Self-observation is integral to inner-transformation, Maurice Nicoll and Eckhart Tolle affirm. We must impartially observe the unconscious stream of thoughts, emotions and reactions occurring in us, they say, and cease identifying with our inner states. This is a close look at the many similar ways they explain this practice.

G.I. Gurdjieff, a mystic from Armenia, brought an esoteric system to the West in the early 20th century with self-observation as its primary self-knowledge practice. Today, it’s central to the message of widely-popular author Eckhart Tolle too. While Tolle’s approach, emphasis and terminology can vary in his bestsellers—and is paired with more optimistic New Age perspectives—many fundamentals of the practice are there. Dr Maurice Nicoll, a Jungian psychiatrist, gave copious attention to self-observation in his five-volume work, Psychological Commentaries on the Teachings of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky, published in the early 50s. His explanations have been highly influential, extending, I argue, to the work of Tolle, today’s most famed contemporary author on spirituality by some rankings.[1]

But while Tolle’s bestselling books, talks, videos and media appearances reach a broad mainstream audience, Maurice Nicoll and other “Fourth Way” teachers do not. And because Tolle is not exactly clear about the origins or prior history of self-observation as he conveys it, it’s doubtful those unfamiliar with Fourth Way teachings would have recognised the influence of this tradition and the important place one of its signature practices holds in Tolle’s work. So the story of the rise of this once obscure practice to prominence may have passed unnoticed for many. Here, I highlight corresponding ways Maurice Nicoll and Eckhart Tolle present fundamental aspects of self-observation, which suggest Tolle has interpreted and syncretised at least some aspects of this Fourth Way practice into his popular self-help/spiritual message.

This is part one of a series of articles examining Nicoll’s influence on Tolle’s presentation of self-observation, a practice both authors uphold as integral to inner transformation. In this first part, I compare the similar ways they describe how to undertake the practice of self-observation and use it to overcome identification with inner states.

Summary of correspondences

In comparing the work of Maurice Nicoll and Eckhart Tolle, I have found they present self-observation in a number parallel ways, such as emphasising similar ideas, giving comparable tips and advice, using the same or similar terms, phrases or examples to illustrate equivalent points. In other words, there are similarities in both style and substance. Most obviously, they both use the term “self-observation” to describe an equivalent practice. Nicoll, however, uses this term much more often as it is “standardised” in the Fourth Way; in Tolle’s case it is used infrequently, being one of a number he uses for the same practice or process.

Before going further, you may want to read my introduction to this series of articles on self-observation if you haven’t done so yet and are unfamiliar with the authors or concepts, as it provides some background. Certain points in the following outline might appear obscure without some prior familiarity or context. Otherwise, continue reading for a top-level summary of the key correspondences explored in this article. Following this, we’ll dive into a more in-depth comparison of the authors’ work on each point and, in the process, explore what they mean and convey in more detail.

To summarise, these are corresponding points Nicoll and Tolle make when describing how to practice self-observation. They both:

- Write that “self-observation” involves directing your attention inwards to observe your inner states impartially in daily life.

- Describe the need to observe thoughts, emotions, reactions, desires, moods, behaviour, feelings etc. as they occur in the moment.

- Refer to the “power of self-observation” specifically and suggest this improves with practice

- Explain that observation should bring consciousness or awareness of what’s occurring within us—without any inner judgment, analysis or criticism.

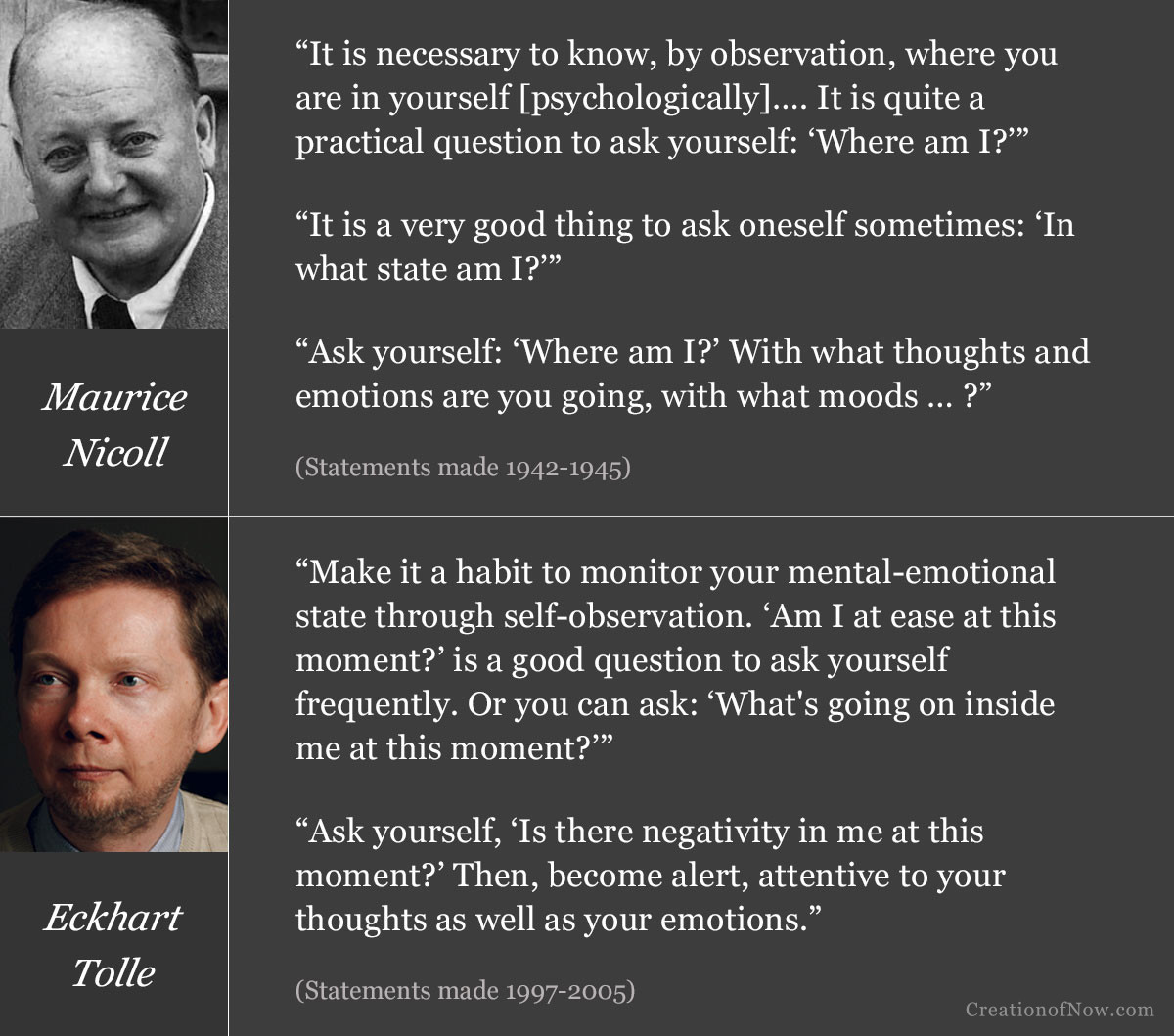

- Suggest it is a good idea to pose questions to yourself that prompt self-observation like: “In what state am I?” (Nicoll) or “What’s going on inside me at this moment?” (Tolle)

- Clarify that observing what is happening within should not be confused with thinking about it.

- Make a number of corresponding points about the importance of observing compulsive or habitual thinking, at times using closely matching phrases/examples:

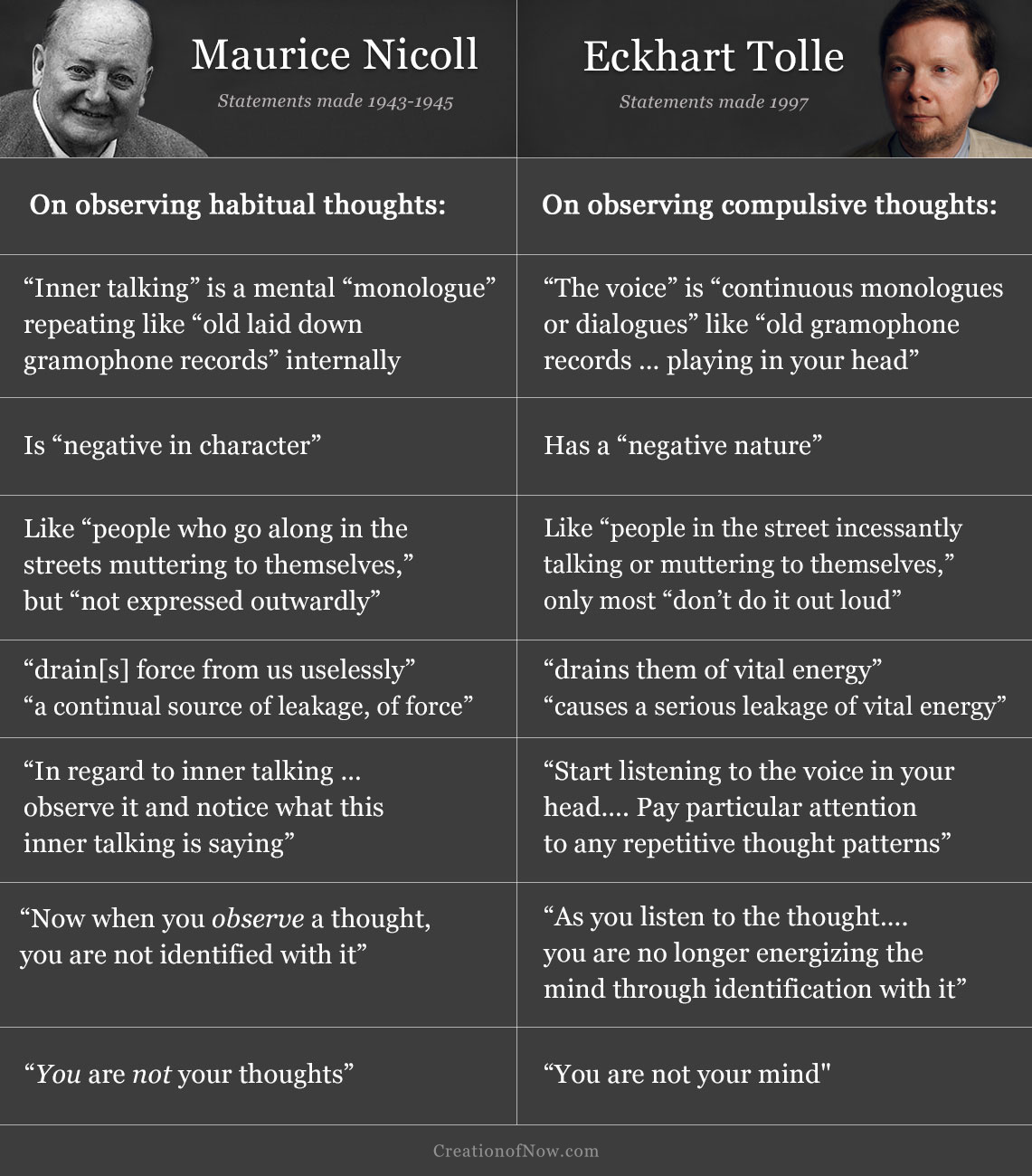

- There are repetitive thought monologues that often replay in our heads like “gramophone records”: Nicoll calls this “inner talking” and Tolle calls it “the voice.”

- These are usually negative and likened to those of people “muttering to themselves” in the streets, just not expressed aloud.

- They are said to drain us, causing a constant “leakage” of force or energy.

- We need to observe and become aware of our thoughts and stop identifying with them.

- Our thoughts are not us: “You are not your thoughts” (Nicoll); “You are not your mind” or “thoughts processes” (Tolle)

They also correspond in numerous ways around the central idea of using self-observation to overcome identification with inner states:

- Both uphold self-observation as the primary means to overcome “identification” with inner states, thoughts, negative emotions and our false psychological self.

- To carry this out is called “non-identification” (Nicoll) or “disidentification” (Tolle). This is presented as integral to inner transformation by both authors.

- The observing consciousness that breaks identification with inner states has similar designations: Nicoll calls it “Observing I” and Tolle calls it the “observing presence” among other names.

- They use variations of the term “identification” numerous times throughout their work in similar ways.

Since overcoming identification through self-observation is a large and complex topic, I’ll break down their correspondences in more detail further on, once we come to it.

First off, I’ll compare the similar ways the authors describe how to actually practice “self-observation,” often employing the same or similar terms, phrases, points and examples in the process.

Practising Self-Observation

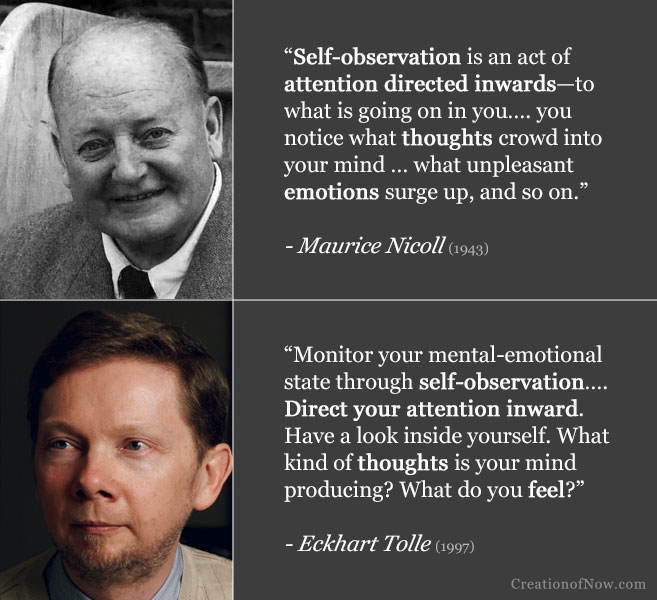

Self-observation is presented as a practice to use and apply in daily life, and Nicoll and Tolle give similar descriptions, advice and tips on how to approach it. To start with the most fundamental points, Nicoll and Tolle both explain that self-observation involves deliberately directing one’s attention inwardly to see what is happening within oneself, psychologically, at a given moment.

Directing attention inwards

Nicoll calls self-observation an “act of attention directed inwards” and elsewhere states that “self-observation is inner attention”. This “directed attention” is used to observe one’s thoughts, emotions and inner states in a detached way.[2] When explaining “self-observation” Tolle similarly writes that you “direct your attention inward” to see your thoughts, feelings and inner state. This observation is done impartially. In another place he writes, “Just watch. Focus your attention within”.[3]

Observing inner states in the moment

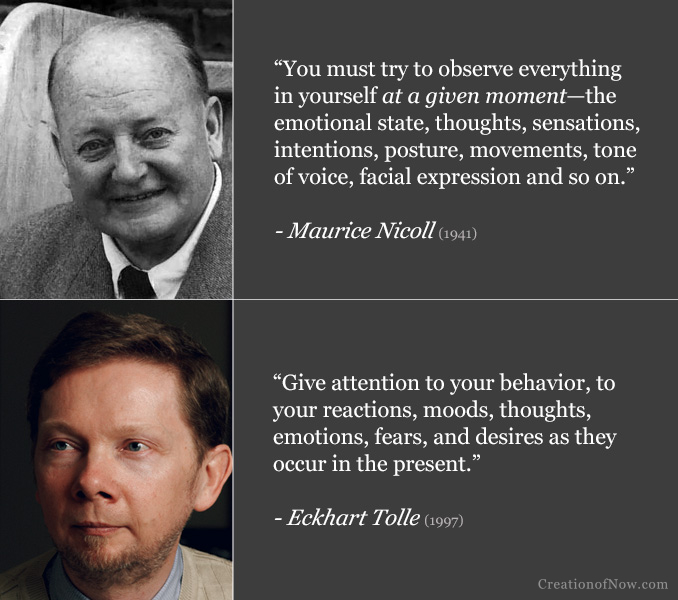

The two authors point to a similar range of psychological functions to observe or “catch” with this attention, as and when they occur. Nicoll refers to observing your own thoughts, emotions, moods, feelings, behaviour, desires, reactions to life’s events, what you feel, and inner states. “You must try to observe everything in yourself at a given moment,” he explains.[4] Tolle similarly refers to observing thoughts, emotions, desires, reactions to situations, behaviour, moods, feelings and your inner state. One should watch all those things “as they occur in the present,” he tells us.[5]

Developing the “power of self-observation”

The “power of self-observation” is a specific phrase both authors use. They portray self-observation as a power that can be developed and improved with practice.

Nicoll describes self-observation as an inner sense, faculty or power, and uses the phrase “power of self-observation” multiple times. “The power of self-observation is an inner sense, rarely used,” and most people employ “no power of self-observation” he tells us. But this power “can be developed” and increased if we “train ourselves” to use it. “By practice you can observe your mood more and more distinctly,” he writes.[6]

In a similar fashion, Tolle maintains that people should become accustomed to using self-observation to monitor their thoughts, emotions and inner state. “You need to have some power of self-observation, which is another word for awareness,” he tells us. “With practice, your power of self-observation, of monitoring your inner state, will become sharpened.” [7]

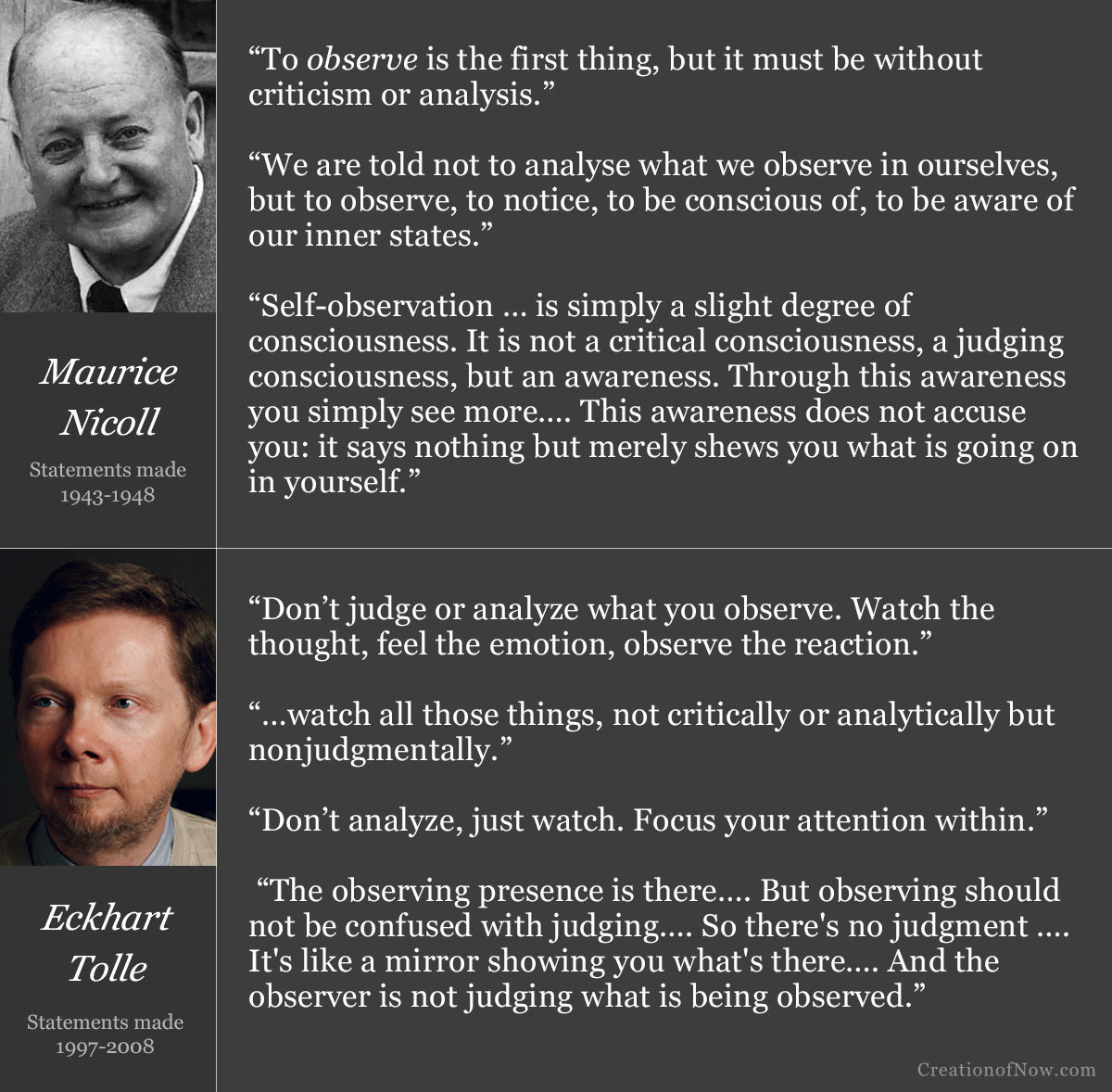

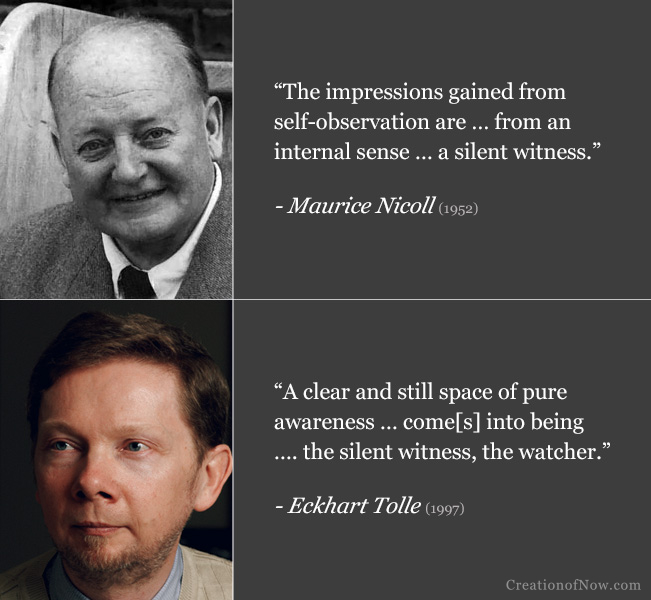

Observing without analysis, criticism or judgement

We are advised to observe our psychological content uncritically, without analysing or judging, but to simply watch with awareness. On at least one occasion, each describes this observing faculty as a “silent witness.”[8]

Nicoll, for instance, tells us to observe “without criticism or analysis”. One is “not to analyse” their inner states while doing so. Self-observation should be an “uncritical” awareness—and “through this awareness you simply see more.” This “consciousness” or “awareness” is not “critical” or “judging” what is seen; it “says nothing” and “does not accuse you” but simply “shews you what is going on in yourself.”[9]

Tolle likewise tells us not to “judge or analyze” what is observed. He tells us to watch reactions, moods and thoughts “not critically or analytically but nonjudgmentally”. “The observer is not judging what is being observed,” he states. The “observing presence” or “the observer” is “consciousness” or “pure awareness.” This “conscious presence” is “the silent watcher of your thoughts and behaviour”.[10]

Posing questions to prompt self-observation

In contrast to most, though not all, approaches to modern mindfulness practice, self-observation is primarily done in one’s everyday activities, in the midst of life, and, as already touched upon, encompasses one’s behaviour, actions, impulses and reactions, as well as the inner factors prompting them.[11] These habitual processes usually go unnoticed, but Nicoll and Tolle give a similar tip to focus one’s attention within: asking yourself questions that prompt you to observe yourself.

Nicoll suggests “In what state am I?” is “a very good thing to ask oneself” to prompt self-observation. He also proposes we ask “where” we currently are in our “inner space” and then observe the thoughts, emotions and moods one has at that moment. “Where am I?” is suggested more than once for this and “where am I living in myself at this moment?” is also “a very good question to ask yourself” he tells us (both meant psychologically). Nicoll describes how the resulting “act of attention, due to self-observation” brought by the question “may change your position in yourself, and get you into a better place” internally.[12]

For his part Tolle also suggests that questions can be used to help you “make it a habit to monitor your mental-emotional state through self-observation.” “Am I at ease at this moment?” is “a good question to ask yourself” he tells us. “What’s going on inside me at this moment?” is another that “will point you in the right direction.” “Is there negativity in me at this moment?” is also suggested, after which one should “become alert, attentive to your thoughts as well as your emotions.”[13]

Observing is not thinking

It’s often pointed out in this kind of literature that people tend to confuse actual self-observation or awareness with thinking about the concept of it.[14] As we have seen, the authors describe observation as silent attention or awareness without analysis. This observing attention must be “continuous”[15] or “sustained”.[16] But they also explicitly address this misconception, pointing out that observing is not thinking—and italicise “thinking” when making this point.

Nicoll writes that people “mistake thinking for observing.” But “to think is quite different from observing oneself” and “observation” is “not the same as thinking” he writes. Self-observation “requires directed attention,” whereas thoughts and emotions belong to all that must be observed with this attention.[17]

Describing the observation of an emotion, Tolle writes that putting your attention on it “does not mean that you start thinking about it”—you “just observe” it. In another place he advises to “focus attention” on the feeling inside you but “don’t think about” or “let the feeling turn into thinking” but just “be the observer” of it.[18]

Habitual or compulsive thoughts: observing “inner talking” or “the voice”

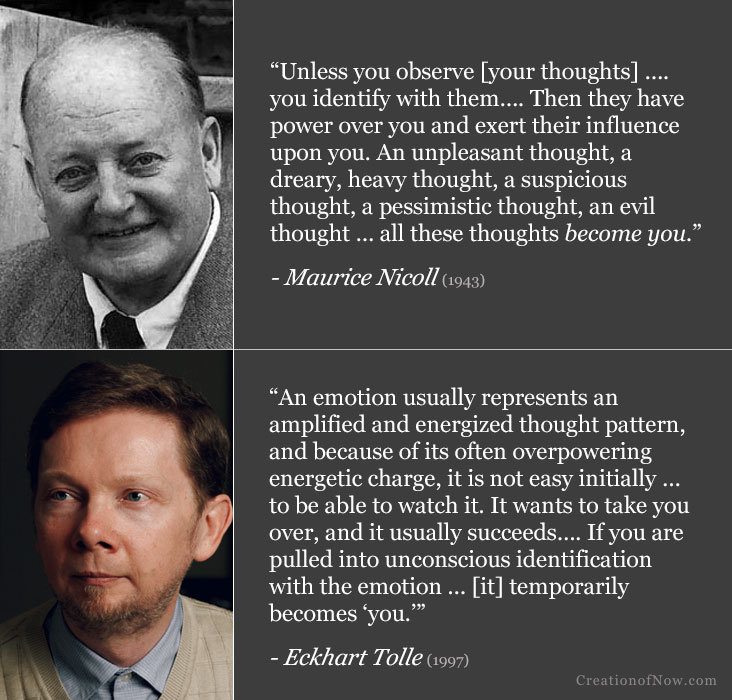

Nicol and Tolle both explain that most thoughts are automatic or compulsive—and are often negative and repetitive like “gramophone records”—and insist we need to stop identifying with our habitual thinking. [19] [20]

The mental monologue

I’ve mentioned before that Nicoll refers to the negative mental “monologue” in us—the “old laid down gramophone records”—as forms of “inner talking.”[21] He compares this phenomenon to “people who go along in the streets muttering to themselves,” only it occurs inwardly, in our thoughts, “all the time” and is “not expressed outwardly.” [22] Tolle refers to these “continuous monologues or dialogues” or “old gramophone records … playing in your head” as “the voice”—and compares it to “people in the street incessantly talking or muttering to themselves,” only most “don’t do it out loud.”[23]

A leakage of energy

In both cases, this mental voice or inner talking is strongly identified with. It is basically “negative in character” and “is a continual source of leakage, of force” that will “drain force from us uselessly” according to Nicoll.[24] Tolle likewise refers to its “often negative nature” and points out it “causes a serious leakage of vital energy” and “drains … vital energy.”[25]

Observing thoughts and not identifying

Both authors insist this identification with habitual thinking must be overcome through self-observation. You must “begin to be aware through self-observation that inner talking is going on in you” and “observe it and notice what this inner talking is saying,” writes Nicoll. “Now when you observe a thought, you are not identified with it” he also explains.[26] Tolle also directs readers to “observe your mind” and “start listening to the voice in your head” and “pay particular attention to any repetitive thought patterns”—also calling this “watching the thinker”. “As you listen to the thought…. you are no longer energizing the mind through identification with it.”[27]

We are not our thoughts

Ultimately, we should come to recognise that our thoughts are not who we are. “You are not your thoughts,” writes Nicoll;[28] “You are not your mind,” or “thought processes,” states Tolle.[29] We’ll examine how self-observation is said to break identification with thoughts and inner states in more detail in the next section.

Overcoming Identification: Being the Observer of Inner States

Self-observation is presented as the means to address identification—a major mechanism Gurdjieff points to as keeping us asleep in daily life, that is, in a state lacking awareness, where most thoughts, feelings and actions are habitual, automatic and unconscious.[30] To really understand self-observation it is necessary to grasp this concept, which is heavily emphasised in both Nicoll and Tolle’s writings.

To “identify”, as it’s meant in the Fourth Way, is to lose your sense of identity in anything not your real self. What we identify with can change from moment-to-moment and includes our activities and “transient thoughts, moods and feelings.” People tend to identify with whatever absorbs their attention at a given moment.[31]

Nicoll writes much about psychological identification with changing inner states, thoughts, and emotions and reactions. To identify with these means to wrongly take each one to be you. Whenever you identify with an inner state it “will be what you are at that moment,” he explains.[32] Unless we observe our states, we tend to be automatically carried along by them and cannot see it, since we cannot distinguish between them and us. One’s life is then shaped by inner states unconsciously, often for the worse.[33]

Identification produces a lack of inner freedom, Nicoll reiterates, and this is its main problem: it puts us at the mercy of whatever we identify with. If we identify with a negative emotion or thought, for example, we remain under its power. In addition to any inner misery it brings or adverse effects it causes outwardly, it also drains our energy.[34]

Self-observation is employed to see the mechanics of identification in action, giving one the option to “separate internally” from states one would otherwise identify with automatically when inner awareness is absent.

“Now the practice of self-observation in the Work is to make us aware of where we are psychologically at any moment and eventually to shift our position…. Where we are psychologically at any moment is what we are at that moment, unless we are aware of it and separate internally from it. If you identify with all your inner states, with your negative emotions and dreary thoughts and so on, as people do in life if they are quite asleep, then where you are psychologically will be what you are at that moment. You will be your state at that time.”[35]

If we stop identifying with a negative state, Nicoll tells us, we reduce its power, create the possibility of acting consciously instead, and conserve and even gain force or energy. In his words, “being identified means not being conscious” and “to act consciously would mean to act without identifying.” This is “a new way of living—of living consciously inside yourself instead of mechanically” throughout daily life. And this is done via self-awareness and self-observation.[36] Only by observing what you would ordinarily identify with internally, Nicoll asserts, can you consciously separate from it within—that is, no longer feel it to be you.

“Ordinarily we are identified with everything that takes place inside us—with every thought, mood, desire, and so on. Self-observation in the Work-sense is to separate Observing ‘I’ from what is observed in oneself. For instance, you can observe the emotion of the beginning of anger. You can observe the thoughts connected with it. If your consciousness of the feeling of ‘I’ is stronger in observing ‘I’ than in what it observes, then your anger and the thoughts accompanying it will not have full power over you. The whole inner event may die away.”[37]

So becoming aware and inwardly separating from what Gurdjieff calls “unconscious involuntary personal manifestations”[38] is a primary objective of self-observation. And this idea is a central thrust in Nicoll’s and Tolle’s writings, and is particularly emphasised with negative states.

In both sources, one is repeatedly told to observe habitual thoughts, emotions and reactions without identifying with them, that is, without taking them to be ourselves. Our sense of self should be in the act of observing, not in the inner states observed. When self-observation is done rightly, the usual process of identification is thwarted: our sense of self shifts from inner states, thoughts and emotions to the observing consciousness watching them. By this act, one sees directly that inner states are distinct from one’s consciousness—which now can watch inner states without falling under their spell.

This is what it means to “non-identify” in Fourth Way terms. Tolle calls it “disidentifying,” and, as you might expect, the meaning is the same. This non-identification or disidentification, brought about by self-observation, is portrayed as absolutely integral to inner transformation in both sources.

Here is a summary of corresponding themes the authors convey when discussing the central concept of identification and using self-observation to overcome it:

- Self-observation counteracts our typical unconscious identification with transient inner states: otherwise we continually lose our sense or feeling of “I” or “self” in our thoughts or emotions to such an extent that they “become” us or we “become” them.

- Whatever inner factor we identify with takes our energy and exerts power over us, but we can prevent this and take force back by observing and ceasing to identify with it—and its power decreases in turn.

- Through self-observation, a sense of standing back or apart from our inner states emerges.

- We become “two” or see that we are “two”: we realise there is an observing consciousness, distinct from any momentary psychological content we can observe.

- We shift our sense or feeling of “I” or “self” increasingly to this observing consciousness, recognising observable psychic content as transient or false.

- Nicoll calls this observing consciousness “Observing I.” Tolle calls it the “Observing Presence” among other terms. Both describe it as a “silent witness.”

- Consciousness exists beyond all psychic content and so continues existing in its absence.

- In the process of shifting one’s sense of I or self to this observing consciousness, you also withdraw it from all that you are not.

- This includes not just transient thoughts and states but our overarching egotistical “false self”—a fictitious identity that “possesses” us. (Nicoll calls it the “false personality” and “imaginary I” while Tolle typically calls it the ego)

- By observing this false self we stop identifying with it and begin to break free from it.

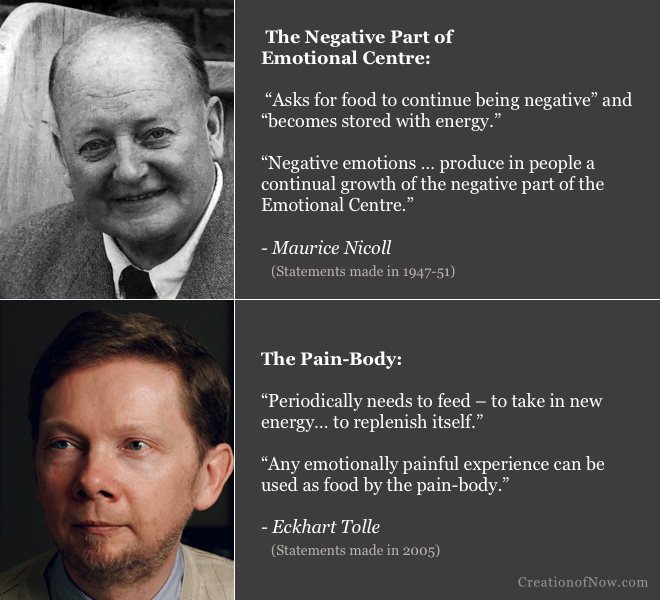

- Self-observation and non-identification is also used to reduce the psychological pain or suffering accrued and carried within us, and the factor that expresses our negative emotions.

- In Nicoll’s case, the “time-body” stores our accrued negativity and the “negative part of the emotional centre” expresses it; in Tolle’s case the “pain-body” does both.

- Ultimately, self-observation is used to cease identifying with any negative inner factor and thereby overcome it, and this underpins the whole process of inner transformation.

- Nicoll uses the term “non-identification” to describe this process; Tolle calls it “disidentification.”

I’ll now examine the similar ways the authors present these ideas in detail.

Misplacing the sense of “I” or “Self” and becoming inner states

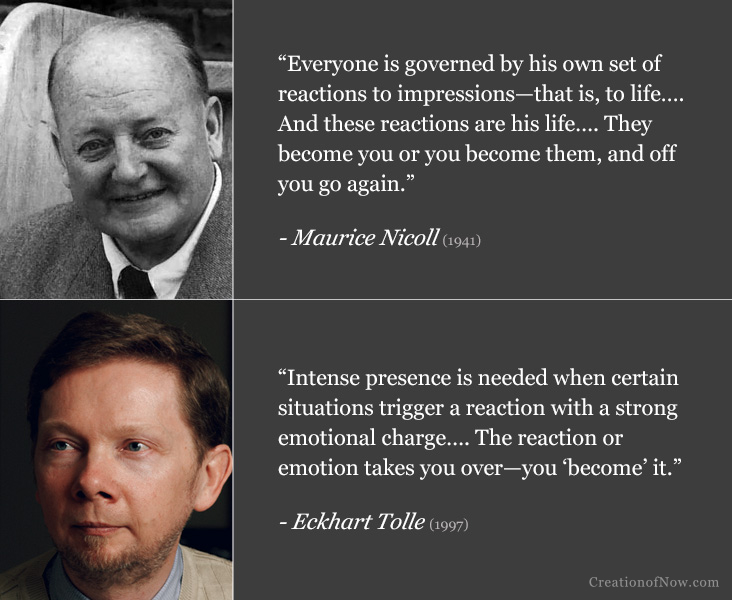

Nicoll and Tolle suggest that identification happens by wrongly transferring our feeling or sense of “I” or “self” into inner states, thoughts, emotions and opinions or mental positions—which are not really us. Our identity then merges with these to such an extent that, for that moment at least, we “become” our state or it “becomes” us. And this is typical for most people much of the time.

For example, Nicoll maintains that we identify with thoughts and emotions by putting “the feeling of ‘I’” or “sense of ‘I’” into them. By taking them as “I” we “fasten them” to ourselves, combine with them and cannot see them as separate. If you identify with a negative state then “you are your state” at that moment, he tells us, as “whatever you identify with you become”. Likewise if you identify with thoughts they “become you.” [39]

Tolle similarly suggests that we have become identified with thoughts and emotions by investing them “with a sense of I, a sense of self”. When you identify with an emotion, he tells us, then at that time it “becomes ‘you’”. [40]

Identification can happen with opinions too—“the feeling of ‘I’” can become fastened to an opinion we hold, according to Nicoll.[41] Tolle also agrees we invest our mental positions with a “sense of self” in our typical “mind-identified state”.[42]

Gaining and Losing Energy

We’ve already touched upon how identification is said to cause a loss of force or vital energy in relation to compulsive thinking, but the authors also claim that whatever inner factor we identify with somehow gains our force or can be energised by the process, and we, in turn, become its slave. Yet we gain back force or energy if we cease identifying through self-observation.[43]

When we do identify with something within, Nicoll writes, it “has power over us” and we “lose force to it.” “The more often we identify with something, the more we are slaves to it,” he explains. “Force is taken away” from us by identifying and “unconscious action” results, but through self-observation and non-identifying, we take force back and can “act consciously” instead. By observing thoughts and emotions they “will not have full power over you.” [44]

In a similar vein, Tolle conveys that by being “unconsciously identified” with the mind “you are its slave” and it’s “as if you were possessed without knowing it”. You energize the mind through identification with compulsive thoughts, he suggests, but a thought “loses its power over you” when you stop identifying with it—by consciously witnessing or observing it. This withdraws energy from the mind.[45]

Standing Apart from Inner States

In describing the detachment, or separation, from inner states, thoughts or emotions gained by observing them, the authors relate how a sense of standing apart from them emerges, or should emerge. Tolle speaks of “standing back” from a thought to look at it.[46] Nicoll writes of “standing outside” a state and looking at it “independent of it”:

“When you say: “I am feeling negative,” you are not observing yourself. You are your state. You are identified with your state. There is nothing distinct in you that is standing outside your state, something that does not feel your state, something that is independent of it, and is looking at it, something that has a quite different feeling from your state.”[47]

So to really observe an inner state you must be “standing outside” it and “looking at it,” otherwise you will still be “identified with your state.” Nicoll also writes how one must “step back” and “separate” from an “I” that is not really you—to be “standing behind” it in order to “watch it.” In this way, one gains a new conscious perspective whereby you “step behind the Personality-Machine and see it … no longer as you.”[48]

Describing his first major experience of “dis-identification”, Tolle similarly describes “standing back” from a thought and “looking at that thought.” Then “a dis-identification happened” from his false fictitious self. He also describes in broader terms the importance of “standing back” from thoughts and emotions by having “the ability to observe” and “to ‘watch’” them without “being identified” or “trapped in them.”

“There was a “standing back” from the thought and looking at that thought…. At that moment a dis-identification happened, “I” consciousness withdrew from its identification with the self, the mind-made fictitious entity.”[49]

“So there arises the ability suddenly to observe what the mind is doing, to observe thought processes, to become aware of repetitive thought patterns without being trapped in them, without being completely “in them.” So there is a “standing back.” It is the ability to observe what the mind is doing, and … to observe an emotion…. The ability to “watch” that without being identified.” [50]

In these examples, we can see that a sense of standing or stepping back from one’s habitual psychological states emerges from the inner act of observing them. One’s sense of identity shifts from being immersed in inner states, thoughts or emotions—that is, from being identified with them—to a perspective beyond them and “looking at” them. This idea is explored in depth in the authors work.

Thus self-observation brings a shift in consciousness where one’s sense of identity and perspective is no longer bound up in inner states. We’ll now look more closely at the authors describing this, and how it foils the usual process of identification.

Becoming “Two”: The Distinction between Observer and Observed

By inwardly stepping or standing back from inner states, one comes to see that they are not “one” but “two” the authors say. That is, we see that there are two main aspects of ourselves. We establish or recognise the presence of that which observes, as distinct from that which can be observed. It is only through the act of self-observation that one really sees the distinction between these two aspects.

By doing or experiencing this, the observing consciousness is recognised as real and fundamental, the basis for inner growth or awakening, while the fluctuating psychological content being observed is seen as not who we fundamentally are. We are said to recognise this fact through the very act of observation itself, by which, as we have seen, one’s sense of identity shifts from being tied to inner states, thoughts and emotions to being an independent observer existing beyond them. Both suggest this inner shift is absolutely necessary for inner transformation, as one cannot inwardly change without seeing, and ceasing to identify with, what they are not.

For example, Nicoll writes that you must stop taking yourself “as one” and instead, through self-observation, “become two” or “divide yourself into two”, which is essential to stop “identifying” and enable inner change. He explains that a person “must divide himself into IT and Observing ‘I’” or “an observing side and an observed side”. When a person really “begins to observe himself” “he will then, at that moment, become two” he explains; otherwise one remains in a state of identification with their inner states from which it is “impossible to change”.[51]

Through self-observation, Nicoll tells us, you “shift the centre of gravity of consciousness by becoming conscious of what you were not previously conscious of” within you, and, in this way, increasingly “feel the sense of ‘I’ in Observing ‘I’ and not in the observed side” of your psychology. He also explains why we cannot change without doing this. Having the “feeling of ‘I’” in any negative thought, feeling or inner state “will increase the strength and power” it has over you, he maintains. But by observing an inner state you “take the feeling of ‘I’ out of it” and it will “move away” and “pass … into the distance” internally, and one begins to gain a certain “inner freedom” from it. This idea of observing and not identifying with habitual inner states, and thus becoming “two, an observing side and observed side” is so vital he calls it the “keynote” of the teaching.[52]

“Self-observation carried out with the idea of not identifying with what you observe is the keynote of this system practically…. You know you must divide yourself into two, an observing side and an observed side—i.e. you must not identify with what you observe. This is the same as saying that you cannot change if you identify with everything that goes on in you—i.e. with every mood, every thought, every sensation, every form of imagination…. We have to take our psychology and all that lies in it objectively as we gradually observe it and gradually become more conscious of it.”[53]

Tolle, in his aforementioned account of watching a negative thought, relates how his observation gave rise to the question, “Am I one or two?” He soon saw the answer: “I saw that I was ‘two,’” he tells us—there was an “I” or “’I’ consciousness” and a “mind-made fictitious entity” behind the thought he was observing. He realised “only one of them is real”— the consciousness “looking at … the structure of that thought.” “At that moment a dis-identification happened,” he writes. He presents this experience as crucial to his own self-realisation.[54]

Similar to Nicoll, Tolle explains that through conscious observation one’s “sense of I” shifts from “thoughts, emotions and reactions” to “the conscious Presence that witnesses those states”. As you stop identifying with these inner states, you then undergo “a shift” in your “sense of self” to being the “observing presence”’ of your thoughts and emotions—and no longer feel mental or emotional states to be who you are. [55]

“And then you can observe a reaction, a mental or emotional reaction. Anger arises. The anger may still be there, but there is the observing “presence” which is the alertness in the background that watches the anger. So there is no longer a “self” in [the anger].”[56]

So we can see, in both cases, that seeing the distinction, psychologically, between what observes and what can be observed is essential to inner change—and self-observation is the lynchpin.

Being the Observing Consciousness

Thus on seeing that one is “two”, one withdraws or separates their sense of I or self from what is observed in their psychology and feels their sense of self in conscious observation instead.

But if the observable content of our psyche isn’t us, who or what is observing? In both cases, the authors attribute this observation to our consciousness, or an aspect of it, which exists beyond any psychological states.

They convey that consciousness is distinct from any psychological “content” such as thoughts and emotions. It allows one to be aware of such content, yet exists beyond it. Nicoll points out that “consciousness can exist without any content”[57] while Tolle points out that “thought cannot exist without consciousness, but consciousness does not need thought” and exists “behind the content of your mind”.[58]

The names given to this observing consciousness have been mentioned already. Nicoll typically uses the term “Observing I” to denote it, while Tolle calls it your “observing presence,” “conscious presence” or similar descriptors such as “the observer”, “the one who observes”, “witnessing presence”, “the watcher” or “the witness” etc. As we’ve seen, both describe it perceiving through awareness itself—a “silent witness” of what happens within—and its “power of self-observation” increases the more we use it. They also suggest that as it does grow stronger or increase, the power of the unconscious psychic content it observes decreases commensurately.

The authors suggest this observing consciousness is brought into action by the very act of observation itself. And once it is “present” it observes independent of the psychic content it sees. As discussed, it is the very act of self-observation that shifts our sense of identity from thoughts and emotions to this observing consciousness that watches them, and, in this way, breaks the usual identification with inner states. But we are not left rootless by this non-identification but, rather, feel ourselves to be something much more than anything observed—as being what Nicoll, in one instance, calls “the broader and deeper consciousness”[59] and Tolle describes as “pure consciousness beyond form.”[60]

This is not presented as an abstract philosophical notion, but a perceptual reality we can practically experience when we really observe ourselves. And this inner withdrawal of consciousness from psychological states, we are told, is the starting point from which the awakening process really proceeds.

Since this idea is presented as being so fundamental to any inner development or awakening, it is worthwhile showing some fuller examples of the authors expressing this. Here are some cases of Nicoll discussing this notion. He generally refers to this observing consciousness as Observing ‘I’—coming forth by the act of self-observation:

“Internal observation of oneself has to be a conscious act…. The impressions gained from self-observation are … from an internal sense given but not used, a silent witness in myself, a spectator of what goes on in me, into which I must put more and more consciousness, more and more my feeling of I, by withdrawing it (tediously, with trouble), from what it observes. A gradual concentration of consciousness and the feeling of I begins then at this point, which then becomes Observing I in a practical sense, as a practical experience.”[61]

“Self-Observation begins with the establishing of Observing ‘I’ in your own inner world. Observing ‘I’ is not identified with what it observes…. If you can observe your thoughts and worries, then you establish the starting-point of the Work in yourself. It is this observing side that is the new point of growth in you. So try to feel the sense of ‘I’ in Observing ‘I’ and not in the observed side [of your psychology]. Try to be conscious in Observing I.”[62]

“To become more conscious of oneself it is necessary that the consciousness of Observing ‘I’ must increase. The Observing ‘I’ is a part of consciousness in us not turned outwards via the senses but inwards towards our being…. This point of consciousness exists in everybody but remains as a rule totally undeveloped…. The Work can increase it and is designed to do so.”[63]

“Ordinarily we are identified with everything that takes place inside us—with every thought, mood, desire, and so on. Self-observation in the Work-sense is to separate Observing ‘I’ from what is observed in oneself.”[64]

“Self-observation is an act of attention directed inwards—to what is going on in you. The attention must be active—that is, directed…. The attention comes from the observing side, whereas the thoughts and emotions belong to the observed side in yourself…. The observing side, or Observing ‘I’, stands interior to, or above, the observed side.”[65]

“When you are able to use Observing I properly, you then have a point of consciousness that is independent of your moods. This point of consciousness is above your moods. It observes them from above. It does not become submerged in them. If you observe the mood going on in you, you are not it. You are not identified with it…. If you do not practise self-observation, you will never reach this stage.” [66]

“Can you see that an increase of consciousness, which is the goal of the Work, and which begins by making yourself more conscious of yourself to yourself by self-observation, would lead to an entirely different life? … Once we see for ourselves a thing recurring in ourselves through the inner sense of self-observation, we are gradually freed, gradually made less and less under its power. Why?—through the increase of consciousness. All increase of consciousness renders mechanical behaviour less dominating.”[67]

And here is Tolle expressing comparable notions, referring to this observing consciousness as the “observing presence”, “witnessing presence” or “conscious presence” which becomes present through self-observation.

“Through self-observation, more presence comes into your life automatically. … Whenever you are able to observe your mind, you are no longer trapped in it. Another factor has come in, something that is not of the mind: the witnessing presence.”[68]

“Watch the thought, feel the emotion, observe the reaction. … You will then feel something more powerful than any of those things that you observe: the still, observing presence itself behind the content of your mind, the silent watcher.”[69]

“Stay present, and continue to be the observer of what is happening inside you. Become aware not only of the emotional pain but also of “the one who observes,” the silent watcher. This is the power of the Now, the power of your own conscious presence.”[70]

“The beginning of spiritual awakening is the realization that “I am not my thoughts,” and “I am not my emotions.” So there arises the ability suddenly to observe what the mind is doing, to observe thought processes, to become aware of repetitive thought patterns without being trapped in them, without being completely “in them.” So there is a “standing back.” It is the ability to observe what the mind is doing, and the ability also to observe an emotion…. The ability to “watch” that without being identified. That means your whole sense of identity shifts from being the thought or the emotion to being the “observing presence.’”[71]

“The thoughts, emotions, or reactions are recognized, and in the moment of recognizing, disidentification happens automatically…. Before you were the thoughts, emotions and reactions; now you are … the conscious Presence that witnesses those states.”[72]

“Can you now see the deeper and wider significance of becoming present as the watcher of your mind? Whenever you watch the mind, you withdraw consciousness from mind forms, and it then becomes what we call the watcher or the witness. Consequently, the watcher — pure consciousness beyond form — becomes stronger, and the mental formations become weaker.”[73]

Separating from the False

As we have seen, by shifting one’s “sense of I” or “sense of identity” into conscious observation, one simultaneously withdraws or separates it from any thought or emotion one had previously identified with in that moment. For this to occur, one must actually see and feel that what they observe in their psyche is not who they fundamentally are— but that it is, as Nicoll puts it, “not I,”[74] or as Tolle has put it, “not self.”[75]

I have discussed this idea at length with respect to transient inner states, emotions and thoughts, but the idea of separating from the false goes deeper than that. According to both authors, each of us is possessed by—or identified with—a “false self” comprised of mental images or pictures of who we imagine ourselves to be. While inner states change, this underlying illusion of oneself typically remains entrenched. Even though it persists beyond any particular thought or emotion that arises, it is nevertheless intrinsically linked to them.

This is because so much of our automatic mental-emotional states and reactions arise to defend or maintain this fiction of who we think we are—both internally to ourselves and externally to others. Tolle uses the common term “ego” to describe this “false self” created by mind identification,[76] while Nicoll uses the Fourth Way terms “False Personality” or “Imaginary I” to denote this egotistical false self.[77] In both cases, it is described as a fictitious self-creation. Through self-observation, one is said to gain a certain separation and inner freedom not only from involuntary inner states, but one’s underlying false identity subsisting beneath them. And, by doing so, one becomes more and more in touch with their real self.

This is quite a deep idea. Much more can be said about the comparable ways Nicoll and Tolle conceive of the false self and contrast it with a person’s real self, which Nicoll often calls “Essence” and “Real I”[78] and Tolle has called “essence identity”[79] and “Deep I”.[80] But that’s beyond the scope of this article; I’ve examined this topic in depth in another article: “Essence, Personality and the False Self.” Here, it is only necessary to have some idea what these concepts mean.

For now, I’ll provide some examples of Nicoll presenting this idea, which gives more than enough of an overview.

“Not one of us, as we are mechanically in life, has his or her centre of gravity in Real I. We have it in False Personality, in Imaginary ‘I’, in a fiction of ourselves that we have to keep going. So each of us has to do all sorts of things in order to keep up this imaginary self, the False Self, this self that is not really deeply us, in order that we, as it were, do not lose face—or, in fact, lose all sense of ourselves.”[81]

“The False Personality, always pre-occupied with … whether a good impression is being made and appearances kept up, causes a strain in Being. It is as if a man kept on standing on his toes and did not understand why he felt exhausted. All the time he is keeping something up which is not himself—something imaginary—something which does not fit him. And this happens with everyone. If we had no False Personality all this anxiety and nervousness which all secretly feel about themselves, whether they admit it or not, would vanish. Not only would our relationship to others change, but our relationship to ourselves.”[82]

“Now, since we are so much centred in the False Personality, from which we derive an imaginary feeling of I, or Imaginary ‘I’, it is necessary, in order to begin to move towards Real I, to separate our consciousness from False Personality. This means that you must shift the centre of gravity of consciousness by becoming conscious of what you were not previously conscious of. This can only be done by observing the False Personality in oneself. This leads to a gradual displacement of the previous psychological centre of gravity of I.”[83]

“Now, if you can separate by observation of it from False Personality—which means that you can see it consciously and so are distinct from it (since what you are not conscious of in yourself will control you, because you are identified with it)—if you can separate from the False Personality, then you will change internally and the whole world and all life will change for you correspondingly. Why? Because an increase of consciousness has taken place. This Work is about increasing consciousness—firstly of you—of what you are. If you become more and more conscious of False Personality … then the broader and deeper consciousness will release you from a negative and small-minded, egotistical bundle of personal reactions, full of self-fears and hopes, foolish ambitions, daily lying, unnecessary unhappiness, stupid judgments, false pride, imbecile vanity, and all the rest. In short, you will move away from this spurious person you have taken yourself as and served as a slave—that is, False Personality—and begin to approach the great test for Man and Woman as regards their inner sincerity and integrity … that if passed leads to the Real I.”[84]

“This release from oneself, this release from Imaginary ‘I’, from the pictures one has had of oneself, from False Personality, is the greatest good one can do to oneself, and it involves the whole of the Work, its ideas, its practical teaching.”[85]

The key points I want to emphasise and explore here are:

- Both Nicoll and Tolle suggest a shift in consciousness away from one’s overarching false identity is necessary. They refer to separating or withdrawing from it directly, as well as the various unconscious thoughts and emotions associated with it.

- Self-observation—by whatever term it is designated—is presented as the means to do this.

Nicoll makes clear that we “cannot begin to change” until we recognise what is “not I” and separate from it—that is, no longer identify with it—because anything you identify with “has power over you and makes you serve it.” And this is particularly true of the “artificial person” and illusory “feeling of oneself” we “cling to” which “possesses us without our seeing it.” We are “centred in the False Personality, from which we derive an imaginary feeling of I,” he writes, and must “shift the centre of gravity of consciousness” and “separate our consciousness” away from it by becoming conscious of this aspect we were previously unconscious of, and “feel the sense of ‘I’ in the observing side and not in the observed side” of ourselves. Seeing “one’s False Personality is one of the most important starting-points of self-observation,” he writes, “because unless one can separate from this fiction of oneself nothing can shift internally.” If you do persistently observe and separate your “feeling of I” from the False Personality, he suggests, then gradually “the broader and deeper consciousness will release you” from it.[86]

Tolle likewise explains that identification leads to “failing to recognise” the ego or “possessing entity” as “not self” or as a “false sense of self” and because of this people become “possessed without knowing it” and are then like a “slave” to their ego or “egoic mind”. Tolle describes Ego as “a false self, created by unconscious identification with the mind”—“a conglomeration of recurring thought forms and conditioned mental-emotional patterns that are invested with a sense of I, a sense of self.” But “the beginning of freedom”, he writes, comes from realizing “you are not the possessing entity” and observing it—then “you know who you are not.” And in “the moment you start watching” it a “higher level of consciousness becomes activated,” he writes. Thus, “when you observe the ego in yourself you are beginning to go beyond it.”[87]

There is one more aspect to briefly mention here. In a previous article, I discussed Nicoll’s presentation of the “Time Body” storing up psychological suffering and the “negative part of the emotional centre” which develops from childhood to express unnatural emotional negativity. I highlighted the similarities these notions share with Tolle’s idea of the “pain-body” in which both concepts converge—the pain-body, according to Tolle, both stores emotional pain and negativity and also expresses it. In both cases, the negative emotional part and pain-body are closely related to our false self: they are the psychic mechanism through which negative emotions are expressed, often in defence of our false identity.

I don’t wish to revisit these concepts in detail, but only mention that self-observation remains the primary practice to deal with these additional psychic factors.[88] By observing emotional negativity, one dis-identifies with it. This is said to clear out the accumulated suffering we carry within us, reduce the power of the negative emotional part or pain-body respectively—through which this negativity manifests— and to eventually eradicate these aspects in us entirely.

Ultimately, self-observation is presented as the primary means to deal with any unconscious psychological factors, whether compulsive thoughts, negative emotions, accumulated pain or suffering or the false self.

A point of difference is that Nicoll is quite insistent that dissolving the false personality and eradicating negative emotions requires a long and gradual process of inner work; Tolle tends to downplay notions of time and difficulties involved and even suggests a complete transformation can happen near-instantly in “some rare cases” with “rare beings”.

The reader can refer to my articles, “Eckhart Tolle’s “Pain-Body”: A Deep Dive into its Hidden History” and “The Creation of Now: How Fourth Way Authors Sparked a Revolution of the Present Moment” which include some discussions of their similarities and differences on these points.

Non-identifying or disidentifying – A Summary

The previous sections have provided an in-depth comparison of how the authors describe overcoming psychological identification through the practice of self-observation. To summarise, Nicoll and Tolle convey that:

- In the act of self-observation, one inwardly “stands” back or apart from the transient inner states that are usually identified with.

- One sees they are “two”—one aspect is the observing consciousness, which is real, and the other is made up of transient emotions and thoughts connected with a false self.

- At that moment, one separates or withdraws their sense of identity from the false or transient in them, and feels their deeper sense of self as being the observing consciousness .

- One then is the “observing I” or “observing presence”—the “silent witness” independent of psychological content observed.

- One is no longer identified with psychological content, and can consciously observe it with detachment, without falling under its power.

This, in essence, is what Nicoll and Tolle mean when they use the terms “non-identify” and “disidentify” respectively. These phrases denote the process of using self-observation to cease psychological identification in the present moment, which both present as integral to inner transformation. It is also something to return to again and again, as, at any moment—at least for most people—one can fall back into an unconscious state of identification and one must “step back” from their immersion in inner states again and again.

So to round off this article, I’ll highlight some examples of the authors using variations of their preferred terms for this important inner process—non-identification and disidentification. [89]

In the excerpts below, Nicoll points out that non-identifying is essential for inner change and writes of non-identifying with thoughts, moods and feelings. He indicates that “to non-identify” is to “take all feeling of ‘I’ out of a thing” you observe, recognising it as “not I” and “separating” from it. The term “inner separation” is also used to describe this. In one instance he explains this with reference to a “typical chain of associations or thoughts”—one can change it if they observe it and do not “say ‘I’ to it” or believe it is themselves thinking it.[90]

“In the Work we all have a very powerful instrument in us called non-identifying…. If a man is always identified with his inner state of the moment, with his thoughts and his moods, etc. then he cannot change. For a man to shift from the position he is in …. he must be able to observe his state.”[91]

“If you can realize practically—that is, by experience—that you can be passive to your thoughts by non-identifying with them, you have already reached a definite stage of work… But if you take yourself as one you will never get to this point. You will remain stuck in the illusion that all your thoughts as well as all your feelings and moods are you.”[92]

“In regard to… associative thinking, one must observe some typical chain of associations or thoughts that one wishes to change and become passive to it. That means, one must not say ‘I to it, nor believe it is ‘I’ thinking it, but that it is the machine of associations thinking it. It is thinking it, not I. To non-identify, you must take all feeling of ‘I’ out of a thing. But as you know, for a very long time we take every psychic happening in us, that is, every thought and feeling, as ‘I’—as oneself— as me. And this attitude to our inner psychic world is as foolish as a corresponding attitude to the external world by our senses. I do not take the table as me, as I. Nor need I take my thoughts in that way.”[93]

“The method of this Work is through non-identifying with yourself. You must learn not to identify with yourself—by observing yourself and separating.”[94]

“Inner separation means the power of not merely saying: “This is not I”, but ultimately of actually perceiving it for oneself—perceiving that it is true, that “this is not I”, not merely thinking it is so or trying to persuade oneself it is, or saying this is what the Work says.”[95]

“We have to practise non-identifying in the midst of the happenings of life … we have to notice and separate ourselves from our negative emotions in the midst of all hurts and smarts in daily life.”[96]

Tolle similarly presents disidentification as essential; in fact he calls it “the single most vital step on your journey toward enlightenment.” He explains that to disidentify one must witness or be “the silent watcher” of their “thoughts and behaviour” without “investing” what is observed with “selfness”. He often emphasises this idea with reference to thoughts or, as in one instance cited, “repetitive patterns of your mind”.[97]

“The moment you become aware of a negative state within yourself, it does not mean you have failed. It means that you have succeeded. Until that awareness happens, there is identification with inner states, and such identification is ego. With awareness comes disidentification from thoughts, emotions, and reactions. The thoughts, emotions, or reactions are recognized, and in the moment of recognizing, disidentification happens automatically. Your sense of self, of who you are, then undergoes a shift: Before you were the thoughts, emotions and reactions; now you are the awareness, the conscious Presence that witnesses those states.”[98]

“To disidentify from the pain-body is to bring presence into the pain and thus transmute it. To disidentify from thinking is to be the silent watcher of your thoughts and behavior, especially the repetitive patterns of your mind and the roles played by the ego. If you stop investing it with “selfness,” the mind loses its compulsive quality.”[99]

“So the single most vital step on your journey toward enlightenment is this: learn to disidentify from your mind.”[100]

“Some people never forget the first time they disidentified from their thoughts and thus briefly experienced the shift in identity from being the content of their mind to being the awareness in the background.”[101]

“And then suddenly there was a “standing back” from the thought and Looking at that thought, at the structure of that thought…. At that moment, a dis-identification happened. “I” consciousness withdrew from its identification with the self, the mind-made fictitious entity, the unhappy “little me” and its story.”[102]

“Watch out for any kind of defensiveness within yourself. What are you defending? An illusory identity, an image in your mind, a fictitious entity. By making this pattern conscious, by witnessing it, you disidentify from it.”[103]

I should briefly note that Tolle’s use of “disidentify” as opposed to “non-identify” is not new in this context. The same term appears in earlier sources presenting Fourth Way ideas, including books on the subject by transpersonal psychologist Charles T. Tart, whose work in this sphere I’ve briefly discussed in relation to Tolle’s before.[104]

Closing Comments

Maurice Nicoll and Eckhart Tolle both present self-observation as a fundamental spiritual practice for inner transformation. They make a number of similar points about why it is so important and how to approach it. Tolle often uses other phrases to refer to the same exercise, but many of its fundamentals are there nonetheless. They both emphasise that self-observation, and, importantly, the change in consciousness—the transcendence of identification—that comes from it, is the starting point for inner transformation or awakening.

The practice of self-observation, as approached by these authors, ultimately traces back most directly to Gurdjieff of course, but Nicoll’s presentation of it represents perhaps the most extensive body of writing on the subject among contemporary literary sources—certainly for the 20th century, and possibly to date. His expositions also incorporate unique insights that draw, at times, on other influences, such as Jungian psychology. His body of work has had a profound impact on later writers on the topic—most notably, I believe, Eckhart Tolle. This article has discussed a number of correspondences that support this assertion, highlighting commonalities in the emphasis of certain themes, advice given, and language used.

However, this is a premise I intend to explore further. Nicoll, as I’ve mentioned before, once wrote that self-observation is an “inexhaustible” topic. Perhaps not surprisingly then, there is more to be said about the lasting influence his in-depth consideration of this subject still carries.

In the next article of this series, I explore how the authors coincide in describing “the light of consciousness” being cast inwards via self-observation to produce inner-transformation.

Leave a Reply