well as articles about the modern mindfulness phenomenon, is that Fourth Way precedents that prefigure it do not seem to be “on the radar” in prominent mainstream sources.

There are exceptions of course. Charles Tart is a notable one, and I am aware of others, such as Jack Kornfield, who has referenced Gurdjieff’s perspective when discussing mindfulness.[38] However Tart’s book Living the Mindful Life: A Handbook for Living in the Present Moment, which I’ve quoted from a number of times already, is the only text I’ve encountered which deals with the interface between Gurdjieff’s approach and Buddhist-based mindfulness practice directly and in depth. Within this book, Fourth Way and traditional Buddhist approaches to mindfulness are discussed and sometimes contrasted.

Living the Mindful Life was published in 1994, but is based on workshops Tart delivered in 1991 in a traditional Buddhist centre, where Fourth Way methods were used to teach the application of mindfulness to daily life. When comparing these two traditions, Tart notes that in his experience, traditional Buddhism places far more emphasis on formal practice, such as seated meditation, with little actual practical guidance of how to bring the state of mindfulness into daily life, whereas the opposite is the case in the Fourth Way. Each tradition incorporates both aspects, he acknowledges, but the emphasis is reversed.

I have said that Gurdjieff’s path is primarily a matter of mindfulness in everyday life. He taught, to the best of my knowledge, almost nothing in the way of formal, sitting meditation practices as we would ordinarily categorise them—although they were introduced to some extent by some of his students later. His theory is that the place where you create all your trouble is ordinary life, and so that is both the place where you need mindfulness the most and the best possible place to learn it.

I personally find Gurdjieff’s practices for creating mindfulness in daily life much more practical and successful than Buddhist ones. In my (hopefully, too limited) acquaintance with several Buddhist systems, they always stress that you should be mindful in ordinary life, not just in meditation, but in practice, almost all the emphasis is on formal meditation, and there are very few, if any, practical techniques given for bringing this mindfulness into everyday life. [39]

Tart suggests this occurs because: “Historically, Buddhism in the East has, by and large, been nurtured and institutionalized as a monastic culture.” This meant “Life was one big retreat for core practitioners” and “monastic life was ordinary life for the core practitioners.” [40] This, in his view, made traditional Buddhist systems less adapted towards offering guidance for contemporary practitioners in the West seeking to extend mindfulness beyond retreat settings into ordinary life. His workshop was provided in part to compensate for this.

The same issue is not so pronounced in modern mindfulness modalities deliberately separated from a religious context and secularised. Nevertheless, to my mind formal practice still seems to be given primary emphasis in courses such as MBSR, yet there is undoubtedly a significant shift towards extending mindfulness into the ordinary activities of daily life. This is often presented and discussed explicitly as “mindfulness in daily life”—a core object, as already noted, which the Gurdjieff work embodied.

Thus it’s fair to say that Fourth Way approaches to present-moment awareness are very much in sync with contemporary sources on mindfulness, in at least some respects. In both we find an emphasis on bringing greater mindfulness or awareness into the practicalities of everyday life, rather than, for instance, the pursuit of specialised lifestyles in monastic settings as is typical of traditional Buddhism. And some corresponding points are expressed about how and why this should be done.

There is an important difference worth mentioning, however. As noted, in secular mindfulness modalities, mindfulness is pursued in isolation from traditional roots, outside of a spiritual teaching, religion or creed. This was purposefully done to make the application and benefits of mindfulness more universal, irrespective of anyone’s religious orientations or lack thereof. It was also done, as Kabat-Zinn makes clear, to make mindfulness more acceptable in clinical settings and to the scientific world, so it could be utilised, recognised and studied as a form of therapy and treatment.[41] To this end, he certainly succeeded, as the health and psychological benefits of mindfulness are now widely appreciated scientifically, and it is utilised in many non-religious contexts.

In contrast, the Fourth Way was introduced as a kind of spiritual school in which exercises and psychological teachings were taught alongside a complex cosmology they were integrated with. Similar to Buddhism and other religious orders, awakening and self-transformation were the ultimate transcendental goal, and discipline and commitment were required to participate, with rules to be followed. It was just that that, in contrast to traditional monastic schools of east or west, it was organised to be applicable for practitioners leading lives in the world rather than away from it.[42]

The decoupling of mindfulness from its religious origins in the modern mindfulness movement has undoubtedly brought many health and psychological benefits to people who otherwise would not have encountered the practice. It has not been without its critics, however. As mindfulness increased in popularity and became a popular catchword, it also became something of a commercial bandwagon that many jumped upon, giving rise to the critical label “Mc-Mindfulness” for some manifestations. [43] Nevertheless, it is within the New Age movement where I think that some of the most conspicuously commercial forms of present-moment oriented practice can be found.

The New Age Now: The Rise of Eckhart Tolle

Perhaps the most commercially successful writer on present-moment awareness is New Age celebrity author Eckhart Tolle. His books The Power of Now: A Guide to Enlightenment (1997) and A New Earth: Awakening to your Life’s Purpose (2005) are worldwide bestsellers and have been translated into more than 50 languages. Their stratospheric sales began a few years after their initial publication, however, after each was promoted by TV personality Oprah Winfrey. The Power of Now featured in “O Magazine” in 2000, and A New Earth was featured in her book club in 2008, after which it “immediately hit the top of the best-seller lists.”[44]

A New Earth was further boosted that year when, in addition to her book club promotion, Winfrey and Tolle co-presented a 10-week webinar series live over the internet, with each week’s presentation focused on a corresponding chapter from the book. The video broadcasts, joined by millions across the globe, were backed by major corporate sponsors and featured live audience questions called-in over Skype. Web forums were also provided for participants to discuss the material outside the webinars. This was an unprecedented collaboration for Winfrey at the time, which she described as “the most exciting thing I’ve ever done.”[45] In the wake of these events, “by 2009, total sales of The Power of Now and A New Earth in North America had been estimated at three million and five million copies respectively.”[46] Ten years later, total global sales figures were placed at 12 and 15 million copies apiece. [47]

Eckhart Tolle in 2010

In Tolle’s first book The Power of Now, we find calls to place one’s attention in the present moment with phraseology at times reminiscent of the mindfulness literature popular in the period. For example, Tolle advocates, “present-moment awareness,” the benefits of conscious breathing, practicing “acceptance” but not resignation in difficult situations, and allowing the moment “to be.” Such themes are familiar in mindfulness territory. To give some examples of commonalities: while Kabat-Zinn speaks of “present-moment awareness”[48] and tells us “you are not your thoughts,”[49] Tolle also speaks of “present-moment awareness”[50] and affirms “you are not your mind.”[51] While the former advises we should “allow this moment to be exactly as it is”[52] Tolle tells us to “allow the present moment to be.”[53] And while Kabat-Zinn advocates “acceptance of the present moment” but not “resignation in the face of what is happening,”[54] Tolle advocates “Acceptance of the Now” but not “Resignation” in the face of “an undesirable or unpleasant life situation.”[55] And there are, of course, requisite calls in both sources to undertake ordinary daily activities with awareness—which, as we have noted, is an approach prefigured in the Fourth Way.

Kabat-Zinn evidently approved of Tolle’s books’ content and message, listing The Power of Now among recommended reading material in the 15th anniversary reprint of Full Catastrophe Living, under “Applications of Mindfulness and Other Books on Meditation.”[56]

But beyond these obvious parallels with the mindfulness movement, there are also signs Tolle may have been directly influenced by Fourth Way perspectives. Unlike most modern mindfulness literature, Tolle’s work is almost exclusively about being in the present moment in daily life—there is comparatively very little emphasis on formal meditation practice. This is one of a number of parallels shared with the Fourth Way approach.

I noted in a previous article that Tolle’s phrase “The Power of Now” is reminiscent of Maurice Nicoll’s earlier phrase “the creation of now” which carries a similar meaning—to be conscious in the present. “Creation of Now” was used as a chapter title in Nicoll’s work Living Time; and the following passage comes from this book:

What raises the level of consciousness and opens us to a different aspect of the WORLD is the creation of now. The time-man knows only state, hurrying from one into another. Now is vertical to this, and belongs to the scale of degrees. In now we get above state. Inner space is changed, enlarged…. The great negations that belong to the illusion of passing-time begin to leave us, and all the life begins to enter now. [57]

The same can be said for Tolle’s reference to horizontal and vertical dimensions of time and the timeless, only mentioned briefly in The Power of Now and A New Earth, but discussed further elsewhere, notably the seventh presentation he made with Winfrey in their 10-week webinar series. In a manner reminiscent of Nicoll’s expositions, Tolle expresses the notion that the horizontal and vertical dimensions intersect in the present moment, can be represented by the Christian cross, and that one accesses the timeless vertical dimension by being conscious in the present. The following extract is just one sample of this idea being expressed in Nicoll’s work (see more examples of similarities here):

The diagram of the Cross as given represents a single moment in a man’s life. In this single moment the vertical line is cut across by the horizontal line of Time.

The point of intersection of the vertical with the horizontal line is now. But this point only becomes now in its full meaning if a man is conscious. When a man is identified there is no now for him. If he is asleep in Time, being hurried on from past to future, identified with everything, there is no now in his life. There is not even a present moment. On the contrary, everything is running, everything is changing, everything is turning into something else; and even the moment so looked-forward to, so eagerly anticipated, when it comes is already in the past.

It is only this feeling of the existence and meaning of the direction represented by the vertical line that gives a man a sense of now. This feeling is sometimes called the feeling of Eternity. It is the beginning of the feeling of real ‘I’, for real ‘I’ stands above us, not ahead of us in Time.[58]

As a side note, it is interesting to observe that Nicoll quoted the medieval mystic Meister Eckhart in his “Creation of Now” chapter in Living Time, and the same figure is the source of Tolle’s adopted first name, which was changed to Eckhart before he published his first book The Power of Now.

Maurice Nicoll in 1953

I recently came across a section in Tart’s Living the Mindful Life, which reminded me a great deal of an extract in The Power of Now. Tolle’s book appeared a few years after Tart’s, but I had read Tolle’s formerly. Here are the relevant parts side-by-side:

One response to the deadness of everyday life, to the shallowness to living in samsara, in consensus trance, is to seek out danger…. In certain dangerous sports, for example, like skiing to the limit or auto racing, you must be present to the physical world. If your attention lapses for two-tenths of a second, you may maim or kill yourself. You are forced to be present. As another example, a lot of World War II Veterans, when interviewed later, said that being in combat was the most alive, most real time in their lives…. The fact that this kind of danger can force us to be more present, and so feel more vital and alive, is one of the problems with trying to stop war…. [However by using mindfulness techniques] you can become more alive without having to put yourself and everyone else in mortal danger.

~ Charles T. Tart, Living the Mindful Life: A Guidebook to the Present Moment (1994)[59]

The reason why some people love to engage in dangerous activities, such as mountain climbing, car racing, and so on, although they may not be aware of it, is that it forces them into the Now – that intensely alive state that is free of time, free of problems, free of thinking, free of the burden of the personality. Slipping away from the present moment even for a second may mean death. Unfortunately, they come to depend on a particular activity to be in that state. But you don’t need to climb the north face of the Eiger. You can enter that state now.

~ Eckhart Tolle – The Power of Now: A Guide to Enlightenment (1997) [60]

I was struck by the common constellation of points, examples and keywords assembled to communicate essentially the same argument:

- Physically dangerous activities—both cite motor racing—are often pursued because they force one into the now or present;

- Not being present even for a moment would kill participants otherwise;

- The inner state produced makes people feel alive even if they don’t understand the deeper reason;

- It is ultimately unnecessary, however, to seek danger to be present in the now.

To my judgement, these commonalities suggest the likelihood Tolle was probably familiar with Tart’s Mindful Life and possibly influenced by it, at least on this particular point. And if he was familiar with that book, he would in turn be familiar with the Fourth Way more broadly and modern perspectives on Buddhist mindfulness, as Tart’s book discusses both and provides something of a crossover perspective on them.

But even if we were to discount those passages, there are many other correspondences with Fourth Way perspectives in Tolle’s work, especially with Maurice Nicoll’s work in particular. I believe this may be the case because he did more than any of Gurdjieff’s students, in my opinion, to describe the practical psychological aspects of that teaching—particularly self-observation—in accessible literature which has been appreciated beyond Fourth Way groups.

I’ve mentioned some similarities already, but there are more that could be discussed. One area I’ll briefly touch on is the similar phraseology around how self-observation is presented. For example, Maurice Nicoll describes self-observation as an “act of attention directed inwards”[61] and elsewhere states “self-observation is inner attention”.[62] When explaining “self-observation” Tolle similarly advises to “direct your attention inward”[63] and in another place writes: “just watch. Focus your attention within.”[64] Both authors explain that this attention is used to observe one’s own thoughts and emotions without identifying with them. Each specifically refers to the “power of self-observation” and claims that this can be developed or sharpened through greater use.[65] [66] They also describe “the light of consciousness” being present and active through observation and having psychologically transformative effects, such as reducing certain negative unconscious aspects within—if these are brought into the light of consciousness through direct observation.[67] [68]

As I noted in my last article, “the light of consciousness” is a phrase Nicoll appears to have repurposed from Jungian psychology, in which he was trained. It was one of his idiosyncrasies to refer to “the light of consciousness” repeatedly in his writing and suggest that it operated through the practice of self-observation specifically, rather than by other methods.[69] It is interesting to see the same phrase appear with similar applications in Tolle’s work.

I’m now stepping into a much bigger topic, however. I don’t wish to become bogged down in the many details I could go into; I’ve cited just some examples only to substantiate my premise that Fourth Way literature and methods carry a wider influence than is commonly recognised. It is also for this reason that I look at Tolle’s work, as it represents the pinnacle of commercial success and cultural influence among modern—probably any—authors addressing these ideas. It is relevant then to focus here, because it shows how far the influence I’m pointing to may have travelled.

Just to underscore my point about Tolle’s prominence, note that he often ranks in the top five of the Watkins Spiritual 100 annual rankings of the world’s most spiritually influential living people. In the debut 2011 list, he ranked first as “the most spiritually influential person in the world,” as his online biography duly describes,[70] relegating even the Dalai Lama to second place, believe it or not.[71] The next year he’d fallen to second place, with the Dalia Lama taking the lead,[72] and again claimed the second spot in 2014—ahead of the Pope, who ranked third.[73] In 2015 he ranked third behind these two religious leaders.[74] From 2016-21 he has consistently ranked fourth.[75] Irrespective of whatever subjective bias may be present in the ranking process, it’s certainly indicative of Tolle’s enduring fame and popularity. This incredible popularity is why it is instructive to look at Tolle’s work in particular.

Eckhart Tolle (left) with the Dalai Lama at the Vancouver Peace Summit, September 2009

However, I don’t want to go too far down the rabbit hole. My intention has been to highlight some evidence that a broader Fourth Way influence exists in our culture. Having done so, I should now point out an important feature that distinguishes Tolle’s work from both the Fourth Way and other mindfulness literature—whether secular or Buddhist orientated.

Immediatist Enlightenment

Arthur Versluis, a Professor of Religious Studies, has described a rising phenomenon in modern spiritual literature, although by no means exclusive to it. He calls it “immediatism.” It is a perspective which suggests near-instant awakening or enlightenment is possible. He describes it as follows:

Immediatism refers to a religious assertion of spontaneous, direct, unmediated spiritual insight into reality (typically with little or no prior training), which some term “enlightenment.” Strictly speaking, immediatism refers to a “pathless path” to religious enlightenment—the immediatist says “away with all ritual and practices!” and claims that direct spiritual enlightenment or awakening is possible at once. Immediatism is, in other words, a claim that one can achieve enlightenment or spiritual illumination spontaneously, without any particular means, often without meditation or years of guided praxis. [76]

In his book American Gurus: From Transcendentalism to New Age Religion, from where the above quote comes, Versluis points to Tolle as a prominent example of the immediatist phenomenon. Tolle is by no means alone, he points out, but having been “catapulted to ‘bestseller-dom’ by the phenomenally popular daytime talk show host Oprah Winfrey’s enthusiastic endorsement of his work,” he views Tolle as the most prominent exemplar of this growing phenomenon once “inconceivable” in mainstream American society but now becoming “nearly commonplace.”[77]

Tolle’s immediatist orientations are most evident in his own self-realisation claims. He suggests his self-realisation happened instantly one evening when he was grappling with long-term anxiety and suicidal depression. He had a suicidal thought, and then observed and experienced a sudden moment of detachment, or disidentification, from this negative thought or self. He realised this was not who he really was. He then fell asleep and woke up blissful, by his account, feeling peace without end ever since. However, he states that he did not understand what had happened for several years.

I knew, of course, that something profoundly significant had happened to me, but I didn’t understand it at all. It wasn’t until several years later, after I had read spiritual texts and spent time with spiritual teachers, that I realized that what everybody was looking for had already happened to me.[78]

It took “about ten years” before the transformation was fully understood and “integrated” into his life and personality, as he describes it.[79] [80] [81] During these years of integration, before his teaching career began, he “would retreat into the University of London Library nearby and pore over esoteric books.”[82]

When asked in 2000 how he knew his realisation was true, and that the same could also be realised by others (his first book is subtitled “A Guide to Enlightenment” after all) he provided this answer:

The certainty is complete. There is no need for confirmation from any external source. The realization of peace is so deep that even if I met the Buddha and the Buddha said you are wrong, I would say, “Oh, isn’t that interesting, even the Buddha can be wrong.” [Laughter] So there is just no question about it. And I have seen it in so many situations when there would have been reaction in a “normal state of consciousness”—challenging situations. It never goes away. It’s always there. The intensity of that peace or stillness, that can vary, but it’s always there.[83]

These kinds of claims are not typically found in the more grounded secular mindfulness movement, nor the Buddhism it derives from, and certainly not in the Fourth Way. The mindfulness movement does not position itself as a guide to enlightenment—it is more focused on health, wellness and stress reduction. Buddhism does not suggest enlightenment is quick either—it was not said to be for Buddha—nor is it said to be reached by practicing mindfulness alone; this forms part of a whole discipline that also includes “right effort” for example. And as for the Fourth Way, it stresses “work on oneself” involving prolonged effort and struggle, and this prolonged process is said to be necessary to obtain lasting transformation.

For instance, Nicoll writes that “the object of the Work is to stir up a struggle in us.” This struggle is actually required to confront and overcome everything false and negative in oneself, and is instigated by self-observation.[84] This “inner struggle” produces a friction which Gurdjieff suggests will “create a fire which will gradually transform” a person’s “inner world.”[85] By observing oneself and living consciously a person is “breaking new ground in his own Being,” Nicoll indicates.[86] A smooth and easy inner life, he suggests, may not be a good sign but can mean one is not “going against” themselves[87]—not confronting the falsity, illusions and negativity hidden within, but leaving it undisturbed.

To make the effort to work on yourself you must actually feel something is wrong with you. It usually takes years and years before a person can even begin to see this with any conviction. The Work has to pass through layer after layer of pride, vanity, ignorance, self-complacency, self-indulgence, self-love, self-merit, and so on. Yet it can penetrate eventually.[88]

When Nicoll writes, “Great knowledge demands great sacrifice and a long struggle with oneself,”[89] he is voicing a central principle of the Fourth Way—and arguably one found in many spiritual traditions. In contrast, there is little if any talk of work, struggle or sacrifice in Tolle’s major works—in fact he pointedly speaks against having to struggle or work for inner transformation. He suggests that inner joy and peace are not something that “you need to work hard for or struggle to attain”.[90] He further holds that people should “offer no resistance to life” and things will “come to you with no struggle or effort on your part”[91] when you have this state. “As soon as you honor the present moment, all unhappiness and struggle dissolve, and life begins to flow with joy and ease,” writes Tolle.[92] He shows a particular antipathy towards “the word work” suggesting it will “disappear from our vocabulary” as “more humans awaken.”[93]

Yet if Tolle seems to suggest that self-realisation can, at least in some cases, be sudden and spontaneous, he does not outline clearly how this may be obtained for others. In fact, he suggests it is unlikely to happen that way for most. Tolle actually writes in a few places that a “sudden, dramatic, and seemingly irreversible awakening” that happens “radically, once and for all” occurs only in “rare cases” with “rare beings,” whereas “for most people it is not an event but a process they undergo” and they “have to work at it.”[94] [95] It seems evident, from his own account, that he sees himself in the “rare” category. But his tacit admission—and you have to search his words closely for it—seems to be that there is a process of “work” most ordinary folk have to go through. But he seems reluctant to emphasise this point, and reticent to outline what that process of work comprises in too much detail.

Despite his immediatist claims about his own awakening, Tolle does not teach an obvious method to replicate it. The methodology he actually teaches is present-moment awareness involving self-observation, and when outlining this practice he even suggests it takes time to “dissolve” any entrenched emotional pain or negativity observed, even if one has stopped identifying with it. “In most cases,” he states outright in one place, this “does not dissolve immediately.”[96] In another instance, he likens the emotional negativity built up within to “a spinning wheel that will keep turning for a while even when it is no longer being propelled.”[97] It takes time to lose momentum, he indicates, and one must persistently “stay present, stay conscious” and “ever-alert” to it if one is to ultimately be free of it eventually.[98] He does not call this process work as such but it certainly sounds more akin to the Fourth Way approach,which stresses self-observation must be continuous and ongoing to be effective.[99] [100] Nevertheless, his message is muddled because he also writes: “If you were conscious, that is to say totally present in the Now, all negativity would dissolve almost instantly,” and “In the Now, in the absence of time, all your problems dissolve.” [101] The latter kinds of messages tend to be more emphasised in his work.

There is thus a contradiction in Tolle’s work then. He indicates enlightenment can be sudden, but does not actually teach how to have or replicate his purported immediatist experience (if we accept it is even possible). And he stresses work and struggle are unnecessary, and apparently hopes the word “work” will die out—but also seems to admit that it’s necessary for most, yet declines to elaborate too much further on what it entails. That seems to be a fairly large oversight in any purported guide to enlightenment. In my personal opinion, Tolle’s hesitancy to acknowledge more plainly that the process of confronting unconsciousness within is not quick and easy—and certainly not a continual process of joy and ease—will undoubtedly cause confusion or disappointment for some. His explanations leave someone ill-prepared for the difficulties inevitably faced when sincere self-observation is carried out. These are glossed over too much.

Tolle’s immediatist leanings certainly do not find precedence in Fourth Way or mindfulness literature, Buddhist or otherwise. They are more akin to perspectives found in some strains of Neo-Advaita, a modern western take on traditional Hindu Advaita Vedanta that draws heavily, without official sanction, from the teachings of 20th century Indian guru Sri Ramana Mahareshi, and others expressing similar views such as Sri Nisargadatta Maharaj. While certainly not teaching Neo-Advaita per se, Tolle has spoken very highly of the above figures recognised by this movement. He has also suggested his work is “at One” with Ramana Mahareshi’s as well as Jiddu Krishnamurti’s—another figure who suggested there is no path to truth.[102] Perhaps this may explain the contradiction in Tolle’s work on this issue: he expresses beliefs somewhat concordant with Neo-Advaita, but presents them alongside a methodology of self-observation more akin to Fourth Way and mindfulness approaches, which derive from systems affirming that consistent practice is necessary.

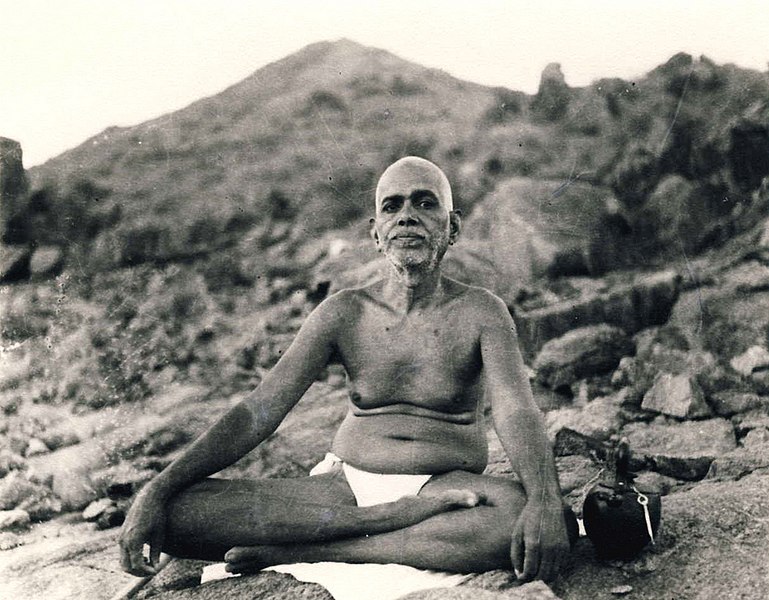

Ramana Maharshi on the mountainside where he lived most of his life, with few possessions.

It should be noted, however, that Neo-Advaita has come under criticism by proponents of more traditional Advaita, which they claim it has distorted. And some argue Ramana’s message has been distorted by this movement also. For example, Ramana did not actually insist no effort was required to reach enlightenment, at least for most people, but stated: “Enlightenment is not your birthright. Those who succeed do so only through proper effort.”[103] And the idea, prominent within Neo Advaita, that self-realisation can be sought without dedicated practice or discipline of some kind, or without making serious changes to one’s life, is particularly criticised by traditionalists.[104] Vedic teacher and writer Dr David Frawley puts it this way:

In much of neo-Advaita, the idea of prerequisites on the part of the student or the teacher is not discussed. Speaking to general audiences in the West, some neo-Advaitic teachers give the impression that one can practice Advaita along with an affluent life-style and little modification of one’s personal behavior. This is part of the trend of modern yogic teachings in the West that avoid any reference to asceticism or tapas [spiritual exercises and discipline] as part of practice, which are not popular ideas in this materialistic age.[105]

Monetising the Moment

Critics of Neo Advaita also point out that Sri Ramana Mahareshi and Sri Nisargadatta Maharaj both taught for free, but the overt business-like manner of some western expressions of this movement are at odds with this approach. Indeed a consumerist-based approach to spirituality is at odds with most traditional forms of spiritual teaching more broadly. On this front, Tolle also finds some commonality with others categorised in the Neo-Advaita movement. I mentioned earlier that Tolle provided perhaps the most conspicuously commercial forms of present-moment oriented practice, and I do not state that simply because of high book sales. To give an idea of what I mean, I’ll quote from the Christopher Titmuss Dharma Blog:

In October 2013, Eckhart and [his wife] Kim Eng gave a five day retreat in Italy. His website said the retreat cost $995.00. I took a second breath when I saw the price for the retreat. And that was before I noticed the dreaded asterisk. On the asterisk below, it read:

*Tuition price only. Accommodations and meals package is additional.

Eckhart and Kim Eng charged $995.00 (£600, €725) for their tuition of participants for their five day retreat, plus sales of books, DVDs, calendars and so on. You do not have to be a rocket scientist to work out how much money they receive if 500 attended. They could have made for themselves about half a million dollars in five days.

Participants booked through Eckhart Teachings to pay to stay in nearby hotels, ranging from $500 to $1000 for the five nights – a walking distance to the huge conference hall to listen to Eckhart. If participants make their own housing arrangements, then they pay Eckhart Teachings, a “commuter fee of $295 including meals and yoga mat.” [106]

According to events promoted on Tolle’s website, this pattern continues. Tickets to a two-day retreat advertised for November 2021 in Hawaii called “The Depths of Being” are selling for $1497 USD. We are told this “covers tuition only” and lodging is paid separately (not to mention airfares). That certainly is not a model of in-person teaching delivery accessible to most in the world. Nevertheless, while retreats like this may be exclusive and out of reach for many, Tolle’s books have undoubtedly reached a mass audience, spreading the ideas within them on a global scale.

Closing Comments

In attempting to trace how the Fourth Way has had a much deeper influence than is generally recognised I have touched upon many other interesting topics along the way, some that I might revisit later. But I want to come back to my central point now. The idea that self-development is pursued primarily in the sphere of ordinary life, by bringing awareness to one’s daily actions and inner states in the present moment, was a hallmark of the early 20th century Fourth Way movement. It is worth considering just how novel and indeed revolutionary that approach was at the time, at least in mainstream Western society.

While some New Age and secular mindfulness authors today certainly do draw upon older traditions, such Buddhist or Hindu sources, the emphasis on pursuing greater awareness and insight primarily in the sphere of ordinary contemporary life owes much I believe to the trail blazed earlier by Gurdjieff and the Fourth Way tradition he instigated. Early teachers of that tradition such as Ouspensky and, most of all Maurice Nicoll, did much to communicate and explain, in accessible literature, an approach to present-moment practice in daily life, diffusing it to a wider audience beyond the Fourth Way. In time these ideas became pervasive. Many elements of the practical and insightful approach they conveyed have since been popularised. But it was they who first laid the groundwork which set in motion a revolution of the present moment, awakening people to the benefits of a shift in consciousness that can happen now in the moment—a transformation of the instant—that Nicoll once called “the creation of now”. Their influence remains palpable today, even if much was arguably lost in translation in the process of diffusion.

In my previous blog I argued that Maurice Nicoll has had a wider influence than is commonly recognised, extending far beyond The Fourth Way. Here I’ve elaborated on that claim by highlighting some prominent examples. I’ll discuss this premise in more detail in future blogs.

References

Last updated 27 September 2022

Return to top

Leave a Reply