Maurice Nicoll and Eckhart Tolle describe three distinct aspects that shape our core sense of identity. “Essence” is our true eternal self; “personality” is a transient but necessary worldly self; then there’s an entirely false self—a fictitious self-image we strongly identify with that’s purely detrimental. When we say “I” it could mean any one or a combination of these—but quite often the latter, they suggest. This article continues my comparative analysis of parallel themes in their work. Here, I examine how they give similar definitions, meaning and significance to these three aspects of self-identity in their discourses on self-knowledge and inner transformation. I also highlight some important ways their views differ.

What do we mean when we say “I”? Much of esoteric philosophy and mysticism turns on this existential question. Answers may be nested in broad cosmological frameworks, or, the way to experience and realise the truth directly—by some practice or inner work to transcend or transform one’s ordinary state—may be emphasised. A spiritual or esoteric teaching can, and ideally should I think, provide both.[1]

When G.I. Gurdjieff’s “fourth way” teaching was added to the western esoteric stream in the early 20th century, a new vernacular, conceptual framework and practices were introduced that continue to shape and influence how some people approach self-knowledge and self-development today. While this is to be expected within the Fourth Way tradition that grew out of this teaching, the influence also extends much further beyond that sphere.

Their focus is on bringing essence, our real and deeper self, to the fore, making personality subordinate to it, and dissolving the false egotistical self entirely.

At this blog, I’ve been exploring Fourth Way influence on popular, modern forms of New Age spirituality, [2] focusing on correspondences in the work of bestselling author Eckhart Tolle and little-known Fourth Way teacher Maurice Nicoll. [3] The latter wrote extensively on matters Tolle echoes in many respects. However, in contrast to Tolle, Nicoll is a niche, esoteric author, and the correspondences I mentioned are generally dispersed throughout his vast, five-volume tome, Psychological Commentaries on the Teaching of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky. Nicoll’s vast corpus, published in the early 50s, covers a much broader scope than Tolle’s more accessible bestsellers. So the similarities must be carefully sifted out to be identified. That’s a large part of what I’ve been doing here.

In my comparative analysis, I’ve already shown how Nicoll and Tolle approach practical self-knowledge in many analogous ways, particularly in how they describe self-observation. This practice represents an experiential approach to self-knowledge. One is not told to believe in self-observation or its effects; rather, it’s posited as a means to see and understand oneself directly in daily life, and bring about inner transformation.

Having explored this practical self-knowledge method, I turn again to the models of the psyche they present and, to a certain extent, their cosmologies. [4] How do they address the question of who we are conceptually? They perhaps emphasise this more theoretical component less; and Tolle’s conceptual framework is far more vague and nebulous by comparison; he does not teach a defined “system” like Nicoll. Nevertheless, this side of their work holds an important place for both: framing what can be experienced through inner practice as well as mapping possibilities beyond that sphere, such as what happens after death.

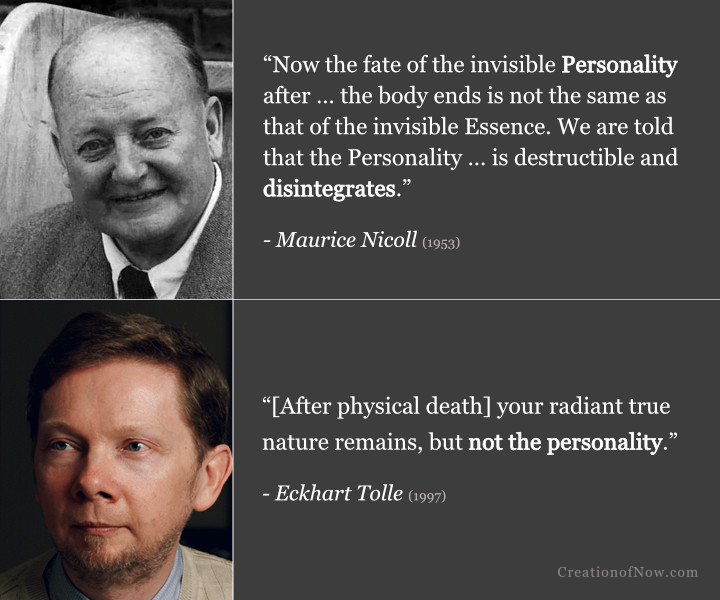

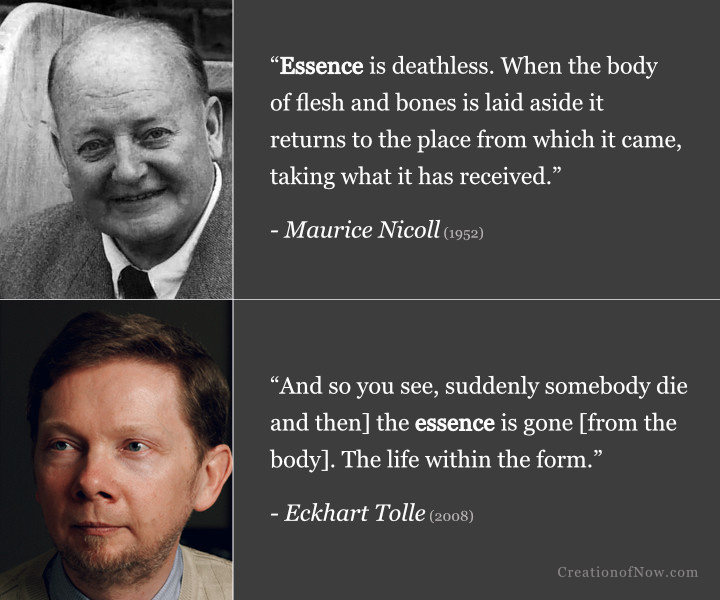

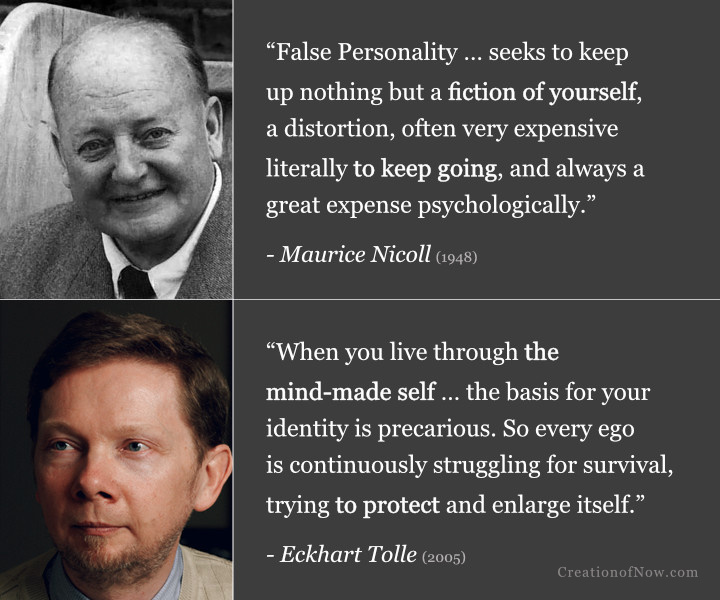

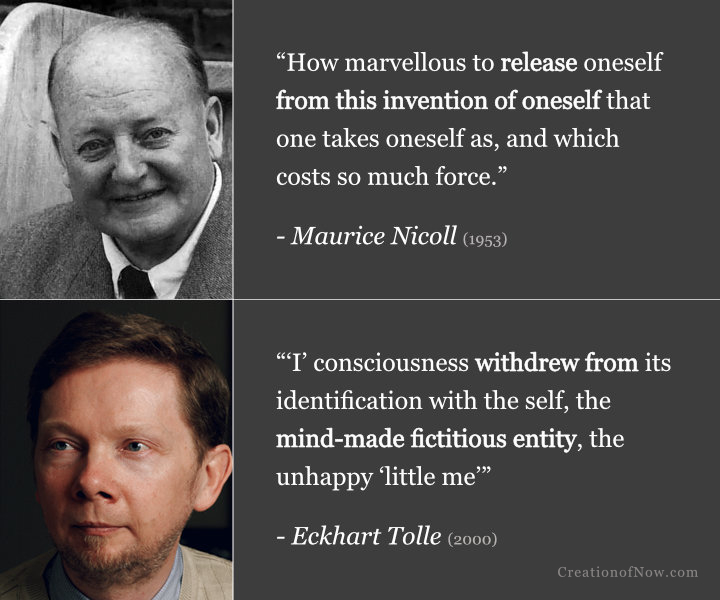

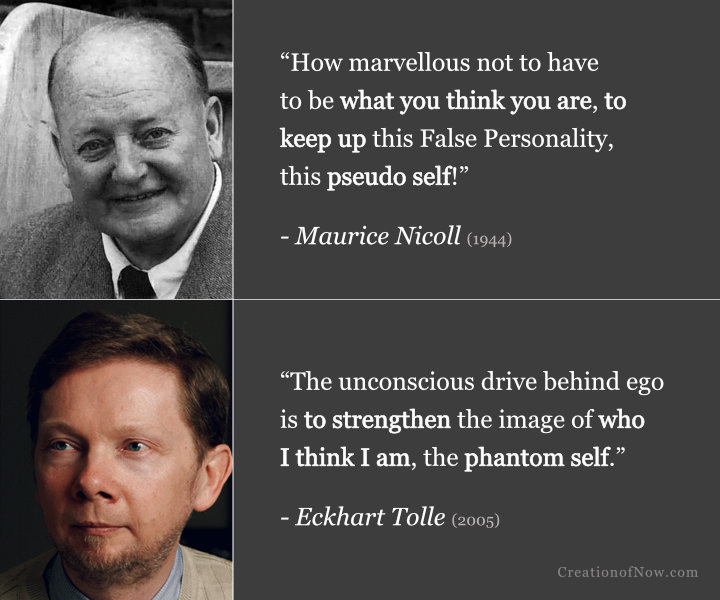

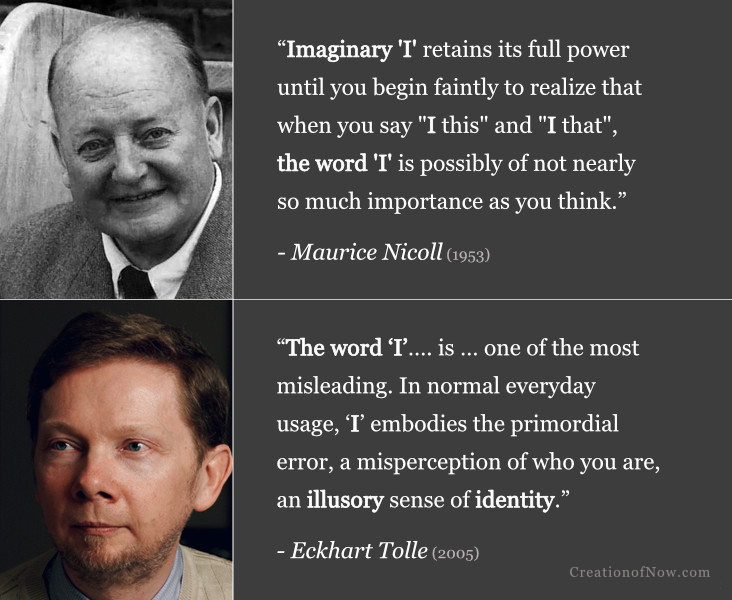

For example, our real, innate, eternal “essence” is said to continue after death, but our transient “personality,” formed by social conditioning, will perish, we are told. Our “false self,” on the other hand, never really existed to begin with: it’s the imagined picture or mental projection of who we think we are (and want others to see us as). Tolle uses the common term “ego” for this aspect, while Nicoll typically employs the Fourth Way term “False Personality.” Despite being unreal, this fictitious, illusory/imaginary idea or image of ourselves is a chief obstacle to awakening, they say, bringing anxiety, fear and conflict. Their focus is on bringing essence, our real and deeper self, to the fore, making personality subordinate to it, and dissolving the false egotistical self entirely.

While their psychological models don’t correspond in all aspects—and differ markedly in some ways I’ll discuss later—they match very closely on these three fundamental attributes of self-identity. The following comparative analysis concentrates on these.

Summary of Correspondences

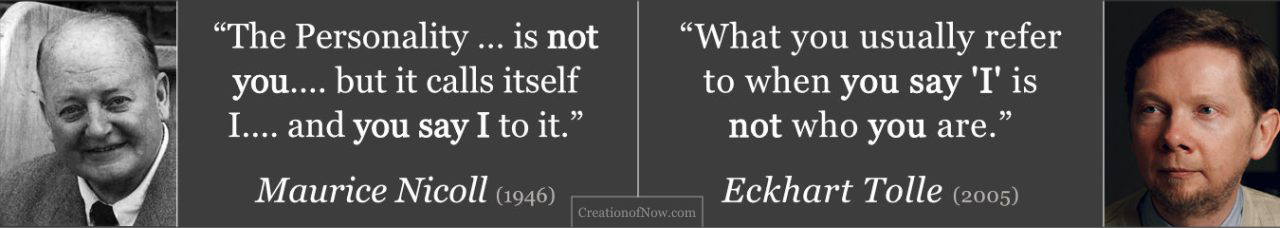

To summarise, Nicoll and Tolle often use the same or equivalent terms to designate three distinct attributes of the psyche that contribute to our sense of identity—to what we may refer when we say “I.” These are:

- Essence – this is presented as our true or real self

- Personality – this is described as a more transient self

- False Personality/Ego – this explicitly labelled a false self

Their correspondence is both conceptual and descriptive; that is, these concepts not only carry the same basic meaning and attributes, but are sometimes described quite similarly too. Here is a high-level summary:

Essence

People are described as possessing “essence” and a “personality” (Tolle sometimes uses “essence identity” for the former and “surface I” or “form identity” for the latter.) Essence is our true, real essential and deeper self, nature or being. Essence is innate, not formed or derived from external influences, and is eternal or timeless. It is “indestructible” and continues after the body’s death. We can feel our essence now through being conscious in the present moment, which takes us beyond identification with passing time, to which the temporal personality is limited. Both authors italicise the word now when making this point. Note that the terms “Real I” and “Deep I” are also used by Nicoll and Tolle respectively, in connection with one’s real self, but with some distinctions (which I’ll come to later).

Personality

The personality, in contrast to essence, is not inborn but developed under external environmental influences, by which habits, “likes and dislikes” are instilled, according to one’s social and cultural environment. Personality is a transient, conditioned aspect, formed in time and limited to it, and is thus a more “artificial” or “superficial” part of us. It carries our name and constitutes our worldly identity, and is a necessary part of human life, but acts as a problematic “prison” if we identify with it too much to the exclusion of essence, as is often the case. The personality is said to perish after the death of the body, unlike essence.

The False Self (False Personality/Ego)

The egotistical “false self,” in contrast to the personality, is completely unreal as well as unnecessary, obstructing self-development and complicating ordinary living too. This “fiction” is an imaginary or illusory idea of who we think we are. Identification with it creates constant unease, friction and disharmony because we want to keep up, defend and protect this invented identity, both to ourselves and others. Nicoll typically calls it the “false personality” while Tolle typically calls it the “ego.” In either case, it’s explicitly designated false and illusory and is said to be egotistical in nature. The authors emphasise becoming free of it entirely.

A side-by-side summary of similarities by concept

Below are tables with side-by-side comparisons of how they correspond on these concepts. This is followed by a deeper discussion of their similarities.

Table 1: the real/true self

| Maurice Nicoll | Eckhart Tolle |

| Termed “Essence” | Called “essence” or “your essence identity” |

| “What we are.” Our “deepest” and “real or essential” aspect; the “real person” | “Who you are.” “Your own deepest self,” “true self” or “true nature” |

| Your “essential being” | “Your very being” |

| Remains “unspoiled” by external life | Nothing that happens can “touch” it |

| “Indestructible” | “Indestructible” |

| “Invisible” | “Invisible” |

| Remains after the body dies—is “deathless” | Remains after the body dies—is “never lost” |

| Is connected with our higher “Real I” or Self | Is also called the “Deep I” |

| People lose touch with “Essence” because they “identify with the personality” | People “unaware of their own essence and identify only with their … psychological form” |

| Unlike personality, Essence is “eternal” and “beyond time” | Unlike personality, essence is “timeless” and of “eternity” |

| Felt or experienced now, when you are fully conscious in the present moment | Accessed in “the Now” when your consciousness is focused on the present moment |

| Entering this state is called “the creation of now” | Accessing this state is termed “the power of Now” |

| “[Real] I dwells in now, and not in passing time.” | “It is only now that you are truly yourself” |

| This “state of consciousness” is “out of time and personality” | “In that state, the ‘you’ that has a past and a future—the personality… is hardly there.” |

| Essence is connected with the “vertical” arm of the cross, representing “the dimension of eternity,” that’s experienced when in this conscious state | Essence is connected with the vertical arm of the cross, symbolising a “timeless” “spiritual dimension” accessed when in this conscious state |

| By inwardly taking this “timeless” and “vertical” direction, one can rise to higher levels/states “of being” | “A deepening of your being” can occur within “the vertical dimension of the timeless now” |

Table 2: the transient self

| Maurice Nicoll | Eckhart Tolle |

| Termed “Personality” | Referred to as “personality,” “form identity” or “psychological form” |

| Is “artificial” | Is “superficial” |

| Formed after birth by environmental/social influences | Formed after birth by “psychological and emotional conditioning” |

| Instilled with “likes and dislikes,” “prejudices” | Instilled with “likes, and dislikes,” “prejudices” |

| “Called by your Christian name and surname” | Carries “a name” and “your historical identity” |

| Exists “on the surface” of what we really are | Also referred to as the “surface I” |

| Becomes what one “takes as oneself, not knowing any better” but is not really you | Becomes “who you perceive yourself to be” but is not who you really are |

| Is “temporal”—“formed in Time, and belongs to Time” | Is “short-lived”—has a finite “past and future” |

| Unlike Essence, personality disintegrates after the body dies | Unlike essence, personality does not remain after the body dies |

| Associated with the horizontal line of the cross, representing the dimension of time | Associated with horizontal line of the cross, signifying the dimension of time |

| “While the Personality is wholly active, the [vertical] direction is closed” | The vertical “dimension of depth” has “nothing to do with the personality” |

| Identification with it makes it a “prison” | Becomes “your prison” through identification |

| Has “covered over” and masked “the real person—the Essence” | “Obscures your true identity;” makes us “unconscious of essence” |

| Must “cease to identify with” it | Must cease to “identify exclusively” with it |

| Must shift your “centre of gravity of consciousness inwards” to make “Essence active” and personality “passive” to it | Must “discover and live from your true essence” instead of letting this ‘surface I’ or “form identity” direct your life |

| The personality is necessary for life, but should not be mistaken for who we really are; it should be passive and subservient to Essence | Plays a role in life and must be honored, but we shouldn’t seek our “ultimate sense of identity” from it; this is found in one’s “essence identity” |

Table 3: the false self

| Maurice Nicoll | Eckhart Tolle |

| Mainly termed “False Personality” or “Imaginary I” and is described as a “False Self” | Mainly called “ego” or the “illusory self”—which is described as a “false self” |

| Also labelled a “pseudo self,” “false I” and a “wrong sense of ourselves” | Also labelled a “phantom self” a “false identity” and a “false sense of self” |

| Described as “a fiction,” “fictitious,” “imaginary,” and “unreal” | Described as “a fiction,” “fictitious,” “illusory,” an “illusion” |

| Is a “fictitious idea that you have of yourself,” a “great fiction” that “we imagine ourselves to be” | It is a “fiction of the mind,” a “fictitious sense of self” or “illusory sense of identity” |

| “As we grow up” this “artificial feeling of ‘I’ … composed of imagination” is formed “by ourselves and by the environmental influences” | This “phantom self” is formed “as you grow up,” from “a mental image of who you are, based on your personal and cultural conditioning” |

| Involves “self-pictures”—“imaginary pictures of ourselves” that we’re “especially identified” with | Involves “an image in your mind,” a “mental construct” we unconsciously identify with |

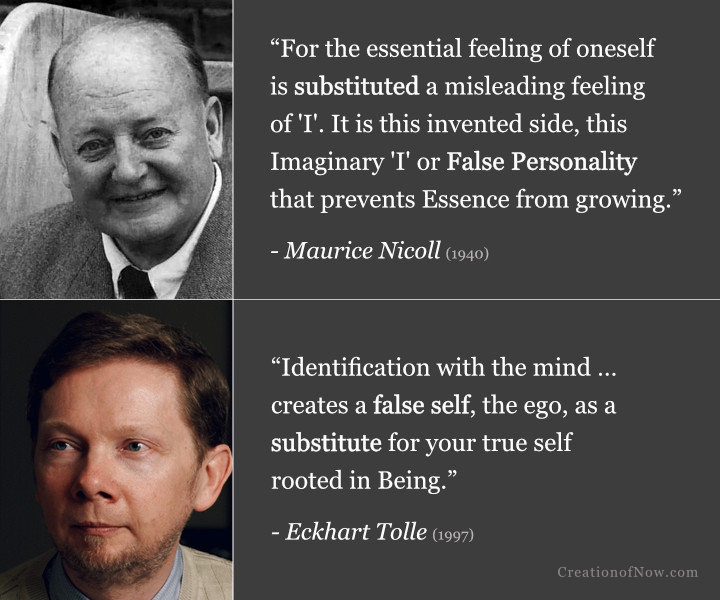

| This “misleading feeling of I” becomes “substituted” for “Essence” | This “false self” becomes “a substitute for your true self” |

| It could be “blatant, loud and boasting” or based on a sense of “Poor little me” | It could be “grandiose and inflated” or based on “seeing oneself as a victim” |

| Is “a negative … egotistical bundle of personal reactions, full of self-fears and hopes, foolish ambitions, daily lying, unnecessary unhappiness, stupid judgments, false pride, imbecile vanity, and all the rest.” | “It consists of thought and emotion, of a bundle of memories you identify with…. long-standing resentments, or concepts of yourself as better than or not as good as others, as a success or failure.” |

| “Confuses and distorts” our “inner world” and is “the source of so much daily misunderstanding and unhappiness and offence” | Produces “misinterpretations of reality” affecting “all thought processes;” results in “selective perception and distorted interpretation” |

| Although “unreal,” this false self nevertheless is “always striving to exist” and “maintain” itself and is “afraid of loss of esteem and position” | “Because of its phantom nature” it “feels vulnerable, insecure, and is always seeking new things to identify with to give it a feeling that it exists.” |

| The strain of “maintaining something unreal” creates much “anxiety and fear” and “nervousness” whether we “admit it or not” | Because it’s illusory, it’s governed by “fear” and “a sense of insecurity” even if “it appears confident” from the outside. |

| Make us “easily offended” and “do all sorts of things in order to keep up this imaginary self, the False Self, this self that is not really deeply us, in order that we … do not lose face—or, in fact, lose all sense of ourselves.” | The ego, therefore, typically “takes everything personally” and drives you to defend “the illusion of yourself” and uphold what is really just “an illusory identity, an image in your mind, a fictitious entity.” |

| “Always justifies itself in order to maintain its existence” and will uphold its “judgments and views and opinions” even if they’re wrong | Defends “mental positions” to preserve itself, using “self-justification, defense, or blaming”—“whether the other person is right or wrong.” |

| The False Personality is “our greatest enemy” which we “serve as slaves” | The mental “voice of the ego” is often “a person’s own worst enemy”—they are “it’s slave” |

| Weakened by consciously observing it, seeing its falsity and ceasing to identify with it | We can go beyond the ego and weaken its grip by observing and disidentifying from it |

| Then we can find “something stronger” within us; fear and anxiety diminish, and relationships improve | Then “a power comes into your life that is far greater than the ego,” fear lessons, genuine relationships become possible |

| When we realise our “own nothingness”—the “unreality” of “False Personality”—we attract and “make room” for “Real I” and thus “become something” | By “becoming ‘less,’ (in the ego’s perception)” you actually “become more” because you “make room for Being to come forward.” |

I will now examine their similarities for each concept in greater detail. This will be followed by a summary, and detailed analysis, of some significant differences they also have in their self-knowledge perspectives.

Essence and Personality Compared

Below is a direct comparison of how the authors discuss essence and personality as distinct psychological components important to our sense of identity. This will be followed up by an examination of a third significant attribute they also describe: the false self.

Essence: the real or true self

According to Nicoll and Tolle, Essence is what is “real” or “true” in us—the innate real, true or essential aspect of who we are—our “true nature” or “essential being.”

Nicoll describes Essence as the “real or essential” part of a person, our “deepest and most real part.” One is said to be born purely as Essence, whereas our personality develops later. “Strictly speaking, Essence is what we are,” and it’s this aspect that is “awake in us” he writes. He describes Essence as our “essential being” and indicates a growth or development in Essence means “a change in the Level of Being”. [5] The term “Real I” is also used to describe a person’s “real self” or “Real Being” with some variation (more on that later).[6]

Tolle also uses the word “essence” or “essence identity” to describe who someone really is – their “true essence”, “true self” or “true nature” or “the essence of who you are.” He describes “your essence identity” as pure “Being” or “your very Being”.[7] Similar to “Real I” being associated with essence in the Fourth Way, Tolle also calls your true essence the “Deep I”.[8]

Personality: a transient self

The personality, in contrast to essence, is not inborn but acquired in life, formed and shaped by the external conditioning or influences of one’s surrounding environment and culture, by which habits, “likes and dislikes” are instilled. Yet we tend to identify with this aspect more than essence, we are told.

The personality is the “artificial figure that life has built up, and that one takes as oneself, not knowing any better,” Nicoll explains. It is developed under external influences after birth, and it soon covers over and masks “the real person—the Essence” as it “takes charge.” It’s this acquired personality that’s “called by your Christian name and surname” and obtains worldly “likes and dislikes, customs, attitudes” according to “the period, the environment in which one is born, school influences, the fashion of the day, the nation to which one belongs and the standards which it sets.” Yet deep down it is “not you” or “the individual himself” and exists “on the surface” of what we really are.[9]

Tolle similarly describes the “personality” as the “superficial” dimension to who you are that’s “conditioned by the past.” Also referred to as your “form identity,” “psychological form” or “surface I,” the human personality, he suggest, is that aspect of ourselves that carries “a name, a past, a life situation, a future” and “your historical identity” in the “world of form.” It constitutes “your psychological and emotional conditioning” including the “likes, and dislikes” you’ve acquired. People unfortunately become identified with their personality and lose touch with their “essence identity.” Because of this, people often mistakenly derive their “sense of self” from their “short-lived form identity” or personality, but this is not fundamentally “who they are” in a deeper sense.[10]

Essence eternal; personality time-limited

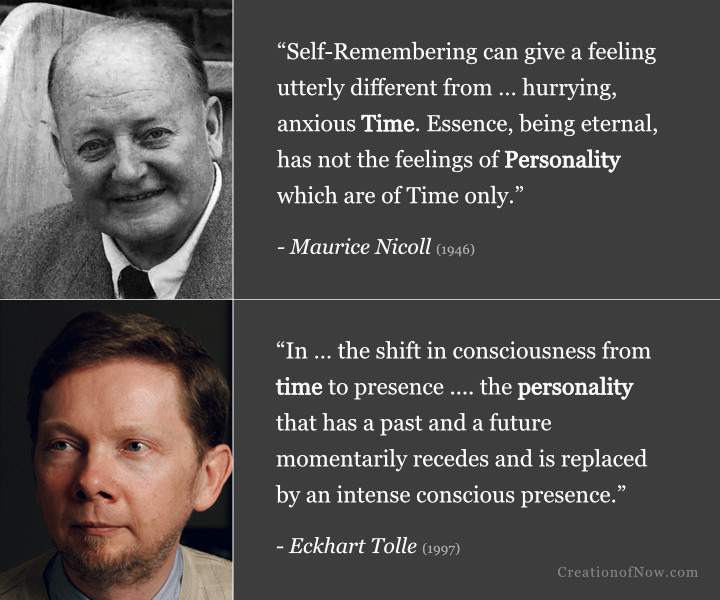

The personality “belongs to Time” or is “time-bound,” we are told. It perishes after the death of the body, whereas the formless or invisible Essence exists beyond time, is “indestructible” and continues after death.

Essence is “indestructible”, eternal, deathless, and exists “beyond time” and “is not of passing Time,” Nicoll tells us, whereas the personality, like the physical body, is “formed in Time and, belongs to time” and thus has an end. “The Essence is the eternal part of us: the Personality is the temporal part of us,” he writes. The personality “is destructible and disintegrates” after the body dies, whereas the “invisible” essence, which is “the real person,” continues to exist after death and “remains after Personality is removed.”[11]

Tolle also conveys that the formless “essence of who you are” is “timeless”, of “eternity” and is “invisible and indestructible”—whearas “the personality” is “time-bound” and “has a past and a future” and therefore an end. When the physical body dies “the essence is gone” from it— “the life within the form.” But since “nothing that is real, is ever lost,” writes Tolle, “your radiant true nature remains” after the death of the body—but “not the personality.”[12]

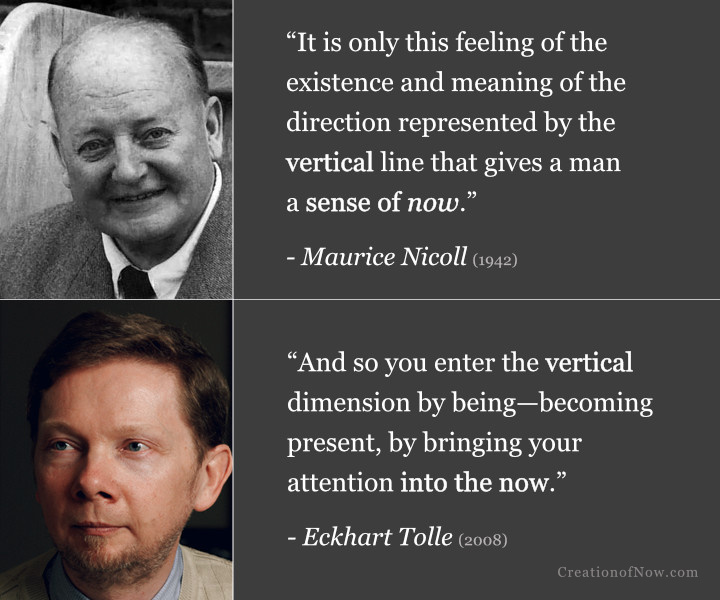

Essence and eternity experienced now

Both suggest that being conscious now is the means to feel, experience or be our real self or essence

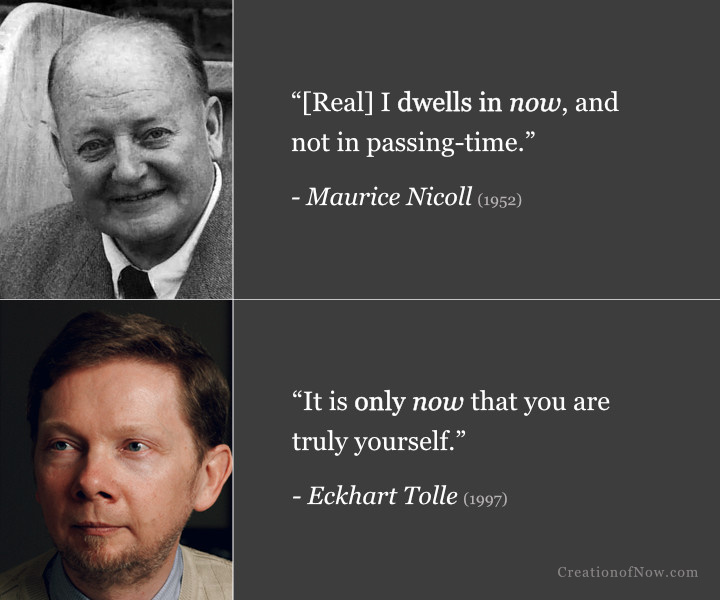

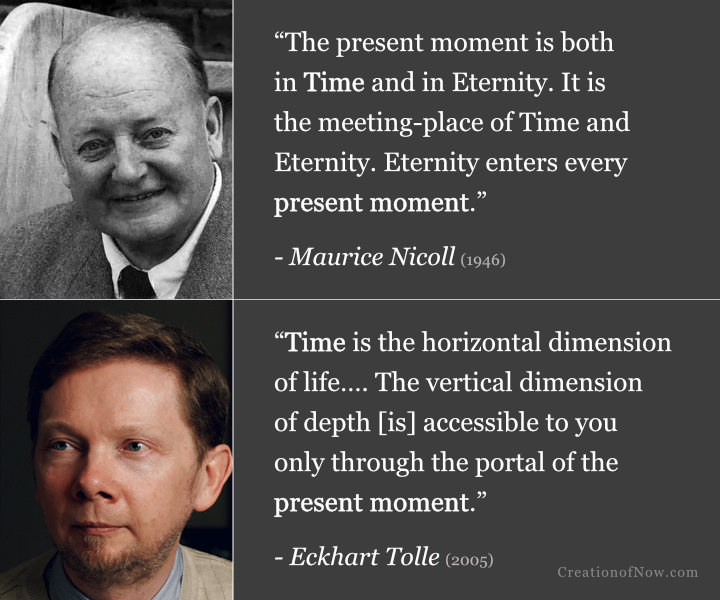

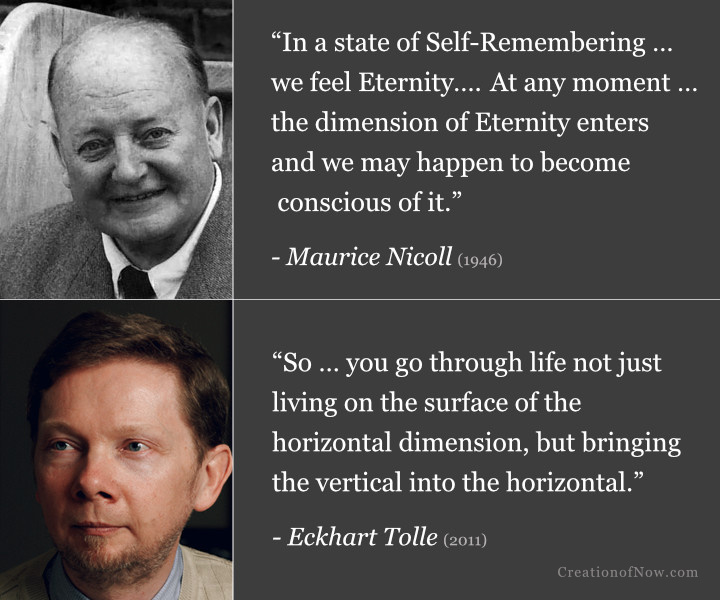

The importance of being conscious in the present moment is a key feature in both author’s work. Nicoll has called this “the creation of now” or the “feeling of now,” while Tolle’s first book, titled The Power of Now, focuses on this theme. Both suggest that being conscious now is the means to feel, experience or be our real self or essence—and both italicise the word “now” to emphasise this. Being in this state is said to take one beyond the horizontal flow of time, to which the personality is limited, into the inner perception of one’s timeless, eternal real self.

“Every now”—that is, every moment experienced consciously—“is eternal” according to Nicoll, and since “all that is genuine, all that is real” exists in eternity, one can only experience their Essence, “Real I” or the conscious “state of oneself” by “the creation of now” which is to “reach a state of consciousness … where one is present to oneself” and “fully conscious, in the present”. The present moment “only becomes now in its full meaning if a man is conscious” within it.[13] This is typically called self-remembering in the Fourth Way:

To remember oneself the feeling of now must enter—I here now—I myself now—I distinct from past or future—the nowness of myself—I now.[14]

This “feeling of oneself now” or “feeling of now” is synonymous with “the feeling of Eternity” because our real self “is in Eternity—not in Time,” explains Nicoll. “The feeling of Eternity enters every moment of Time, but in a direction we can never find as long as we are identified wholly with the Personality” which only “directs us to Time—to passing Time.” “Eternity is always in now and can be experienced as a different taste from Time,” he writes. “Essence, being eternal, has not the feelings of Personality which are of Time only.”[15]

Tolle likewise affirms that your “very essence… is immediately accessible to you as the feeling of your own presence.” This feeling occurs when all one’s “attention is in the Now”. In this “shift in consciousness from time to presence” the time-bound “personality” which “has a past and a future” is “hardly there anymore.” It “momentarily recedes and is replaced by an intense conscious presence.” Yet you are “essentially yourself” and, in actuality, “it is only now” – when one is conscious in the present moment – “that you are truly yourself,” he suggests.[16]

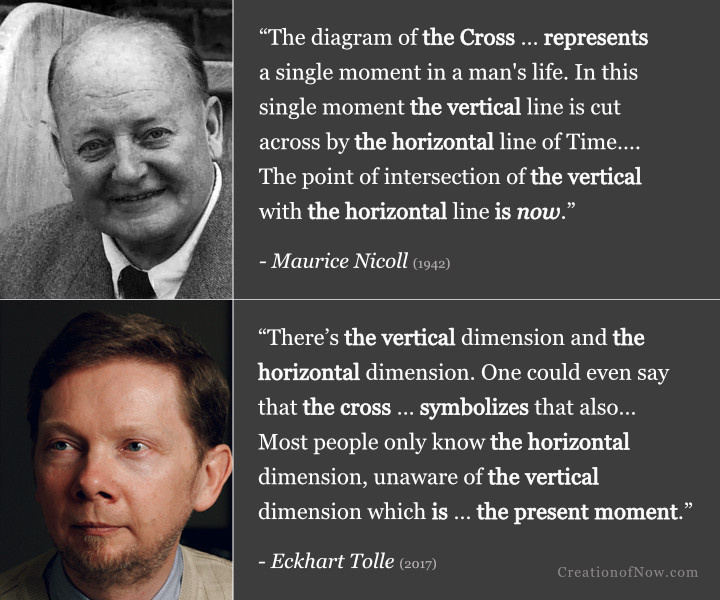

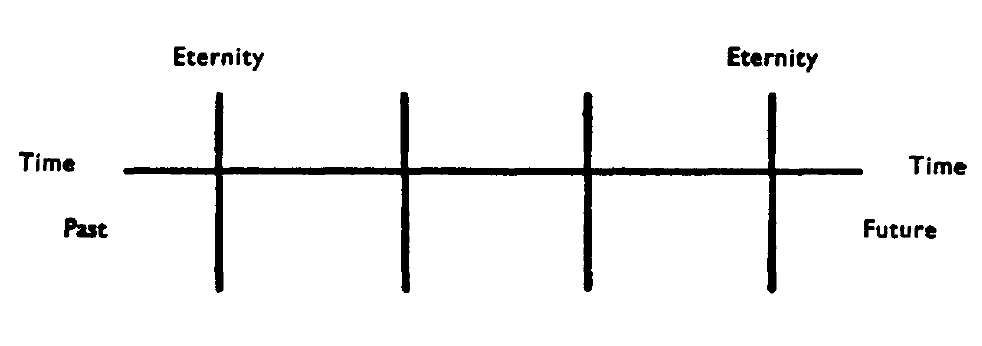

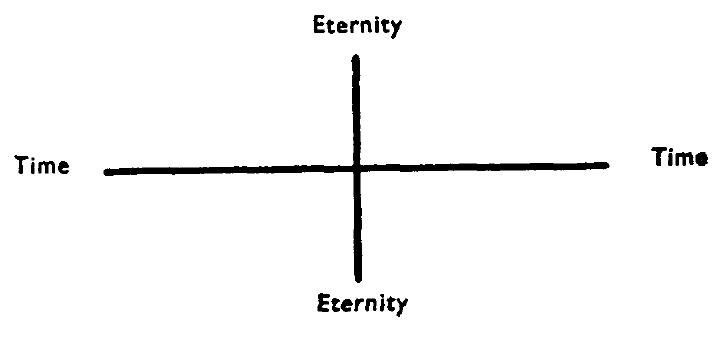

The symbol of the cross

Sometimes the authors describe time and eternity as different “horizontal” and “vertical” dimensions. They suggest one’s real essence or Being is eternal and belongs to the vertical dimension beyond time, accessible through being conscious in the present moment, whereas the personality is limited to horizontal time. Sometimes the symbol of the cross is used to represent the meeting of these two dimensions in the present moment.

“Time and Eternity can be represented as the Cross,” writes Nicoll. This symbol shows how “vertical and horizontal” influences meet “in the point of now” where “the dimension of Eternity” (the vertical line) “enters the dimension of Time” (the horizontal line) in the present moment. “Essence” is “not of passing Time” or “a temporal thing,” and so “belongs to the vertical line” of eternity in which we “have our being”, “essential being”, or “Real I.” Personality, however, is limited to the horizontal line of time.[17]

“Personality is formed in Time, and belongs to Time, whereas essence enters Time and leaves Time. Essence is beyond Time. The quality of essence belongs to the vertical line drawn at right angles to Time—that is to say, essential being belongs here.[18]

The act of Self-Remembering is an “inner movement” in a timeless “vertical direction” that takes one “out of Time and Personality.” As already mentioned, this state is described as “the feeling of now.” “It is only this feeling of the existence and meaning of the direction represented by the vertical line that gives a man a sense of now,” writes Nicoll. “While the Personality is wholly active, the direction is closed,” but “when a man remembers himself he lifts himself in the vertical line upwards and tastes for a moment a new state.” This vertical direction signifies an inexhaustible “scale of states of being” in which one can “rise” to higher levels through “a development of essence”—by becoming “more conscious.”[19]

In the extracts below, you can see a few examples of Nicoll discussing these ideas alongside some of the cross diagrams he incorporated, which are shown in their original locations.[20]

Tolle likewise invokes the cross to express this idea: “There’s the vertical dimension and the horizontal dimension. One could even say that the cross … symbolizes that also.” “A few people have interpreted the Christian cross … as … showing the horizontal dimension of life, and suddenly it intersects with the vertical dimension,” he once remarked (without naming anyone). The horizontal dimension pertains to time, to “past and future,” and is where your “form identity” belongs and your life situation unfolds, he suggests. Whereas the vertical is a timeless and eternal “spiritual dimension” or “dimension of depth” that can only be entered in the present moment by “bringing your attention into the now.” “Who you are in your essence” is to be found in this “vertical dimension of the timeless Now” in which “a deepening of your Being” is possible. This “spiritualization of who you are” within “the dimension of depth, the vertical dimension” has “nothing to do with the personality.” [24] [25] [26] [27]

I could write further about how they correspond on this horizontal and vertical motif, but that would take us beyond the scope of this article. [28] I have discussed enough to show its significance to the concepts of essence and personality we are examining.

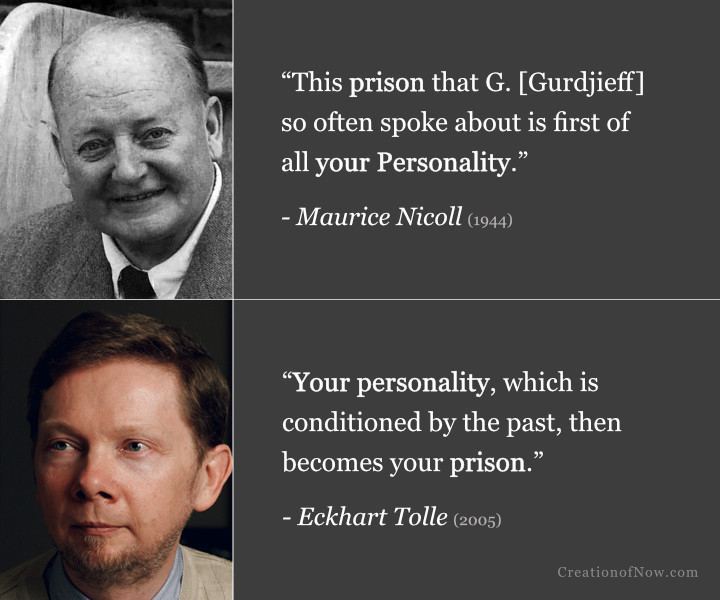

Identification with Personality makes it a “prison”

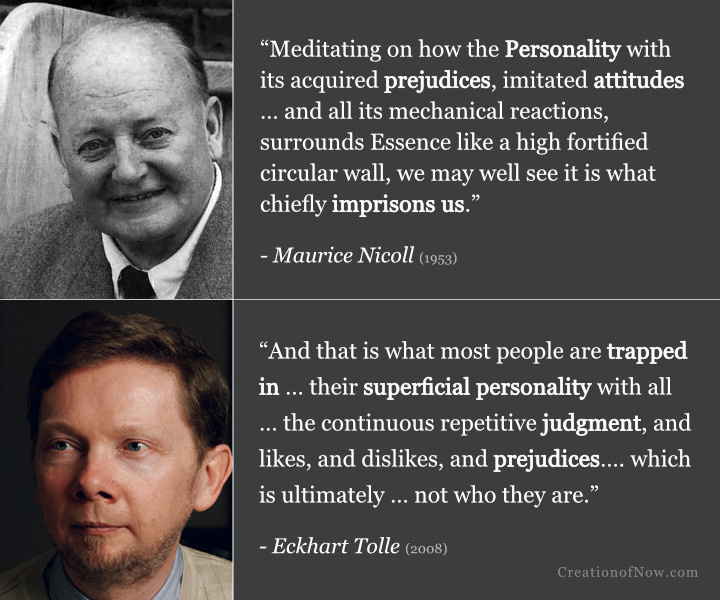

While not who we are deep down, the transient personality has a relative reality and is useful, we are told, allowing us to carry out necessary roles, skills and functions in worldly life. The trouble is that we over-identify with it, taking it to be who we really are, the authors suggest. Then our personality acts like a psychological “prison,” restricting essence. They emphasise shifting our sense of self into essence so it has primacy over personality.

Personality is what a person often “takes as oneself, not knowing any better” writes Nicoll. Though “necessarily acquired,” it is a “prison” when it dominates Essence, which “remains covered over and passive” while personality predominates. This typically happens because external life “makes us identify with the Personality” instead of our timeless essence. We must reverse the situation and make essence “active” and personality “passive” so that it becomes subordinate to essence and no longer “imprisons us.” To do this, “you must observe and separate yourself internally from all that your name stands for in yourself” and “cease to identify with” it. “Observing and separating from the personality allows one to perceive its “unrealness” relative to “Essence” and “draw force into Essence.” This “shifts the centre of gravity of consciousness inwards” into essence, allowing it to develop.[29]

“The struggle is between what is unreal and what is real…. [External] life made and keeps Personality active. The Work is to make Personality passive by the methods of the 4th Way so that Essence can grow and eventually become stronger than Personality, so that a man is no longer worked from outside—from life. This means the emergence of a new man, a new woman. This is the development meant—not an increase of what you are but the emergence of another new person, by making what you are now passive.”[30]

“Relatively speaking, everything belonging to Essence is real and everything belonging to Personality is unreal. I say, on purpose, relatively real and unreal. We understand that Personality must be formed in us before Essence can grow beyond the stage it reaches through its own power of growth. And Essence can then only grow at the expense of Personality—that is, in my case at the expense of Dr. Nicoll or in your case at the expense of this fine man, this superior woman, called—well, called by your Christian name and surname.”[31]

Tolle also suggests that when the “conditioned personality” is “who you perceive yourself to be” it “becomes your prison” that you “get trapped inside.” “Most people are trapped in … their superficial personality,” and “behave and act as if it that were who [they] are.” They “identify exclusively with their own physical and psychological form, unconscious of essence.” This then “obscures your true identity,” the “deeper dimension to who you are” which is “your true essence.” His teachings seek to “help you permanently stay grounded in your connection to your essence identity.” This “frees you from looking only to the ‘surface I’ for your ultimate sense of identity.” [32] [33] [34] [35]

The useful role of Personality

Despite not being our real self, both authors indicate that personality plays a necessary role in life, including for those committed to awakening. This distinguishes it from the false self, which we’ll look at next, which has no useful role at all.

Personality remains useful and necessary, Nicoll tells us, provided it’s made passive and subordinate to essence, which needs to become active.

While personality can restrict essence, it is nevertheless needed for essence to grow, Nicoll maintains. The “development of Essence at the expense of Personality … is impossible unless Personality has been formed first of all,” he writes.[36] This occurs when essence is made active within us and personality passive, as discussed above—which reverses the usual situation in life. For those in the work, Personality remains useful and necessary, Nicoll tells us, provided it’s made passive and subordinate to essence, which needs to become active.

This usefulness of personality stands in contradistinction to the false personality, which is said to have no useful or redeeming role whatsoever and is to be weakened, dissolved or eliminated.[37] “The False Personality” is “distinct from the necessarily acquired Personality itself,” writes Nicoll, and is that part or side of personality that’s purely fictitious and “composed of imagination—of false ideas about oneself.” While the personality proper may be “relatively unreal” compared to the eternal essence, and is not our real self, this “apparatus for experiencing life” does actually exist for a time. The skills and knowledge it acquires are real and useful—not imagined. But the false personality is a self-made illusion that’s “nothing but a fiction”—an “imaginary self” or “False Self.” Psychologically, it is “what is least you.” [38]

“False Personality is the unreal thing in us. Personality is not really in the same category. All of us have to have strong Personality in ourselves. For example, we all have to learn our jobs in life and be able to do something more or less in life. Personality is the acquired side and the Work says you should have a good acquired Personality before you can really do this Work, but False Personality is quite different.”[39]

“Personality has been built up by life and there is a particular part of Personality, as you know, called False Personality, which has taken the place of any real essential feeling of ourselves. So trying to see one’s False Personality is one of the most important starting-points of self-observation, because unless one can separate from this fiction of oneself nothing can shift internally.”[40]

“If everyone lived more or less within the orbit of Essence and real Personality as distinct from False Personality, they would probably find their lives quite different from the lives of those who follow False Personality.”[41]

The significance of this distinction between personality and false personality is sometimes overlooked. This is likely because the two concepts are closely related and can be described in overlapping ways. Since, as we shall see, the false self is said to be a sort of façade overlaying the “real personality,” the two are connected; the former is described as being the unreal aspect of the latter. The boundaries between them are therefore blurred and not exactly clearly delineated. Perhaps they cannot be drawn so definitively, at least not easily or exactly, precisely because they overlap.[42] Nevertheless, the distinction between them is an important one and distinguishes the Fourth Way from certain other teachings that call for the abrogation of any sense of personal or individual worldly identity.

A good summary of this distinction can be found in Basic Self-Knowledge by Harry Benjamin. This was written as an introduction to the esoteric psychology of the Gurdjieff system based essentially, its author tells us, “on Dr. Nicoll’s Psychological Commentaries.”

“We have made it clear that the individual we know as ourselves is merely the personality—the outer husk as it were—and not the real self, which remains unknown throughout life unless one learns about its existence through esoteric study and training. The personality itself can be divided into two parts: false personality and, personality proper. According to the Gurdjieff system false personality is by far the larger portion of what we regard as our personality, being made up of all those elements which go to swell our ego, such as pride, vanity, self-conceit, imaginations and day-dreams about ourselves, etc.; whereas personality proper is that part of personality which has been developed during life through education, vocation, training and study of all kinds, etc. In short, personality proper is the part of personality which is of real value in earning our living, and making us acquainted with the “know how” of existence. It contains within it all aptitudes, abilities, and prowesses which we may have acquired or developed through life. It is therefore something of real value although not part of the real self of man. False personality, on the other hand, that part of personality within which we mostly live, is of no real value to us. During esoteric training false personality is essentially that part which must be weakened if we are to make any true headway towards becoming real people. In other words, false personality is our greatest enemy; it is the enemy lurking forever within us ready to destroy and devour us.”[43]

Thus one is not told to discard the personality proper for spiritual growth, just because it is transient, any more than one would discard their physical body; it’s our inner relationship to it that must change. But false personality, we are told, is completely unnecessary and should be discarded entirely (we’ll come to this in the next section). Weakening and destroying the False Personality so it no longer dominates the “real personality” allows Essence to become active, grow and direct the personality instead.[44]

One of the teachings of this Work is to make Personality passive. In order to do that you have to see and observe what keeps Personality active in such a way that you always feel you are right. As long as False Personality dominates Real Personality the latter will be under the wrong leader and go in the wrong direction.[45]

An effective personality is not only needed for practical life, Nicoll tells us, but to receive esoteric knowledge. One must, for example, know a language to receive an esoteric teaching. For the same reason, the transmission of a teaching requires a sufficiently developed human culture—and that entails facilitating the development of personality in people.[46]

“Now Essence, since it comes from the stars, is at a higher level than Personality which is formed in us by life on the manifest Earth. Essence, being therefore a higher thing, is a much more real thing. Yet it is undeveloped—a child that has to be taught, at the expense of Personality. You will say: “How can the lower teach the higher—the higher by origin in scale?” I will answer you and say that the Personality—the lower—cannot teach Essence, the higher, unless the Work enters Personality. Then the Work, coming from outside, from what you hear and learn, will speak to Essence from Personality…. The Work must come from outside, from schools in the world, and so enter first the Personality. This is why one task of Esoteric Humanity was to raise culture to a degree in which people could hear and understand enough to take in the Work. The Personality had to be built up, by education, by all the arts, sciences, literature and so on, to make it possible for mankind to grow and keep open a connection between “Sun” and “Earth”— or, if you use the language of the Gospels—between Heaven and Earth.”[47]

A comparable distinction between personality and the false self is found in Tolle’s work too. However, as in the Fourth Way, there is substantial overlap between these concepts here too. This is even more apparent with Tolle because, to the best of my knowledge, he makes no attempt to clearly differentiate these concepts like Nicoll does.

According to Tolle, one’s “personality,” “surface I” or “form-identity” is not to be rejected; its role in human life should be honoured.

Nevertheless, these two distinct categories can be recognized in Tolle’s work by how he talks of each concept in very different ways—and in a manner corresponding to the Fourth Way definitions we’ve just outlined.

According to Tolle, one’s “personality,” “surface I” or “form-identity” is not to be rejected; its role in human life should be honoured. He speaks of integrating the real self—that is, our Deep I, essence identity or Being—with our human personality. This is reminiscent of the Fourth Way idea of making personality passive and subordinate to essence. In contrast, however, the egoic false self is never discussed neutrally or as something to be retained in a process of integration, but as something to be discarded altogether—and that is the key difference.

Tolle’s teaching is supposed to “help you remain in touch with your essence identity” in life. This changes your attitude to the surface I, but does not abolish it. Rather, it “frees you from looking only to the ‘surface I’ for your ultimate sense of identity”—which can only truly be found in your essence identity or Deep I. The object then is to “discover and live from your true essence” while living out the roles of your “surface I” without “knowing yourself” exclusively as the latter anymore.[48] [49]

“This realization of yourself as the ‘Deep I’ is so freeing, so liberating, because you’re being liberated from the burden of knowing yourself only as the ‘surface I’ and its so-called ‘drama.’ When you realize yourself as the ‘Deep I,’ it enables you to have a compassionate attitude toward everything that makes up the ‘surface I’—your physical form, your personal identity.”[50]

These two aspects, a temporal worldly identity and the deeper essence identity, are also expressed, Tolle suggests, but the conjoined term “human being”—with “human” denoting the temporal aspect and “being” the deeper self: “Human is form. Being is formless.” The human aspect “has its place and needs to be honoured,” he tells us, but cannot give true fulfilment alone—only your formless Being can do that. There must be “a balance between human and being.”[51]

Tolle relates that it took “many years, about ten years” to “integrate” his new state of consciousness with his still-existent “personality.”

“Being … is the deeper, true I,” Tolle explains. “When I know myself as that, whatever happens in my life is no longer of absolute but only of relative importance. I honor it, but it loses its absolute seriousness.” We must honour “this physical dimension that our surface selves inhabit” yet be “aware of the eternal underneath the forms.” “So I’m not saying not to honor the level of form,” he comments. “Whatever you do in this life, this horizontal level where we do things, where we have our functions and play roles, you honor that level but [we should be] realizing there is something more vital; there is something deeper than just that.”[52] [53]

Notably, Tolle also indicates that, after awakening, “the new state of consciousness” still needs to be “integrated” into an individual’s life so that it “flows into and transforms everything they do.”[54] After his own purported awakening experience, Tolle relates that it took “many years, about ten years” to “integrate” his new state of consciousness with his still-existent “personality.”[55] [56]

However, the integration, because there is a personality here, there is the Awakening and then for a while the personality continues almost as before, it has the same goals as before. [So] there was [initially] no understanding, what so ever, about what [my] Awakening meant. I didn’t even call it Awakening. I didn’t have a name on it. So it took years to understand what had happened and it took years for it to fully take hold of my life. So [that] it was no longer engaged in activities that were not compatible with awakening for example. [Emphasis added][57]

Yet while “the personality continues” after awakening, the same cannot be said for the egoic false self. According to Tolle’s often-repeated account, his “false suffering self” “collapsed completely” and “immediately” during his awakening experience. The collapse of this “fictitious entity” was so complete and immediate, that it was “just as if a plug had been pulled out of an inflatable toy.”[58] [59] It could not, therefore, still exist from that point on, according to him. So we can be sure he’s not referring to this false egoic self when he speaks of the integration with the personality after awakening.

Both authors clearly suggest that the personality is retained and has its place in spiritual awakening, yet assert quite the opposite with the false self

And herein lies the key distinction in Tolle’s work between the personality and the ego or false self. The former has its temporal role and is apparently retained during and after awaking; the higher consciousness must integrate with and “flow” into it, redirecting its goals and activities—but the ego is a hindrance that is, ideally, entirely eradicated during awakening. This differentiation somewhat mirrors the distinction between personality proper and false personality described by Nicoll. As in the Fourth Way, these two aspects of our worldly identity overlap in Tolle’s rendering also—and perhaps more so, as he doesn’t lay out a definite system with clearly defined terms like Nicoll does. Nevertheless, the distinction between these two aspects can be clearly discerned by the different fates he accords to each—one collapses or dissolves, while the other continues and must become integrated with awakened consciousness.

Thus, in summary, both authors clearly suggest that the personality is retained and has its place in spiritual awakening, yet assert quite the opposite with the false self. I’ll now look more closely at what they say about the latter.

The false self: nothing but trouble

The “False personality” described by Nicoll is analogous to the ego in Tolle’s writings: both are explicitly designated a “false self.” While the ordinary personality, discussed previously, has its place in both everyday affairs and spiritual awakening, our false self can be our worst enemy and has no useful place at all. Awakening entails becoming free of it, we are told.

The authors use some comparable descriptive terms for this false aspect of our identity. Nicoll mainly uses the Fourth Way terms “False Personality” and “Imaginary I” to designate this “egotistical” aspect; he also calls it a “False Self,” “False I,” a “great fiction,” an “imaginary self,” a “fictitious ‘I’” and generally describes it as “fictitious”. Tolle uses the labels “false self”, “illusory self”, “phantom self”, “fictitious entity” and, most of all, “ego” to refer to this “fiction of the mind.”

The false self/personality acts as a psychological substitute for our true or essential self, the authors say.

Both define it as our false conception of ourselves, typically shaped by our upbringing, environment or culture and the resulting image or pictures we form of ourselves—of who we imagine or think we are. This self-portrait may be based on attributes of the functional personality, but is typically distorted. This false self is substitute for what we really are, and is sustained and strengthened by near-constant identification with it, and one usually goes on believing they are this false self until, or unless, they observe and stop identifying with it, we are told. It produces largely negative psychological effects, they suggest, and is the source of much unhappiness and dysfunction in human beings. Both write of dissolving it entirely.

I’ll now compare how they present this concept more closely.

A fictitious invention

Nicoll defines False Personality as “the person we imagine ourselves to be” which is “nothing but a fiction of yourself” or a “fictitious idea that you have of yourself” that’s “composed of self-evident lies and false imagination.” It is the “invented person” or “pretended person” we imagine ourselves to be, formed of false and imaginary “ideas about oneself” and “self-pictures,” that is, “imaginary pictures of ourselves.”

Every one of us, whether we are good at life or not, has very strong False Personality. Let us begin by saying that False Personality is an invention of yourself—a pretence. It is something unreal in you.[60]

Out of the imagined pictures and ideas we form of ourselves, “a false feeling of oneself is created, a false feeling of ‘I’.” We become “especially identified” with “this dressed-up invented thing,” this “fiction of ourselves,” which means we typically derive our “sense of ourselves,” our identity, from this “False Self” or “pseudo-self.” But this false idea of ourselves or “False ‘I’” is typically “a distortion” skewed by fantasy, delusions, self-importance, self-centredness, vanity, wrong self-estimation, overvaluation, anxiety and negative emotion etc.[61] It is not necessarily boastful though; it may, for example, be centred in self-pity:

Some people think of False Personality as being something blatant, loud and boasting. But this is wrong. False Personality in one person may sing: “What a fine fellow I am”, and in another person sing: “Poor little me”.[62]

Unlike the personality proper, false personality is completely unreal, being “constructed out of imagination.” Yet it acts as the “controlling power” or “guiding devil” of the personality. This means that, psychologically, we are effectively “run by” this “fiction,” “invention” or “pretence” which is something “unreal” and “not ourselves at all.” [63] [64]

Tolle likewise defines the “false Self”, or “ego” as “an illusory sense of identity” or “illusion of yourself” which is “ultimately a fiction of the mind” with a “phantom nature.” This “fictitious sense of self,” “illusory self,” “phantom self” or ego consists, he suggests, of “thought and emotion”, “an image in your mind,” “a bundle of memories you identify with” and “personal identifications.”[65]

The term ego means different things to different people, but when I use it here it means a false self, created by unconscious identification with the mind.[66]

Thus to Tolle, the ego is merely a “phantom self” that is a “mental image” of who we “think” we are—a “mental construct”—and so nothing more than an “illusory identity” or “fictitious entity.” He also suggests that this “egoic self” or “false identity” can be quite varied in different people; its conception depends on what you “identify with” as “me and my story”—which then “gives definition to” a person’s “self-image.” While some people, for example, may form a “grandiose and inflated” self-image, other egos can be based on “seeing oneself as a victim.”[67]

Who [some people] think they are is this: “I am a needy ‘little me’ whose needs are not being met.” This basic misperception of who they are creates dysfunction in all their relationships…. Their entire reality is based on an illusory sense of who they are.”[68]

The “unconscious identification with the mind” creates and sustains this “false, mind-made self.” People strongly identify with their ego, Tolle suggests, but it isn’t real, nor is it who they really are.[69]

Formed during upbringing

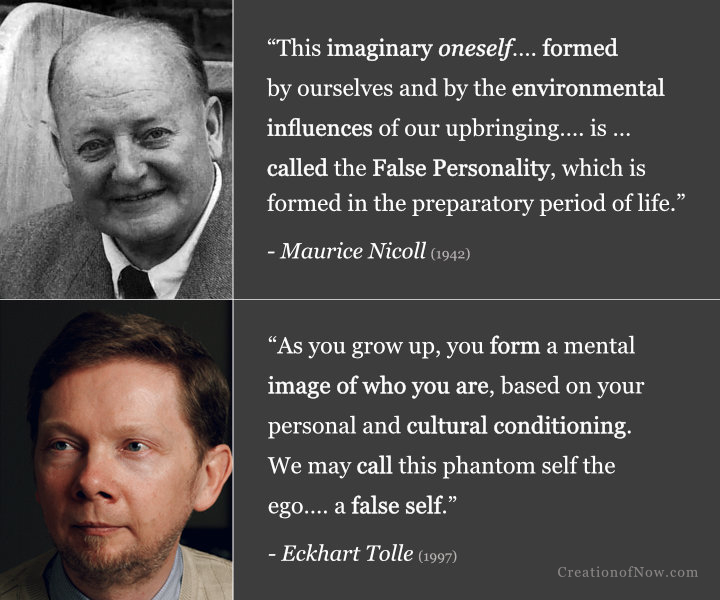

Both authors make clear this false sense of who we are is formed as we grew up and shaped by one’s surrounding culture or environment.

Nicoll relates that the “False Personality or Imaginary ‘I’” is shaped “as we grow up” and is “formed by ourselves and by the environmental influences of our upbringing”, and appears first “in the preparatory period of life.”[70]

Tolle likewise states the ego, which is “false self” or “phantom self,” is formed early on “as you grow up,” from “a mental image of who you are” which is “based on your personal and cultural conditioning.”[71]

The false self/personality is formed by the environmental/cultural influences/conditioning of our upbringing and the imaginary idea or image we form of ourselves, the authors convey.

Distorts reality, creates conflict, fear

The false personality “confuses and distorts” our “inner world” and relationships, Nicoll conveys, producing largely negative effects. He describes it as a “negative and small-minded, egotistical bundle of personal reactions, full of self-fears and hopes, foolish ambitions, daily lying, unnecessary unhappiness, stupid judgments, false pride, imbecile vanity, and all the rest.” False personality is “the source of so much daily misunderstanding and unhappiness and offence” because whenever our self-estimation is “touched” we can be “easily offended.” It makes us “afraid of loss of esteem and position” and “do all sorts of things in order to keep up this imaginary self, the False Self, this self that is not really deeply us, in order that we … do not lose face—or, in fact, lose all sense of ourselves.” Although “unreal,” this false self nevertheless is “always striving to exist” and people struggle to keep up and defend their “imaginary idea of themselves” because their sense of identity is so centred in it. This leads to strong tendency toward self-justification, even when we are wrong, in order to uphold the “judgments and views and opinions” of our False Personality which “always justifies itself in order to maintain its existence.”[72]

“We are easily offended and upset because False Personality is our feeling of ourselves and it is an imaginary thing, an acquired artificial mask, a pretended person that we like to imagine ourselves to be and are not…. The keeping up of the False Personality takes a great deal of force…. it exhausts us.”[73]

“Anxiety and fear, which prevent us relaxing, subtly arise when a man endeavours to maintain what is not really himself…. So we cannot deeply relax … for False Personality will keep on making us correspond to what it imagines itself to be. It will not allow a person to be at rest, but must prod him to act in the way he is supposed to act, to keep up his reputation, his character-role…. It makes each of you keep up your pictures of yourself.”[74]

“Remember, the more you find yourself self-justifying the more certain you may be that you are lying to yourself. The False Personality, however, is very powerful, and will maintain itself at all costs and by every method, one of which is self-justifying.”[75]

The effort to keep up and maintain the False Personality, which is merely “something imaginary,” results in “anxiety and fear.” The fact that reality often challenges “the imagination that you are living in” “keeps us in anxiety” and the strain of “maintaining something unreal…. weakens us so much and renders us so brittle, so easily upset.” Frictions, misunderstandings, negative emotions, and unconsciousness inevitably arise. The False personality is thus a fiction that’s “very expensive literally to keep going, and always [at] a great expense psychologically.” For these and other reasons, Nicoll calls it “our greatest enemy” which we “serve as slaves.” But if we could “see by direct insight that that we are not at all as we imagined,” via self-observation, he maintains, “then the power of False Personality would be weakened.” We would no longer feel compelled to act merely “to satisfy our fear, to keep up our False Personality” and instead find “something stronger” within us. Then our inner life, and relationships with others, would change for the better, and “all this anxiety and nervousness which all secretly feel about themselves, whether they admit it or not, would vanish.”[76]

Tolle also conveys that this false egoic self produces “misinterpretations of reality” which results in “selective perception and distorted interpretation” affecting “all thought processes, interactions, and relationships” in an often negative way. The ego “consists of certain repetitive and persistent thoughts, emotions, and reactive patterns that you identify with most strongly” which are “invested with a sense of self.” But it is a very precarious and insecure sense of self, he tells us. “Because of its phantom nature” the ego always feels “vulnerable and insecure” and “under threat” ”—“and so lives in a state of fear and want” where it’s “on guard against any kind of perceived diminishment.” Since it’s formed through “mind-based” identification, then “if you identify with a mental position … your mind-based sense of self is seriously threatened with annihilation” if you’re shown to be wrong. “So you as the ego cannot afford to be wrong. To be wrong is to die….” The ego is thus characteristically defensive, and will use such means as “self-justification, defense, or blaming” to preserve itself, “whether the other person is right or wrong.” [77]

“When you live through the mind-made self comprised of thought and emotion that is the ego, the basis for your identity is precarious because thought and emotion are by their very nature ephemeral, fleeting. So every ego is continuously struggling for survival, trying to protect and enlarge itself.”[78]

“The ego is always on guard against any kind of perceived diminishment. Automatic ego-repair mechanisms come into effect to restore the mental form of “me.” When someone blames or criticizes me, that to the ego is a diminishment of self, and it will immediately attempt to repair its diminished sense of self through self-justification, defense, or blaming.”[79]

“Ego takes everything personally. Emotion arises, defensiveness, perhaps even aggression…. You are defending yourself, or rather the illusion of yourself, the mind-made substitute. It would be even more accurate to say that the illusion is defending itself.”[80]

Because this “phantom self” lacks any real security, Tolle suggests, “the underlying emotion that governs all the activity of the ego is fear.” “This false, mind-made self feels vulnerable, insecure, and is always seeking new things to identify with to give it a feeling that it exists.” It thus carries an inherent “fear of loss” and “anyone who is identified with their mind and, therefore, disconnected from their true power, their deeper self rooted in Being, will have fear as their constant companion.” Moreover, “there is always a sense of insecurity around the ego even if on the outside it appears confident,” he explains. The ego, therefore, typically “takes everything personally” and drives you to defend “the illusion of yourself” and uphold what is really just “an illusory identity, an image in your mind, a fictitious entity.” Tolle suggests the mental voice of the ego is often “a person’s own worst enemy” and characterises our incessant identification with it as “enslavement.” Only by observing the ego in yourself can you begin to go beyond it, he indicates. If the ego’s grip were lessened this way, he suggests, then “a power comes into your life that is far greater than the ego.” Then more genuine relationships with others would become possible, and we would cease to feel so much fear and anxiety.[81]

Observing and dissolving the false self

The practice of self-observation has a central place in the work of both Nicoll and Tolle, and they describe the importance of using it to see and break free from the false self.

Nicoll writes of the need to observe “your False Personality, what you imagine you are, and absolutely cancelling this fictitious idea that you have of yourself.” “To change, you must lose your ordinary feelings of identity,” he writes, and “move away from this spurious person you have taken yourself as and served as a slave.” The False Personality is “weakened by [the] genuine inner perception of its unrealness” via self-observation, and being in a conscious state deprives it of its power. This “will gradually dissolve the Imaginary ‘I’, the False ‘I’, the False Personality, that one has hitherto taken as oneself.” The “light of consciousness which illuminates things in us” is the agent of change, Nicoll suggests, and “seeks eventually to bring about the collapse of everything fictitious and unreal.”[82]

“All self-realization, all self-knowledge which is real, destroys the imagination of oneself—i.e. the False Personality.”[83]

“When the light of self-observation is thrown into this dark side, consciousness of ourselves increases through self-knowledge, and after a time we begin to feel differently from what we used to feel. The centre of gravity of ‘I’ in us begins to change. In other words, Imaginary ‘I’, this ‘I’ that we are always serving and keep going, which is not ourselves at all, begins to be dissolved. We find that we are nothing like what we imagined and as this takes place so do our relations to other people expand. Instead of living in a narrow world of prejudices, of violent likes and dislikes, owing to the expansion of consciousness in ourselves we find a larger relationship with other people. This is due to a growth of consciousness by the method of uncritical observation which is the basis of the whole Work on its practical side. The result is that this sensitive bundle of personal reactions, this continually being upset and hurt, this inability to meet any criticism from others, begins to disappear, and we enter a larger world.”[84]

Tolle has described how his false self “collapsed completely” when he observed it and realised this “mind-made fictitious entity” wasn’t real. His consciousness “withdrew” from its identification with this “unhappy and deeply fearful self, which is ultimately a fiction of the mind.” Every time the ego is observed and “recognized” within you, Tolle maintains, it “is weakened.” Any unconscious patterns of your “illusory identity” will “dissolve in the light of your consciousness” when you consciously witness them. “The recognition of illusion is also its ending,” he explains; by consciously seeing and recognising its illusory nature “the ego will lose its grip on you.”[85] [86]

I’ve examined how Nicoll and Tolle discuss the importance of observing the false self before. Here is a summary of the main points I’ve already covered—with links to the locations I’ve discussed them in more detail:

- Nicoll and Tolle stress the importance of observing and ceasing to identify with the false self. Observing it impartially takes the feeling or sense of “I” or “self” out of it and places it in conscious observation instead; this weakens its grip upon us.

- Both write of the need to observe negative emotions arising in connection with the false self—for example when we are offended or feel our self-estimation or self-image threatened. These negative emotions are expressed via an unnecessary psychic apparatus with no other purpose: Nicoll writes of the “negative part of the emotional centre” being the culprit, while for Tolle it is the “pain-body.”

- The light of consciousness is directed upon the false self by this process, which reveals its falsity. It is weakened and may be dissolved in this light—and eventually collapse entirely, we are told. Nicoll insists this is a gradual process, while Tolle suggests it may happen swiftly for some.

- Only by consciously seeing and recognising what you are not, can you come to recognise what you really are. The recognition of the fictitious nature of our false self is pivotal to knowing one’s real self.

This last point was only briefly discussed previously, and I’ll add something to it now. As well as recognising unreality of the false self, we must be willing to let this false idea of ourselves diminish—and so feel ourselves become “nothing” or “less” in comparison to what we thought we were, the authors suggest. This diminishment in our self-estimation, or self-image, is necessary to “make room” for what is real—for Real ‘I’ or Being.

Allowing one’s false sense of self to diminish—and thus become less or nothing in relation to what we thought we were—draws real “I” or Being to us, the authors suggest.

“It is impossible for any of us to add a cubit to our stature by ourselves,[87] but the False Personality thinks it can and it will fight to maintain itself,” writes Nicoll. But if instead of trying to maintain it, you “begin to feel your own nothingness,” then you likewise “begin to receive the help of the Work to replace that nothingness by something.” Then we can act from “what is most simple and humble and genuine and sincere,” in us, and begin to attract help from higher influences. By suffering the loss of what is unreal, we “make room for something else to enter us” and attract “Real ‘I’.” Thus if someone: “realizes clearly that he is nothing. Then he can become something.”[88]

“So the Work teaches that when a man or woman comes to the point of realizing his or her own nothingness, then this [recognition of] nothingness attracts Real ‘I’. For if you are over-swelling with yourself and your virtues and value, how on earth can you come in contact with anything real? So Self-Remembering … can never be based on your self-merit, but only on a gradual … profoundly emotional … inner perception of the truth about yourself—of your own unreality which hitherto you have taken as yourself.”[89]

“And then at last we begin to see what it means that a man must realize that he is nothing before he can expect to be something.”[90]

Similar to Nicoll’s assertion that we must realise our “own nothingness” to attract and “make room” for “Real I” and thus “become something”—Tolle suggests that by “becoming ‘less,’ you become more” because you “make room for Being to come forward.”[91]

“Through becoming ‘less,’ you become more. When you no longer defend or attempt to strengthen the form of yourself, you step out of identification with form, with mental self-image. Through becoming less (in the ego’s perception), you in fact undergo an expansion and make room for Being to come forward.”[92]

In closing this segment about the False Self I will reiterate a key point: in contrast to the transient personality which is said to be retained in the process of spiritual awakening—if in a reduced and subordinate role to one’s real self or essence—the false self must be diminished or dissolved for the awakening process to occur, the authors make clear. This is the key distinction made between these two aspects of our worldly identity: the personality, as we’ve seen, is merely temporary, but has uses in life when appropriately utilised, they suggest. Yet the false self is entirely unreal as well as useless. This false self must be greatly diminished—ideally removed—during this life, they insist, if one’s awakening is to progress.

Some points of difference

While the authors correspond in describing the three core aspects shaping our self-identity I’ve outlined—a real self, transient self and a false self—they do not correlate in how they view the psyche in every respect. Here are a few important points of difference. I’ve summarised these in a table; a longer discussion follows.

Table 4: Author differences

| Maurice Nicoll | Eckhart Tolle |

| False personality is not “easily seen and destroyed…. and its strength is extraordinary.” | “To become free of the ego is not really a big job but quite a small one.” |

| Awakening and dissolving the false self, or bringing about its collapse, is a gradual process | A swift awakening where the ego collapses “immediately”—as in his own account—happens in “rare cases” with “rare beings.” But it’s a gradual process for most. |

| It takes inner work, effort, sacrifice, struggle and time to awaken. | Omits emphasis on work, struggle, sacrifice or any time requirement. Hopes “the word work” will disappear. |

| “Conscious suffering” occurs by eradicating “self-love” and its effects, and replaces ordinary unconscious suffering as the latter is sacrificed within. It only comes to exist through conscious inner work. | “Conscious suffering” involves letting go of inner resistance (non-acceptance) of “what is,” including any unconscious psychological pain within. All psychological suffering is primarily unconscious. |

| It is impossible to awaken, and dissolve the false self, without overcoming pride, vanity and all such offspring of “self-love.” Mentions these factors hundreds of times and discusses the need to overcome them at length. | Overcoming pride not emphasised. Across his two major books pride is only mentioned in passing three times, vanity once (in a quote) and self-love never. Not fundamental to becoming free of ego in his worldview. |

| “Real I” is a person’s higher “real self” that their “Essence,” having descended into the world, must reconnect with. | The “Deep I” and “essence” are discussed interchangeably, with no apparent distinction. |

| Teaches the “doctrine of ‘I’s,” which holds that “many, many selves” or “I’s” exist in us, as distinct living “entities” or “sub-personalities,” beneath the facade of our overarching false self, and must be observed. | Does not teach the doctrine of many I’s. However, he once mentions that an addiction can function as “a quasi-entity or subpersonality” and should be observed. The “pain-body” is also described as a living entity. |

The difficulty of dissolving the false self

While the authors agree on the need to dissolve the false self, they disagree markedly on the timeframe and difficulty involved in this; Nicoll insists it is a difficult and gradual process, while Tolle suggests it happens swiftly for some

Nicoll, for example, says this on the difficulty of destroying the False Personality:

This absurd thing composed of self-evident lies and false imagination you might think easily seen and destroyed. On the contrary its existence is most difficult to see and its strength is extraordinary. It will neither allow itself to be found out nor allow ourselves to find ourselves out—that is, what we really are. If it did, its power would be destroyed, and we should be free from our greatest enemy—that is, the person we imagine ourselves to be, whom we serve as slaves from the moment we wake up in the morning to the moment we fall asleep at night.[93]

Tolle, on the other hand, writes that “to become free of the ego is not really a big job but a very small one. All you need to do is be aware of your thoughts and emotions – as they happen.”[94] “As soon as you honor the present moment, all unhappiness and struggle dissolve, and life begins to flow with joy and ease,” he also writes.[95] As I’ve pointed out before, Tolle tends to downplay any difficulties involved in awakening and in confronting unconsciousness generally, writing, for example, that inner peace is “not something that you need to work hard for or struggle to attain.”[96] On this, he is very out of step with Gurdjieff’s emphasis on “conscious struggle” [97] or “conscious labour” and “intentional/voluntary suffering” which is so central to the Fourth Way.[98]

But despite Tolle’s insistence that a complete awakening can happen near instantaneously in “rare cases” with “rare beings”—and, as we’ve seen, he describes such an event happening to him—he also mentions, in a few scarce instances, that for “most people” awakening is “a process they undergo” and “have to work at.”[99] And this is a curious admission, not only because he avoids giving a clear outline of the work process “most people” have to go through, but because he also expresses hope that “the word work” will “disappear from our vocabulary.”[100]

The Real or Deep I

Nicoll and Tolle also use the terms “Real I” and “Deep I” respectively (typically capitalised) to designate one’s real self, along with essence. While Nicoll describes “our essence” as “our deepest and most real part,” he differentiates “Real I” or “Real Being” as a higher part of our real self that Essence, having descended into the world, must reconnect with. Essence, he says, “comes from the stars”—which signify, psychologically, a higher level that’s internal and invisible. He sees the work of awakening as an inner “return journey” or ascent by Essence back to its higher origin, where Real I awaits. We can only reach or get in touch with Real I through Essence. On this theme he quotes something Gurdjieff said: “Behind Essence lies Real I, and behind Real I lies God.” [120] Tolle, in contrast, speaks of Essence and the “Deep I” or ‘Being” interchangeably with no apparent distinction.

The doctrine of many I’s

There is a major component in Fourth Way psychology which is not found in Tolle’s work. The “doctrine of many I’s” holds that “many, many selves” exist within our personality. These I’s or egos are viewed as the ultimate cause of most unconscious behaviour and psychic manifestations, whether emotions, thoughts, feelings or actions.[121] Given this is a defining Fourth Way idea that’s heavily discussed by Nicoll, it would be remiss of me not to raise this.

Closing comments

I have argued that Tolle corresponds with Nicoll’s Fourth Way framework in positing three major, over-arching aspects of self-identity: a true self, a transient personality, and a false self. While there are various iterations of teachings speaking of the ego as a false self, and extolling the importance of realising our true self (self-realisation), the idea of a transient self—personality—being a distinct component from either of these, yet still a necessary factor in the self-realisation process, is a notable and pronounced feature of Fourth Way psychological teachings. It is interesting that we find analogous concepts in Tolle’s work, presented with similar terms and descriptions.

I should point out, however, that you won’t find these three categories clearly outlined and differentiated in Tolle’s books. Nicoll was expositing a system as he understood it,[132] and thus spent much time explaining the fine details and meanings of terms and ideas, but Tolle does not teach a system as such. His message is far vaguer on the specifics. I’m not aware of Tolle ever clearly clarifying, for example, the difference between the personality and the illusory ego like Nicoll does with the personality and false personality.[133]

Both authors posit that we have real self, a transient self and a false self…. Both tell us to weaken and discard the false self, make personality secondary, and give our true essence the prime, central place in our lives

But these three distinct categories can still be discerned in Tolle’s work. The real self, “essence identity,” “Deep I” or “true nature” is evident enough. Likewise the false self—the ego—and how to become free of it, is an ever-present focus. However the transient personality—sometimes called the “surface I” or “form identity”—is not so clearly differentiated or defined by Tolle. Nevertheless, I’ve shown that this concept is present in his worldview, is analogous to the personality in the Fourth Way—and is often enough called by this same name too. It can be distinguished from the other two concepts by the indicative ways he describes it.

To reiterate, unlike your “innermost invisible and indestructible essence” which is timeless and deathless, the personality perishes after the death of the body, according to Tolle.[134] But also unlike the egoic false self—which is an illusion to be dissolved or completely collapsed—the personality remains present in this life even after a supposed complete awakening. As we’ve seen, one has to integrate the higher state of consciousness that awakening brings with their personality—so that this more temporal, surface self can understand and act in accordance with the deeper aims of the true self, according to Tolle.

This corresponds to the Fourth Way idea of making Essence the active driver of our inner life and ensuring that personality, and its outer aims, are made passive and subordinate to its spiritual needs. “The invisible Essence” Nicoll makes clear, is eternal and “indestructible”; it is the real part of us that can grow and develop spiritually. Personality, in contrast, is time-limited and disintegrates after death.[135] But it’s still necessary for life, he makes clear, including for those committed to an inner work.

On the need to entirely rid oneself of the third aspect—which both explicitly describe as a false self—the authors also clearly agree (though not, it seems, on the time-frame or effort required).The defining characteristic of the false personality and ego is that it’s never spoken of in neutral terms like the personality can be. Both present it as a central psychological affliction we must weaken, dissolve or transcend.

Thus we can see that Nicoll and Tolle correspond closely not only in the practical side of their work concerning self-knowledge, which involves self-awareness and self-observation, but in their conceptual model of the psyche. Thus the opening question, “what do we mean when we say ‘I’?” has three major (if not exclusive) answers according to the views they outline. Both authors posit that we have real self, a transient self and a false self which usually predominates. Both tell us to weaken and discard the false self, make personality secondary, and give our true essence the prime, central place in our lives so that, more and more, this is what we mean when we say “I.”

It is worth repeating, however, that although Tolle corresponds closely with Nicoll in both his theoretical and practical approaches to self-knowledge—conceptually as well as descriptively—I’m not aware of him ever mentioning having read or studied Nicoll or the Fourth Way. There is certainly no mention of this in his bestselling books, from which most of his material discussed in this, and previous articles, has been drawn.

Nevertheless, this is not the only notable way Nicoll and Tolle correspond on matters of esoteric psychology, as I’ve already shown. I will examine further commonalities in the future.

Raymond Lamb

Thank you., a very helpful summary of the differences in these topics. I enjoyed revisiting these aspects of Nicoll ‘s Commentaries and also the references to Eckhart Tolle’s work which I read a few years back, but are much less clear in my mind.

Jack Dawes

Thanks, glad you enjoyed it.