Fusing Jung with Gurdjieff, Maurice Nicoll describes “the light of consciousness” transforming us via self-observation. Eckhart Tolle mirrors this approach.

Previously I showed how Eckhart Tolle, in his bestselling books, extensively mirrors key aspects of Maurice Nicoll’s formative approach to describing the practice of self-observation. Continuing this inquiry, I explore how Nicoll fused Jungian notions of confronting the unconscious with Fourth Way methodology to describe, in compelling, evocative language, how “the light of consciousness” is directed within through self-observation to transform “the darkness of unconsciousness” in the psyche. As we shall see, Tolle corresponds a great deal with Nicoll on this theme too, both descriptively and conceptually, using the same phrase, “the light of consciousness,” or close variations, in much the same way.

This is part two of an article series comparing corresponding ways Maurice Nicoll and Eckhart Tolle present self-observation—a practice both uphold as integral to inner transformation. I believe the combined evidence presented here, showing substantial similarities between them, suggests Nicoll may have had a significant under-recognised influence on Tolle’s work. If you’ve just landed here, you may want to read the introduction and part 1 for further background before continuing.

Harnessing “the light of consciousness” through self-observation is a key theme in both authors work.

Before I dive into comprehensive comparisons of Nicoll’s and Tolle’s work on this theme, I provide some background context first. What follows is a brief historico-cultural overview of how the phrase “the light of consciousness” is used to express the transcendent, illuminating nature of consciousness in contemporary vernacular—in which “consciousness,” as a term, has been increasingly spiritualised.

I then show how Nicoll drew inspiration from both Jung and the Fourth Way when imparting the latter system’s self-knowledge teachings—namely, when describing how practicing self-observation harnesses and directs “the light of consciousness” inwards to bring about change in the psyche. Understanding this unique fusion of influences in Nicoll’s writing helps to appreciate how novel and distinctive it was in its time and recognise its continued influence today.

If you wish to jump straight into my comparative analysis of Nicoll’s and Tolle’s work on this theme, however, then select this link to skip ahead to the “summary of correspondences” section and go from there. Otherwise, read on.

The light of consciousness as transcendent

Maurice Nicoll often discusses “the light of consciousnesses” in his Psychological Commentaries[1]

This language, used outside of orthodox religion and science of course, is sometimes employed to express in modern terms an ancient view that all living beings are divine sparks from the same source. Consciousness may designate the spark of light in us personally—our “soul”—or the all-pervasive source behind everything, depending on the context.

There is also a certain phrase, “the light of consciousness,” used in various ways to express the link between consciousness and light, whether human consciousness and its level of development or a higher divine consciousness. I’ve seen it used interchangeably with “the Self” (Atman) in recent English-language discussions of the Upanishads for example.[3]

The phrase “the light of consciousness” also appears in the field of analytical psychology founded by the highly influential 20th century thinker Carl Jung—part mystic and part scientist.[4] In one of his early dream visions, Jung recounts struggling against a forceful wind in a dark, fog-covered landscape while carrying a small flickering flame in his cupped hands. Looking behind, he saw a huge, shadowy figure following him. He recognised the “little light” as his consciousness, to be kept alight at all costs, and the ominous figure as his psychological “shadow”—an embodiment of the dark, unknown and often sinister side of himself, hidden in his unconscious, that holds greater power while it remains unseen and un-confronted. Such experiences shaped his understanding of human psychology and what he saw as an essential factor to its harmonious development—making the unconscious conscious.[5]

In a dream, Jung saw his consciousness as a flame flickering in his cupped hands.

In contemporary spiritual perspectives, whether New Age, transpersonal psychology, or modern interpretations of ancient traditions, a shared view seems to be that our conscious perception—the inner “light” of our self-awareness—is closely linked to light in a mystic or even mythic sense. Consciousness is understandably viewed as “light” because without the awareness it brings we could not perceive anything within or without. Darkness, ignorance and evil, on the other hand, are often described as forms of “unconsciousness” in this contemporary psychological language.

Ancient traditions certainly speak of forces of light and darkness, but this is often done cryptically, or presented on an epic or cosmic scale. It can be easy to view such accounts as somehow remote or fantastical—happening “out there” in supernatural realms beyond our reach or in some distant, mythic past. That is a domain of extraordinary heroes, saints, philosophers and gods it seems. It can all seem very far away from our daily lives.

Yet the idea that light and darkness are qualities living inside us, here and now, becomes more understandable when put into modern psychological terms. To speak of “consciousness” and “unconsciousness” takes metaphysics down to the fundamentals we can see and deal with personally here and now, by calling us to examine how we perceive, and what is going on within us. In this way, the confrontation between light and darkness is made tangible.

While there are a range of contemporary perspectives that use this dialect in a broader sense, in this article I’m looking at how “the light of consciousness” has been used to describe human consciousness perceiving and changing its unconscious psychology through the practice of self-observation specifically.

“The idea of using self-observation to bring about a conscious confrontation with unconsciousness is really brought to life in Nicoll’s major work…”

There is a little-known 20th-century author who articulated this idea decisively, bringing together relevant currents of western esotericism and modern psychology in a potent and influential way. If you’ve read my earlier articles, you’ll know I’m referring to Maurice Nicoll, the Jungian psychologist who became a Fourth Way teacher and wrote extensively about self-observation.

In the Fourth Way, self-observation is the primary self-knowledge practice to undertake a process of inner work where one struggles against detrimental factors operating mechanically or unconsciously within them in daily life.[6] G.I. Gurdjieff, who initiated this teaching in Russia in 1914, before he and P.D Ouspensky brought it to the West,[7] stated that this struggle produces the inner fire or “friction” that “will gradually transform [one’s] inner world into a single whole.”[8] He also connected this process, which involves the conservation and transmutation of one’s energies, with medieval alchemy.[9]

Something it shares with Jung’s approach—aside from linking psychological transformation to the symbolism of medieval alchemy, a connection Jung also made—is that both methods can be said to necessitate a struggle or confrontation with the unconscious.

The need to confront and transform, not ignore, “the world of darkness” within us is one of the primary thrusts of Jung’s view of psychological development, and an aspect he considered lacking in popular forms of contemporary western spirituality:

Filling the conscious mind with ideal conceptions is a characteristic feature of Western theosophy, but not the confrontation with the shadow and the world of darkness. One does not become enlightened by imagining figures of light, but by making the darkness conscious. The later procedure, however, is disagreeable and therefore not popular.[10]

The same critique cannot be levelled against the Fourth Way however—the inner work it engenders is all about facing the “inner darkness” or “unconsciousness” within us and destroying illusions about ourselves in the process—points Nicoll often emphasised. [11]

In developing his understanding of these parallel themes in both systems, Nicoll was uniquely placed to draw inspiration from both Jung and Fourth Way teachings when he taught the latter. However, the primary means or method to undertake this struggle or confrontation with one’s inner darkness is different in each system. Nicoll, who believed the Fourth Way offered a more complete system than Jung’s,[12] extolled “self-knowledge by the method of self-observation” as Gurdjieff had:[13]

But the object of the Work is to stir up a struggle in us, a struggle with this false contentment and complacency [about ourselves]. And what is the method used? The method is self-observation, whereby we gradually become more conscious of what is in us.[14]

By becoming more conscious of what is in us through self-observation we are “parted from the illusion of ourselves,” Nicoll tells us, but this then makes it possible to receive help from a higher level and change within. “When we observe what we are really like we make ourselves open to receive help—help that can really change us. Help cannot reach us while we are self-satisfied.” And becoming more conscious of ourselves starts with directing the light of consciousness impartially inwards, Nicoll maintains. Self-observation “is like a window to let in light”—the light of consciousness—which shines into our inner psychic life hidden in darkness:[15]

Now the object of the Work on its practical side is to let a ray of light into the inner darkness of ourselves, this not-perceived side. Light means consciousness. We have a dark side of ourselves, a side in darkness that we do not see…. What is the result of light? The result is the seeing of a part of the darkness and bringing it into consciousness. This is an extension of consciousness—an increase of consciousness.[16]

A distinguishing characteristic of self-observation is that it’s a present-moment practice: one observes and catches their psychic processes and habits in the act, red handed, as they are occurring. In that sense it shares some commonalities with the practice of mindfulness popularised later in the west. Analytical psychology, on the other hand, lays more emphasis on retrospective analysis—one looks back and reflects upon psychic processes, whether upon dreams or prior events, in past tense, with or without the help of an analyst.[17] Both approaches aim to gradually build up a more accurate picture of one’s psychic life. Yet an object of each—self-knowledge and inner change through bringing what is unconscious into the light of consciousness—shares that much in common at least, whatever else their differences philosophically and in practice.

The idea of using self-observation to bring about a conscious confrontation with unconsciousness is really brought to life in Nicoll’s major work, Psychological Commentaries on the Teaching of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky, published in the early 50s. More than any prior literary source at the time, he lays great emphasis on taking the “the light of consciousness” into our psychological darkness or unconsciousness through self-observation specifically. There are recurring references to the light of consciousness or close variations of the phrase, almost always in connection with this practice and the inner work it entails.

Maurice Nicoll (far right) with Gurdjieff (far left) in Paris in 1922. Nicoll’s wife and Madame Ouspensky, wife of P.D. Ouspensky, sit between.

Gurdjieff and Jung were contemporaries, and, quite independently it seems, used the phrase light of consciousness in reference to acquiring self-knowledge.[18] In Gurdjieff’s case, in the one recorded instance he employs the phrase in his early teaching, he explicitly applies it to the practice of self-observation. This practice, according to Gurdjieff, directs the light of consciousness onto psychic processes happening in darkness, shining a “ray of light” upon them:

“Self-observation brings man to the realization of the necessity for self-change. And in observing himself a man notices that self-observation itself brings about certain changes in his inner processes. He begins to understand that self-observation is an instrument of self-change, a means of awakening. By observing himself he throws, as it were, a ray of light onto his inner processes which have hitherto worked in complete darkness. And under the influence of this light the processes themselves begin to change. There are a great many chemical processes that can take place only in the absence of light. Exactly in the same way many psychic processes can take place only in the dark. Even a feeble light of consciousness is enough to change completely the character of a process, while it makes many of them altogether impossible. Our inner psychic processes (our inner alchemy) have much in common with those chemical processes in which light changes the character of the process and they are subject to analogous laws.”[19]

This is a brief point in Gurdjieff’s discourse, but in Nicoll’s commentaries this idea is enlarged, expanded, and made central; nevertheless, the foundation for much of what he writes can be traced to this formative passage. The language becomes more standardised and recurrent in Nicoll’s hands: references to “the light of consciousness” and bringing unconscious factors into this light through self-observation to “become conscious” of them is a recurrent theme. The connection between consciousness and light is repeatedly made. Indeed, at times Nicoll frames the process of self-observation in almost mythic terms as an epic struggle between light/consciousness and darkness/unconsciousness.

The “inner darkness” or “psychological darkness” or “darkness of unconsciousness” Nicoll describes encompasses all the habitual thoughts, feelings, reactions etc. occurring all the time beyond one’s conscious awareness, among other things. The light of consciousness turned inwardly on ourselves through self-observation, he maintains, can penetrate our illusions to uncover the “unobserved” “dark side” of one’s psyche and see what is actually occurring in us and “make it conscious.”[20] The following passage is a good example of Nicoll expressing the light versus darkness motif explicitly:

We know that the object of self-observation is to let the light of consciousness into what lies in darkness within us. We are unconscious of all that lies in darkness in us. Unconsciousness is darkness, and darkness is unconsciousness. The only remedy is consciousness, which is light. Light overcomes darkness…. We know that whatever we bring into the light of consciousness loses the power it has over us if it remains unconscious—that is, in our inner, unexplored darkness. Operating from our darkness it can have very great power and extraordinary fascination. What would be the object of conscious self-observation so that it is dragged into the light if it were not so? Yet, as I said, people do not see what is meant. They cannot connect light with consciousness, because the words are different. And for that reason they do not comprehend self-observation or what it is for. Unless we let the light of consciousness increasingly into ourselves, we cannot change. All that we are unconscious of within, all that lies in the darkness of unconsciousness in us, remains unchanged and as active as ever.[21]

Nicoll may have learned self-observation from Gurdjieff and Ouspensky, but the almost primordial overtones he sometimes couched it in—literally as a “struggle between Light and Darkness” —undoubtedly owes something to Jung, who looked at myths and dreams to deduce common archetypes of the psyche expressed via universal symbols. While Jung’s influence on Nicoll on this theme is often implicit, Nicoll does, in some cases, make explicit reference to Jung and his concept of the psychological shadow when discussing these ideas. He also connects the process of self-observation with heroic myths, describing it as “an advance inwards against an enemy” within us. In a latter lecture he refers to this enemy as the “Dragon of Darkness” that “only the hero, consciousness, can contend with.” “The hero lives, to begin with,” he suggests, in the inner perception “by which we can observe ourselves.” [22]

“In Nicoll’s hands, self-observation becomes the keystone for a primordial inner quest where consciousness is pitted against forces of darkness within”

In making these references, Nicoll shows familiarity with the idea of the monomyth, or hero’s journey, then gaining recognition through Joseph Campbell’s influential work, itself influenced by Jung. Nicoll obliquely connects this archetypal journey to the inner work of the Fourth Way. His point of difference, once again, is in making self-observation the practical starting point for embarking on this inward “journey of increasing consciousness.”[23]

However, it’s not just this unique fusion of influences coming together in Nicoll’s writing that adds depth and texture, but his own self-knowledge. Nicoll is clearly a true believer in self-observation and a dedicated practitioner of it, and draws much from his own experience. The overall effect is an account of the practice that is in turns more personal, practical and down-to-earth as well as more “epic,” with almost mythic overtones at times. That kind of touch was absent in earlier, typically drier, descriptions.

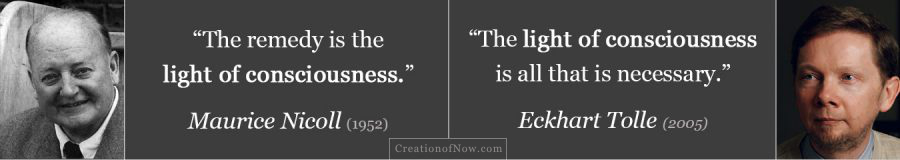

In Nicoll’s hands, self-observation becomes the keystone for a primordial inner quest where consciousness is pitted against forces of darkness within. The evocative language he employed remains influential upon latter-day descriptions of the practice. The recurrent phrase “the light of consciousness,” used 50 times in his commentaries, is a case in point.[24]

This brings us to the crux of this article. This is the second part of a series examining evidence that, I argue, indicates Nicoll may have influenced the most prominent contemporary spiritual author of our time, Eckhart Tolle, in how he presents self-observation.

…“the light of consciousness” has been invoked in other philosophies and methods, but Nicoll emphatically applied it to the practice of self-observation specifically.”

To reiterate, self-observation is the primary spiritual practice Tolle conveys. While he does actually call it by that name at times, he often refers to it by other interchangeable terms—such as being “the witnessing presence” or “the watcher” of “your thoughts and emotions.”[25] If we examine Tolle’s treatment of this subject, we find he also follows closely in Nicoll’s footsteps on this theme, making repeated references to the light of consciousness—or close variations of the phrase—when explaining self-observation, and calling for all unconsciousness—including the “pain-body”—to be brought into this light for inner transformation.[26]

While this phrase has permeated into wider cultural use in various contexts, what is most relevant here is its specific application to the practice of self-observation. As I pointed out earlier, “the light of consciousness” has been invoked in other philosophies and methods, but Nicoll emphatically applied it to the practice of self-observation specifically. This is an important distinction to keep in mind, as Tolle also uses the expression—and equivalent variants like “the light of your presence”—in the same context to express many of the same themes. It is this correspondence that I’m examining here.

I’ll now outline the many ways the authors correspond on this theme.

Summary of correspondences: Nicoll & Tolle on the light of consciousness

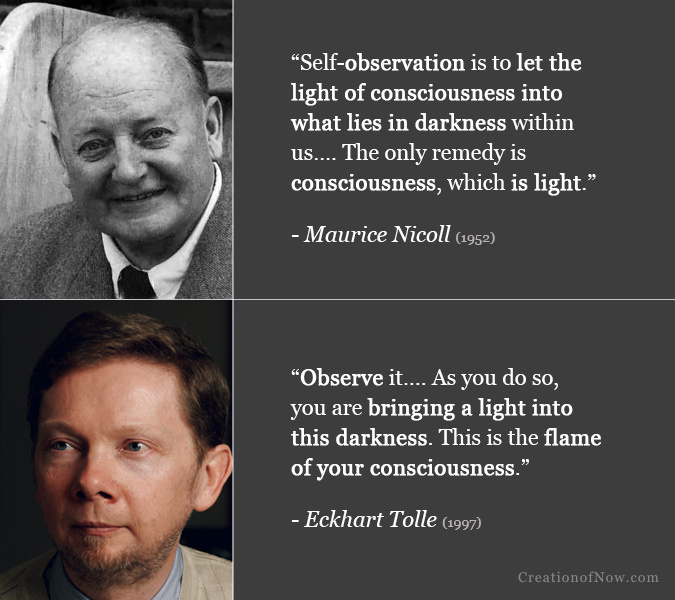

Both Nicoll and Tolle employ the phrase “the light of consciousness” repeatedly when describing self-observation. Essentially, both Maurice Nicoll and Eckhart Tolle see the light of consciousness or presence as being cast inwards—as a “ray” or “beam” of light— by the act of self-observation, as Gurdjieff had described. This light is said to make us conscious of unconscious processes operating in that moment and brings about a process of transformation—weakening, transmuting and eventually ultimately dissolving negative unconscious factors it illuminates. They make a number of similar points and employ comparable, distinctive phraseology in expressing these ideas.

Nicoll and Tolle often describe the transformative effects of “the light of consciousness” which is directed within via self-observation.

Broadly speaking, their similarities on this theme can be summarised in the following five points:

- Shining “the light of consciousnesses” within. The inward attention of self-observation is equated with “consciousness” and “light”. This light is also described as a “beam of observation” or “ray of light” (Nicoll) or “beam of light” (Tolle). Through conscious observation (or what Tolle also calls “presence”[27]) “the light of consciousness” illuminates, shines or is thrown upon what is happening unconsciously in one’s psyche in that moment.

- Bringing “unconsciousness” into the light to “make it conscious.” Both speak of the need to become conscious of one’s previously “unobserved” unconsciousness and “make it conscious” by directly observing any unconscious inner state in the light of consciousness, as it occurs. Both convey the need to bring what is unconscious “into the light” of consciousness by this method, or bring the light to it.

- The light of consciousness produces inner transformation. Both authors present the light of consciousness as the primary agent of inner change. Its active perception in self-observation allows us to stop identifying with inner states (an idea discussed in depth in a previous article) and can disempower and even dissolve negative unconscious content it sees. The observation/attention should be “continuous” (Nicoll) or “sustained” (Tolle), and there must be acceptance, not denial, of what is seen. This is described as a process of inner transmutation or transformation linked to “esoteric” alchemy. The authors differ markedly in conveying the rate of change possible—Tolle suggests it can in certain cases happen quickly, while Nicoll emphasises it is gradual.

- The light of consciousness/presence grows stronger. The light of consciousness / presence becomes brighter and stronger, increasing or growing in power as unconsciousness is diminished through being brought into its light by self-observation.

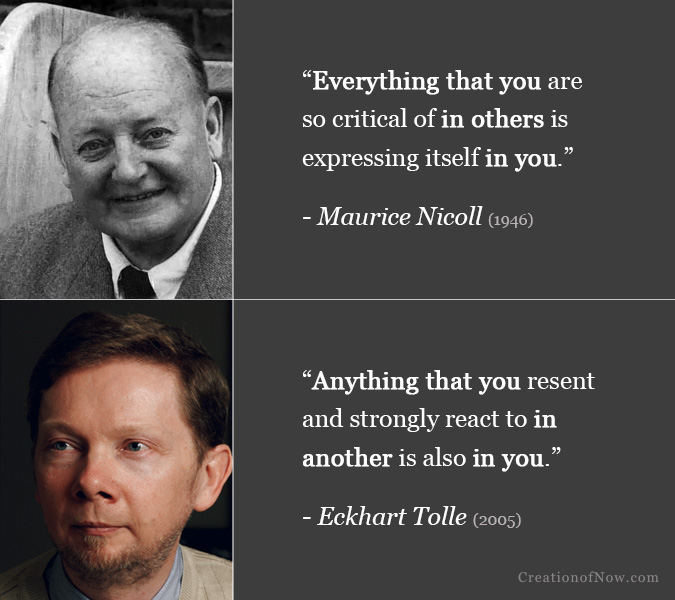

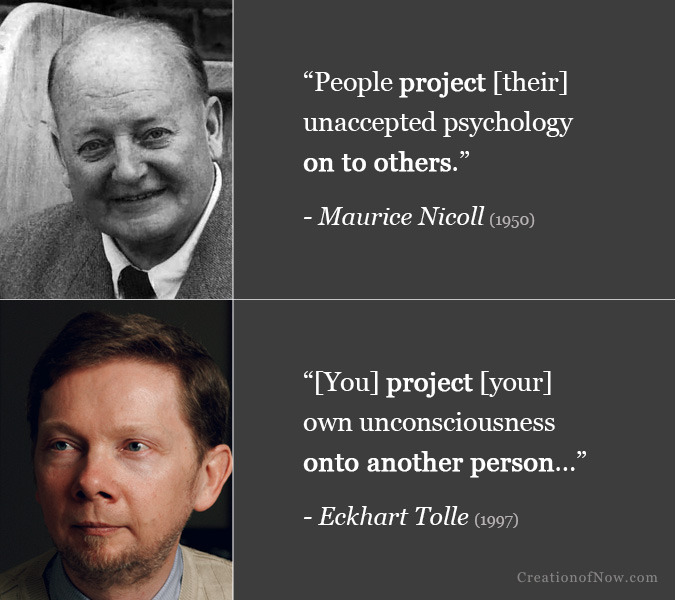

- We project our unconsciousness onto others. Any unconscious or “unobserved” aspects we are not yet conscious of tend to be projected onto others. The characteristics we most dislike, criticise or react to in other people typically exist in us but have not been observed, understood and accepted as existing in us yet. Nicoll drew upon Jung’s notion of shadow projection here,[28] but again proposes self-observation as the solution. Tolle continues this trend.

I’ll now compare their treatment of each main point of correspondence in greater detail.

Directing the light of consciousness within

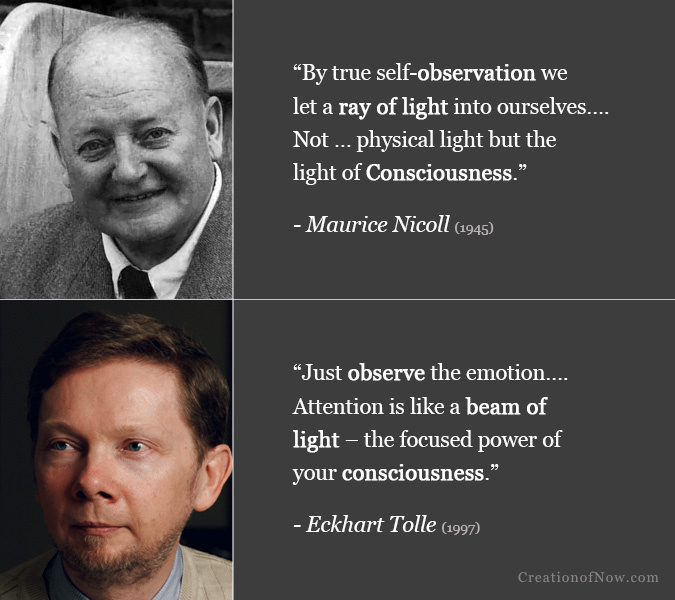

Both Nicoll and Tolle explain that “the light of consciousness” shines upon one’s unconscious processes, as they are occurring, by the act of inner observation. They use the phrase, “the light of consciousness,” or close variations, repeatedly when describing self-observation.

We bring the light or flame of consciousness into our inner darkness through self-observation.

A variation Nicoll uses is “the light of self-observation” and, in one instance, “the light of inner perception.” Tolle has more variations. He also refers to “the light of presence,” “the light of awareness,” and sometimes personalises the wording as “the light of your consciousness” or “your conscious presence”/“your presence.” More rarely, both characterise consciousness as an inner fire: Nicoll refers to “the fire of increasing Consciousness” and Tolle to “the flame of your consciousness.” The light of consciousness is brought into action within by self-observation and is therefore connected with one’s attention—as, in other cases, which I’ve highlighted before, they both explain that self-observation involves directing one’s attention inwards. They also equate consciousness with light in a more general sense without direct reference to self-observation.

Nicoll mentions “the light of consciousness” being cast inwards numerous times in his commentaries. He often refers to it as a “ray of light” revealing what is within us. Light is synonymous with attention in this context, as Nicoll tells us in various ways that self observation “is inner attention” and this ray of light. Gurdjieff is recorded using “ray of light” once in this context in the source material, but Nicoll amplifies this idea, employing the phrase more than 50 times. This “ray of light,” he makes clear, is “the light of consciousness”. He also uses “ray of consciousness” and, on one occasion, “beam of observation” with the same meaning—to describe the action of the light of consciousness cast inwards in self-observation which reveals unconscious processes happening within, including thoughts and feelings, which can be observed without identifying with them. He indicates the light of consciousness is “the remedy” for dealing with unconsciousness.[29]

There are many examples of Nicoll using these expressions in this context; here are just a few (select the down arrow underneath to expand the view and see more relevant passages).

Examples: Nicoll

“By true self-observation we let a ray of light into ourselves. Through this ray of light we may see a thing in us, but … of course a ray of light does not mean physical light but the light of Consciousness.”[30]

“Now what is this ray of light that is let into our inner darkness through practising self-observation? This ray of light is consciousness.”[31]

“‘So the Work says: Self-observation is necessary. It lets a ray of light into the inner darkness of ourselves.’ What is this ray of light? This ray of light means the light of consciousness, for consciousness is light … spiritual light, psychological light. And the inner darkness means all that side, all those qualities, that we are not conscious of, not aware of, and do not acknowledge.”[32]

“As said, a thing in you that you are unconscious of has great power over you like an invisible magnet. I repeat that the remedy is the light of consciousness. This Work is based on increasing the light of consciousness. It is about our becoming more conscious—we who live in darkness—by self-observation and long work on ourselves…. When [something in us is] dragged into consciousness—painfully, at the expense of your self-conceit—it loses its power. You gain the force it was eating. Only as long as it is hidden in unconsciousness has it power.”[33]

“Now in seeing this other side of ourselves, this dark side, into which the Work tells us that we must penetrate and make it increasingly conscious to ourselves by self-observation…. we have to see this dark side but not to identify with it. We have to make it conscious but not take it as ourselves.”[34]

The act of self-observation is said to cast a “ray” or “beam” of light into the psyche

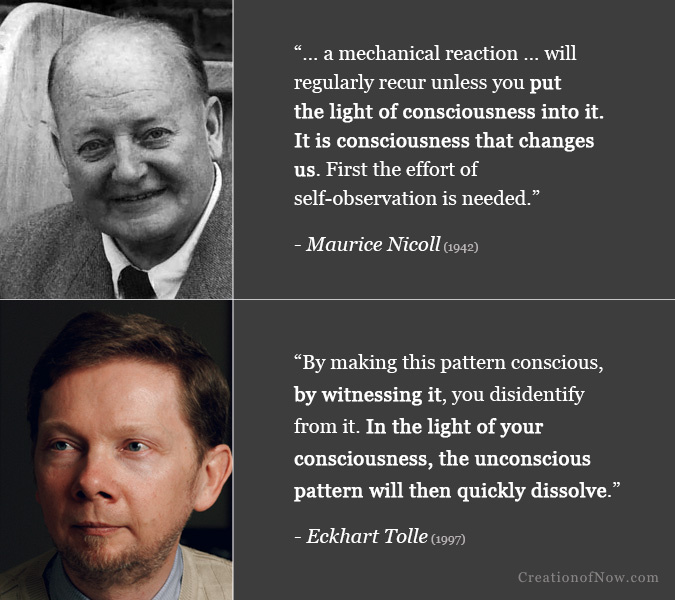

Tolle also uses the phrase “the light of consciousness,” or close variations, recurringly in connection with inward observation or conscious attention—also referred to as “witnessing”, “presence” or being “the watcher, the observing presence” etc. Similar to the “ray of light” or “beam of observation” references used by Nicoll, Tolle describes the inner attention present in observation as “a beam of light” or “spotlight” which is the “focused power of your consciousness” or “presence.” This allows you to observe or recognise unconscious attributes within and “disidentify from” them, including emotions and thought patterns. “The light of consciousness is all that is necessary” to deal with unconsciousness, he suggests.[37]

Examples: Tolle

“Watch out for any kind of defensiveness within yourself…. By making this pattern conscious, by witnessing it, you disidentify from it. In the light of your consciousness, the unconscious pattern will then quickly dissolve.”[38]

“Whatever it is, catch it before it can take over your thinking or behavior. This simply means putting the spotlight of your attention on it.”[39]

“Attention does not mean that you start thinking about [an emotion]. It means to just observe the emotion…. Attention is like a beam of light – the focused power of your consciousness.”[40]

“So … if you can catch it early on … the fear … or the anger, or whatever form the pain-body takes … you will be there as the awareness in the background while it happens. And … [then] the pain-body cannot control your thinking because you’re shining the light of consciousness on it.”[41]

“When you recognize the unconsciousness in you, that which makes the recognition possible is the arising consciousness, is awakening…. The light of consciousness is all that is necessary.”[42]

“Deep unconsciousness … usually needs to be transmuted through acceptance combined with the light of your presence — your sustained attention.”[43]

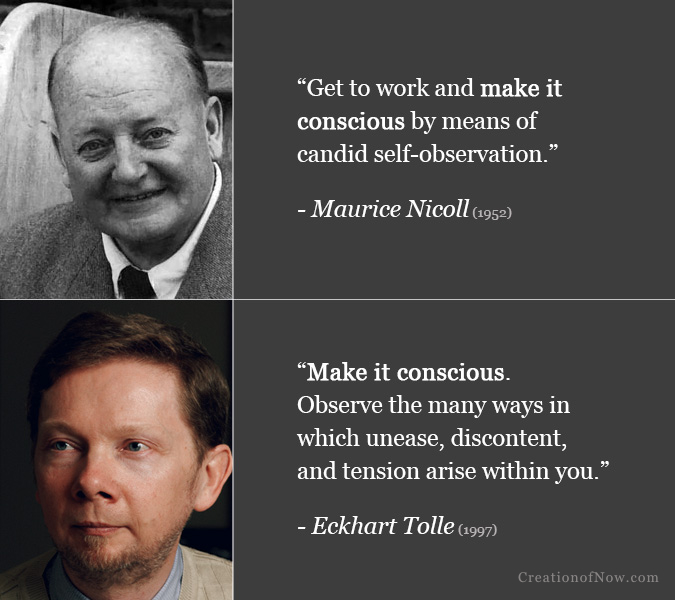

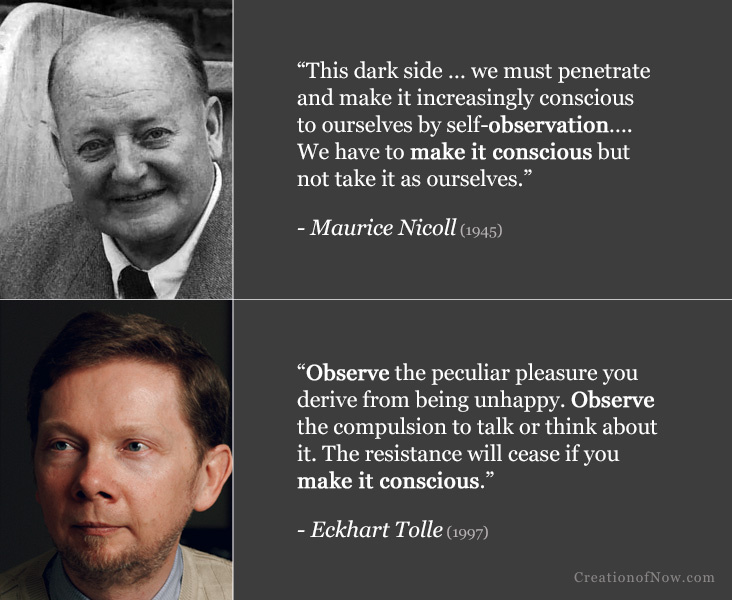

Bringing “unconsciousness” into the light to “make it conscious”

As already mentioned, both Nicoll and Tolle refer to the light of consciousness or presence as illuminating our “unconsciousness”. The idea of bringing dark unconscious factors into the light of consciousness through self-observation—or bringing the light of consciousness to it—is a recurring motif in their work. By doing this, we “make it conscious” they tell us—or use similar expressions to that effect. Only by becoming conscious or aware of what was previously “unobserved” or unacknowledged in us can we break free of its unconscious influence, they insist, and self-observation, by whatever name, is the method they advocate.

Both write of bringing what is unconscious into the light of consciousness through self-observation

In a lecture titled “The Unobserved Side of Ourselves,” written in 1946, Nicoll explains that people have an “unobserved” and “unknown or unconscious side” or “dark side” to their psychology that they have “not yet observed” or acknowledged. It must be made “more conscious to you” through self-observation for inner change to occur.[46] While this theme is a central focus of that lecture, he explores it many times throughout his commentaries and points to learning to see unobserved feelings and unobserved thoughts specifically.

Nicoll maintains that anything unconscious in our psychology that we are “not aware of” and “do not acknowledge” continues to operate unseen and, while it remains unknown and unacknowledged, can possess a person by its uncontrollable power. We must “make it conscious” [47] by bringing what is unconscious into the light of consciousness through self-observation to overcome it. He also describes consciousness as “an awareness” which shows you “what is going on in yourself”. Any unconscious factor has power over us while it remains hidden, but it loses power and one is gradually freed from its influence by the increase in consciousness that comes through practicing self-observation and facing it consciously.[48]

Examples: Nicoll

“The object of self-observation is to make us more conscious of what is in us. Unfortunately we move about in life imagining we know ourselves and not realizing we have another side that has to be made conscious gradually before we can begin to grow.”[49]

“All self-observation is to let light in—to oneself. Nothing can change in us unless it is brought into the light of self-observation—that is, into the light of consciousness—and all self-observation is to make us more conscious of what is going on in us.”[50]

“Make your dark, unobserved side more conscious to you … this dark—i.e. unconscious—side of yourself, the side that you do not know about yet, the side you have not yet observed.”[51]

“Self-observation is like a ray of light that penetrates the darkness inside us. The result of this ray of light is to bring into consciousness the unknown and unaccepted sides of ourselves.”[52]

“Whatever we bring into the light of consciousness loses the power it has over us if it remains unconscious—that is, in our inner, unexplored darkness.”[53]

“Get to work and make it conscious by means of candid self-observation. Why is it a good thing to make it conscious through candid self-observation?… [Whatever is] left in the shadows, in what is unconscious to you, in that region that you do not acknowledge and include in your inventory and conception of yourself … will be constantly at work in you all the same and, being possessed of the uncontrollable power that unconsciousness gives anything in you—that is, all you will not face—it may complicate your life to the point of tragedy.”[54]

The phrase “make it conscious” is used in connection with the self-observation process.

Tolle also writes of our “unobserved” psychology, referring at various points to the “unobserved mind”, “unobserved emotions” and “unobserved reactions” that run a person’s life when one is not present to observe them as the “witnessing consciousness, the watcher.” He likewise suggests that a person can break free of unconsciousness and its energy “by acknowledging it” which is only possible by observing it and facing it consciously by bringing it “into the light of consciousness”—which is your “observing presence.” Tolle also describes unconsciousness as “darkness”, equating “deep unconsciousness” with painful emotions and the “pain-body” which is “the dark shadow cast by the ego.” He writes of “bringing a light into this darkness” through conscious observation or attention—and describes this light as “the flame of your consciousness.” Like Nicoll, Tolle uses the phrase “make it conscious” in connection with this process and often points to the need to bring what is unconscious into the light of consciousness or “into the light of awareness,” or likewise “bring the light of your consciousness” into what you unconsciously identify with and fear. Only by doing so is unconsciousness diminished.[61]

Examples: Tolle

“[Question:] So how can we be free of this affliction [of ordinary unconsciousness]?

Make it conscious. Observe the many ways in which unease, discontent, and tension arise within you through unnecessary judgment, resistance to what is, and denial of the Now. Anything unconscious dissolves when you shine the light of consciousness on it.”[62]

“You no longer are the emotion; you are the watcher, the observing presence. If you practice this, all that is unconscious in you will be brought into the light of consciousness.”[63]

“The pain-body, which is the dark shadow cast by the ego, is actually afraid of the light of your consciousness. It is afraid of being found out. Its survival depends on your unconscious identification with it, as well as on your unconscious fear of facing the pain that lives in you. But if you don’t face it, if you don’t bring the light of your consciousness into the pain, you will be forced to relive it again and again. The pain-body … cannot prevail against the power of your presence.”[64]

“I had … witnessed a diminishment of the pain-body … through bringing the light of consciousness to it.”[65]

“Ego is the unobserved mind that runs your life when you are not present as the witnessing consciousness, the watcher.”[66]

“Observe the attachment to your views and opinions. Feel the mental-emotional energy behind your need to be right and make the other person wrong. That’s the energy of the egoic mind. You make it conscious by acknowledging it.”[67]

“Observe the resistance within yourself. Observe the attachment to your pain. Be very alert. Observe the peculiar pleasure you derive from being unhappy. Observe the compulsion to talk or think about it. The resistance will cease if you make it conscious.”[68]

One is to make what is unconscious conscious through self-observation

“Unobserved” thoughts cause a “build-up” of negative reactions

On a closely related point, both authors indicate our overall level of negativity and reactivity will worsen if our mind or thought is left unobserved. They suggest that we should closely observe our thoughts or mind to prevent a “build-up” of negative reactions.

Nicoll writes, “If your thought is unobserved, if you cannot see your thought, you will probably take every event negatively.” If one identifies with these thoughts then negative emotions will typically be roused in response. Even “the slightest negative reaction matters” and should be observed. Otherwise our “unobserved petty feelings” will “build up endless negative systems in us,”—“an accumulation of evil actions, thoughts and emotions”—that “mounts up” in oneself and becomes hard to deal with, he warns.[72]

Tolle similarly writes of the need to see one’s “unobserved mind” and the unobserved emotions arising in reaction to one’s compulsive thoughts. “Even the slightest irritation is significant and needs to be acknowledged and looked at; otherwise there will be a cumulative build-up of unobserved reactions.” If this process is unexamined it leads to an overall increase in negative reactions, emotions and thoughts, as “a vicious circle builds up” between your thinking and emotional reactions. [73]

Inner Transformation or Transmutation

In some examples we’ve looked at, the authors express the idea that the light of consciousness, directed within through self-observation (or witnessing, watching etc.) enables inner change by making unconsciousness conscious. This increases self-knowledge, but there is more to it than that. According to the authors, the light of consciousness itself has a transcendent, transformative power.

The light of consciousness is said to be the agent of inner change

Nicoll and Tolle portray the light of consciousness as an agent of inner change, producing transformative effects by its very presence. This is likened to a process of inner transmutation or transformation, which they associate with the “esoteric” meaning of ancient alchemical depictions of transmuting base metals into gold. They maintain that unconscious attributes can be disempowered or even dissolved in the illuminating gaze of conscious attention. They also suggest we have to fully acknowledge what is captured in its perception for change to occur.

I’ll now focus on these notions more specifically and compare how the authors present this process with respect to:

- The light of consciousness as the agent of change

- This change being the esoteric meaning of ancient alchemy

- Overcoming identification

- Disempowering and dissolving unconsciousness—including the “false self/ego” and accumulated negative emotional energy—in the “time-body” (Nicoll) or “pain-body” (Tolle)

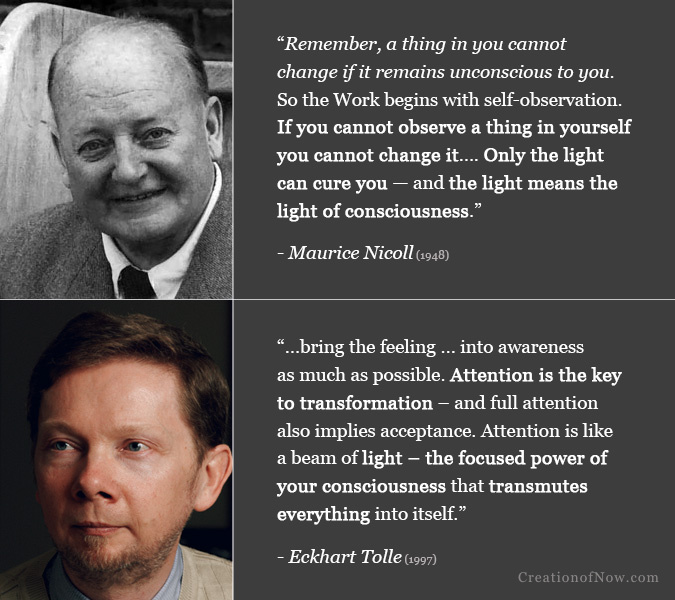

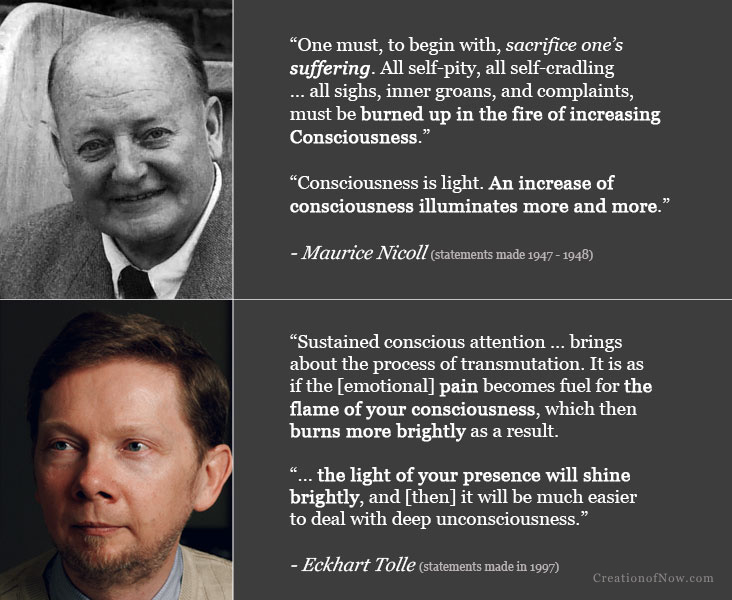

The light of consciousness as the agent of change

Nicoll maintains that “the light of consciousness” is brought into action through self-observation and gradually changes or transforms what it sees. “If you cannot observe a thing in yourself you cannot change it” he writes, and “it is the light of consciousness that begins to change things” and makes “inner transformation” possible. He points out that the “darkness of unconsciousness” within the psyche remains unchanged and active in the absence of this light, but when the light of consciousness is turned in upon oneself and falls upon an unconscious factor through self-observation, then “changes take place” through its “action” or “influence.” Nicoll also describes the need for negative states to be “burned up in the fire of increasing Consciousness.” “The light will cure us” is a line he often repeats in connection with this process, quoting what Gurdjieff once said to him.[74]

Nicoll also makes more generalised references to self-observation producing inner change or transformation without specific reference to light. There are far too many instances of that to discuss here (and my previous article explores the subject in depth). I’ll briefly note that Nicoll maintains that inner change comes about when self-observation is “continuous”, and that being aware of something within “is equivalent to a confession of it”. He also points out there must be “acceptance” or “acknowledgement” of what is seen without any self-justification to produce “self-change” and increase consciousness.[75]

Here are some examples of Nicoll discussing the light of consciousness, manifest through self-observation, as the agent of change:

Examples: Nicoll

“The object of self-observation, as it is said in the Work, is to let a ray of light into oneself…. When light is let in in this way many things begin to change of themselves. It is the light of consciousness that begins to change things. For this reason it is said in the Work that the light will cure us. Have you ever thought what it means, this extraordinary phrase: “the light will cure us”? When I first heard it said to me by [Gurdjieff] it had such an emotional effect upon me that I was unable to speak to anybody for some time afterwards.”[76]

“Remember, a thing in you cannot change if it remains unconscious to you. So the Work begins with self-observation. If you cannot observe a thing in yourself you cannot change it. Always remember this. Only the light can cure you—and the light means the light of consciousness.”1174

“We are living in a state of darkness, and nothing can be changed in us unless we let light into this darkness…. Self-Observation, by letting in light, begins to change us by its own action: for this light is consciousness.”[77]

“By letting light into inner darkness—that is, the light of consciousness—certain changes take place through its influence. Unpleasant things grow in the absence of light. It is the darkness of unconsciousness that is a danger. We have heard time and again that the Work is to increase our consciousness. ‘The darkness of ignorance and unconsciousness is to be dispelled by the light of consciousness.’”[78]

“A mechanical reaction … will regularly recur unless you put the light of consciousness into it. It is consciousness that changes us. First the effort of self-observation is needed.”[79]

“All self-pity, all self-cradling, vanity, secret, absurd fears, all self-sentimentality, all inner accounting, all pitiful pictures, all sighs, inner groans, and complaints, must be burned up in the fire of increasing Consciousness.”[80]

Tolle also suggests that the light of one’s conscious attention—“the focused power of your consciousness” or “presence” shining within—“brings about the process of transmutation” in a person. (As we’ve seen, “attention” directed inwards is synonymous with observation in Tolle’s work, as it is in Nicoll’s.)[88] Attention, Tolle says, “is the key to transformation.” Tolle variously describes this focused attention or consciousness directed within as a “spotlight,” “beam of light” or bright “flame” which “transmutes everything to itself,” including negative emotions.[89]

Comparable to how Nicoll advocates “continuous” observation, Tolle advocates “sustained” attention. Similar to how Nicoll speaks of the awareness of an inner state being equivalent to an inner “confession” of it, and that there must be “acceptance” and “acknowledgment” of what is seen, Tolle also writes of transmutation coming about through “acceptance” or “acknowledging” what is observed while keeping your conscious presence/attention on it. Tolle also describes observation producing inner change (transmutation) in a more general way, without references to light.[90]

Examples: Tolle

“Attention does not mean that you start thinking about it. It means to just observe the emotion, to feel it fully, and so to acknowledge and accept it as it is…. Some emotions are easily identified: anger, fear, grief, and so on. Others may be much harder to label…. In any case, what matters is … whether you can bring the feeling of it into awareness as much as possible. Attention is the key to transformation — and full attention also implies acceptance. Attention is like a beam of light — the focused power of your consciousness that transmutes everything into itself.“[91]

“Deep unconsciousness, such as the pain-body … usually needs to be transmuted through acceptance combined with the light of your presence — your sustained attention.”[92]

“Whatever it is, catch it before it can take over your thinking or behavior. This simply means putting the spotlight of your attention on it…. At the same time … be aware of your conscious presence and feel its power. Any emotion that you take your presence into will quickly subside and become transmuted.”[93]

“Observe the attachment to your pain…. You can then take your attention into the pain-body, stay present as the witness, and so initiate its transmutation.”[94]

“The pain-body needs your unconsciousness. It cannot tolerate the light of Presence.”[95]

“Sustained conscious attention severs the link between the pain-body and your thought processes and brings about the process of transmutation. It is as if the pain becomes fuel for the flame of your consciousness, which then burns more brightly as a result.”[96]

“To disidentify from the pain-body is to bring presence into the pain and thus transmute it.”[97]

“Through sustained attention and thus acceptance, there comes transmutation. The pain-body becomes transformed into radiant consciousness, just as a piece of wood, when placed in or near a fire, itself is transformed into fire.”[98]

“I had … witnessed a diminishment of the pain-body … through bringing the light of consciousness to it.“[99]

Esoteric Alchemy

Nicoll conveys the Fourth Way notion that alchemy really represents an “inner transformation”[101] and, as we have seen, links this process to self-observation specifically by presenting the light of consciousness, directed through self-observation, as the agent of this change. As mentioned in the introduction, Gurdjieff associated this process of inner change with alchemy in his early teaching:

“The idea of this [inner] transmutation was known to many ancient teachings as well as to some comparatively recent ones, such as the alchemy of the Middle Ages. But the alchemists spoke of this transmutation in the allegorical forms of the transformation of base metals into precious ones.”[102]

“The whole of alchemy is nothing but an allegorical description of the human factory and its work of transforming base metals (coarse substances) into precious ones (fine substances).”[103]

When Nicoll conveys this idea, he specifically refers to “esoteric alchemy” and distinguishes this “real alchemy” from other external forms that literally sought to turn lead into gold. He uses the words “ancient” and “esoteric” to describe this “real Alchemy, which is about “Man and his inner transformation,” that is, how “Man as base metal could be transformed into gold”—as distinct from “exoteric alchemy [which] was based on the idea that actual lead could be turned into gold.” In “ancient alchemical language” the purpose of the inner work “is to transmute ‘lead’ into ‘gold’” in the sense that “mechanical Man, symbolized by lead” is transformed “into Conscious Man, symbolized by gold.”[104]

Tolle likewise refers to alchemy representing inner change in its esoteric meaning. As we’ve seen, he writes that “sustained conscious attention … brings about the process of transmutation” and states that this is “the esoteric meaning of the ancient art of alchemy: The transmutation of base metal into gold, of suffering into consciousness”. In doing so, he uses similar descriptive words to Nicoll in connection with this meaning of alchemy, such as “esoteric”, “ancient” and a similar interpretation of the meaning of the “alchemical transmutation of the base metal of pain and suffering into gold.” In Tolle’s case, he is more specific that it is the pain-body or ego that is transmuted when he makes this point.[105]

An image from Liber Mutus, a 17th century hermetic alchemical text which Nicoll briefly mentions.

Note that in the Fourth Way, the kind of transformation referred to here is more multifaceted, as is typical of earlier forms of western esotericism. There is not just the aim of eradicating negative attributes within—although this is included—but also using and refining the energy gained from the process to create new subtle bodies by which higher aspects of the psyche can express and which continue beyond this life.[106] This kind of alchemical process of inner creation and refinement of new bodies, a process which goes beyond just the eradication of negative attributes, is not described in Tolle’s work.[107]

The power to overcome identification

In my previous article, I showed how Nicoll and Tolle present self-observation as the primary way to overcome identification. I summarised the concept of psychological identification as, “wrongly transferring our feeling or sense of “I” or “self” into inner states, thoughts, emotions and opinions or mental positions—which are not really us. Our identity then merges with these to such an extent that, for that moment at least, we ‘become’ our state or it ‘becomes’ us. And this is typical for most people much of the time.” This is a central premise of the Fourth Way teaching that Tolle mirrors.

Both Nicoll and Tolle advocate self-observation as the means to overcome this continual process of identification. The idea is that by consciously observing what is happening within, one can recognise inner states as transient phenomena distinct from one’s observing consciousness, and, from this vantage point of awareness, choose to cease going along with factors which otherwise would have compelled one unconsciously. As I summarised before:

“Self-observation is employed to see the mechanics of identification in action, giving one the option to “separate internally” from states one would otherwise identify with automatically when inner awareness is absent.”[108]

Overcoming identification with an inner state through self-observation, even momentarily, is called “non-identifying” or “disidentifying” by Nicoll and Tolle respectively. One of the effects of this is that whatever inner state, emotion or chain of thought is observed, and no longer identified with, begins to lose power over us, we are told. By repeatedly practicing this, a person can break out of their habitual or compulsive mental and emotional states, reactions and behaviours.

“It is the perceptual “light of consciousness” that breaks the spell of identification in the moment.”

I don’t wish to re-tread this subject in depth, only raise a closely related point I did not pinpoint before: the light of consciousness is the power that makes disidentification possible. Consciousness, according to both authors, is distinct from any psychic content. It isn’t memory, intellection, or any inner state, emotion or thought, but that quality of pure perception that sees things as they are—including inner states when they are directly observed operating within us. So by feeling our sense of self in consciousness, instead of transient psychic content, we are placed in something deeper that’s beyond any momentary phenomena observed. And it’s the active illuminating perception of this consciousness—directed inwards by self-observation—that reveals the real nature of the inner factors within us we are typically absorbed in unconsciously. One of the important truths it shows us is that our inner states are not who we are—and we see this simply by our capacity to observe them independently. It is the perceptual “light of consciousness” that breaks the spell of identification in the moment.[109]

Brought under the light of consciousness, Nicoll explains, the unconscious factors we observe in us become “not I” —or in other words, they are no longer identified with.

But aside from dispelling identification, and giving one a sense of freedom from habitual inner states, even briefly, the light of consciousness is said to have the capacity to disempower and even dissolve what it observes and illuminates, according to the authors. We’ve already touched upon this in some previous examples, but I’ll now highlight some instances where Nicoll and Tolle describe this idea more specifically.

Disempowering or dissolving “unconsciousness”

Nicoll states that when we bring something unconscious into the light of consciousness through self-observation it “loses the power it has over us”, “loses its power” or is robbed or “deprived of its power.” Something unconscious has “great power over you like an invisible magnet” if it remains “hidden in unconsciousness” he writes, and “the more unconscious a thing, the more power it exerts on us.” But through self-observation, the “ray of light … of consciousness” enters “into the darkness, the ignorance of oneself” and “very slowly brings about a change.” By this process, “the darkness of ignorance and unconsciousness is to be dispelled by the light of consciousness.” He often emphasises this inner change is gradual, however, explaining that by observing something recurringly we are “gradually freed, gradually made less and less under its power” and that “for this, long self-observation is needed and much patience with oneself.” As this process continues any factor observed is said to become “less dominating” as consciousness increases.[110]

Unconsciousness is said to lose power under the light of consciousnesses

Tolle similarly writes that a thought, “loses its power over you” when your “conscious presence” is aware of and “witnessing the thought.” He also points out “inner factors” such as fear and guilt, “will dissolve in the light of your conscious presence”. “It is a silent but intense presence that dissolves the unconscious patterns of the mind,” he explains. “They may still remain active for a while, but they won’t run your life anymore.” In contrast to Nicoll, Tolle does not emphasise that the process of overcoming unconsciousness is gradual and difficult; in fact he at times suggests the opposite: “If you were conscious, that is to say totally present in the Now, all negativity would dissolve almost instantly.” “In the light of your consciousness,” an “unconscious pattern will … quickly dissolve.” “By focusing all your attention on the Now, the unconscious resistance is made conscious, and that is the end of it.”[111]

Dissolving the false self or ego

I have discussed the concept of the egoic false self in previous articles; this illusory sense or feeling of identity is one of the primary unconscious attributes the authors write about overcoming through self-observation. Both authors suggest the false self—the false personality or ego—can be dissolved in the light of consciousness through self-observation.

Nicoll describes the light of consciousness gradually dissolving our “False Personality” as it “destroys [our] illusions about ourselves.” [112]

Tolle similarly suggests that unconscious patterns of your “illusory identity” which is the “fictitious” ego will “dissolve” in “the light of your consciousness” when you witness it. However, when you are not present to observe the ego then it “runs your life”—but it is ultimately an “illusory self” with a “phantom nature” and “if you can recognize illusion as illusion, it dissolves.” When you observe the ego as “the witnessing presence” it will “lose its grip on you” as you “grow in presence power”. “Anything unconscious dissolves when you shine the light of consciousness on it” through observation, he explains. As you continue in this way “the light of your presence will shine brightly”, he claims, and then you can “deal with deep unconsciousness whenever you feel its gravitational pull”.[114]

Once again, a big point of difference is that Nicoll is very clear that dissolving the false or imaginary “I” is a gradual process of inner work, whereas Tolle insists the complete collapse of the egoic false self can be a near instant event in “rare cases”[115] with “rare beings”[116]—and suggests this was the case for him.[117]

Negativity within

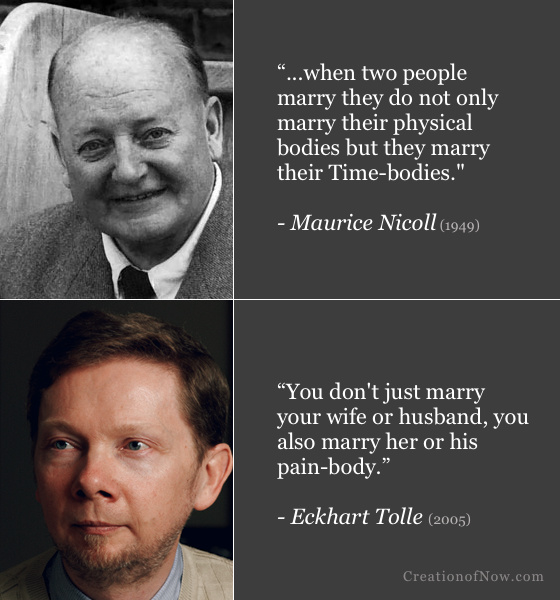

Both Nicoll and Tolle posit the existence of psychic bodies that store an accumulation of negative emotional energy, constituting the “living past” in us. This is the “time-body” and “pain-body” respectively.

Interestingly, Nicoll and Tolle inform us that we also marry our partner’s time-body or pain-body, not just their physical body, and advise us it would be best to have a partner whose time/pain body is not too “negative” or “dense” respectively. “A negative time-body,” Nicoll tells us, “is a bad kind of time-body to have.”[118]

We’re said to marry our partner’s time-body or pain-body as well

The idea of dissolving or destroying unconsciousness with the light of consciousness extends to the accumulation of negative emotional energy stored in these particular psychic bodies, and the method is much the same.

There is a “mass of useless suffering stored up in our Time-Body” Nicoll tells us. One can “transform the Time-body, if it is negative” by living “more consciously now” and “observing when you take situations in life negatively” and ceasing to identify with your typical reactions. This allows the light or force of consciousness to be “shed … into the time-body” and transform it. The light of consciousness, according to Nicoll, “is the force that changes us” and “alters the past” which is “living in us” as well as the future. [119]

“Now this light of consciousness is shed also into the past, into the time-body…. Remember that every stage of slightly increased consciousness begins to alter us and the past. The past is living in us…. Whatever you do now alters the past, as well as the future…. Consciousness is the force that changes us.”[120]

“Now to transform the Time-body, if it is negative, you must work on yourself now and stop now this facile mechanical way of taking everything that happens to you…. That is to say, by working on yourself more consciously now through observing when you take situations in life negatively, you can alter not only the future but the past.”[121]

Self-observation is also the means to deal with the negative part of the emotional centre. This is described as an unnatural psychic growth or infection disrupting our normal emotional capacities that exists solely to generate and feed on negative emotions.

Nicoll suggests various negative emotions can be killed or burned up as they are brought into the light or fire of consciousness through self-observation:

“What kinds of jealousy can we observe and slowly drag, as it were, struggling like snakes, into the light of consciousness which kills them?”[122]

“All self-pity, all self-cradling, vanity, secret, absurd fears, all self-sentimentality, all inner accounting, all pitiful pictures, all sighs, inner groans, and complaints, must be burned up in the fire of increasing Consciousness.”[123]

However to be “purified from negative emotions” more completely the negative emotional itself part must be continually “starved” of the energy it feeds on and “lessened in its power” by continuous self-observation and non-identification with the various negative emotions it produces. It can eventually be “destroyed in us” by this method as we “begin to dissolve our ordinary mechanical feeling of ourselves.” [124]

Bringing negative states into the light of consciousness by observation/attention is said to change or transform them.

In Tolle’s work many of these facets converge into a single concept: the pain-body. This both stores emotional pain or negativity, like the time body, and expresses it, like the negative part of the emotional centre. The pain-body, “is the living past in you, and if you identify with it, you identify with the past,” Tolle writes, and “if you don’t bring the light of your consciousness into the pain, you will be forced to relive it again and again.”[125]

Tolle similarly directs the reader to observe or witness the pain-body—which can be seen as “a heavy influx of negative emotion when it becomes active”—in order to stop identifying with its negativity and thereby “transmute” it with your conscious presence. One should “focus attention on the feeling inside” by “putting the spotlight of your attention on it.” “For love to flourish, the light of your presence needs to be strong enough so that you no longer get taken over by … the pain-body,” he writes, but this can only happen permanently when “your presence is intense enough to have dissolved the pain-body” entirely. However, in most cases it “does not dissolve immediately” but gradually loses energy as it is “transmuted into presence”.[126]

Similar to Nicoll’s advice to live “more consciously now” and observe your negative reactions to transform the time-body and eliminate negative emotions and thereby “alter … the past” living in us, Tolle views being conscious in the present and watching your typical reactions as the means to deal with the “unconscious past” in you.

“There is no need to investigate the unconscious past in you except as it manifests at this moment…. Access the power of Now. That is the key.”[127]

“Give attention to the present; give attention to your behavior, to your reactions, moods, thoughts, emotions, fears, and desires as they occur in the present. There’s the past in you. If you can be present enough to watch all those things … then you are dealing with the past and dissolving it through the power of your presence.”[128]

As a side note, I should briefly mention that present-moment observation, while certainly primary in Nicoll’s work, is not advocated as exclusively as it is in Tolle’s. While Tolle suggests, in the examples above, that there is no need to look back at the past, Nicoll does mention the benefits of retrospective analysis from time-to-time and hints at a “retrospective observation” practice one can do. It would indeed be strange if he saw no value in this, given his background as a psychiatrist. [129]

The light of consciousness grows stronger

We’ve already seen the authors describe how unconscious factors lose power when brought into the light of consciousness by self-observation. As an extension of this, they convey the closely related idea that the power an unconscious factor loses is in some way gained by consciousness. They also suggest the light of consciousness or presence becomes brighter and stronger, increasing or growing in its power or illumination, as it overcomes unconsciousness through self-observation.

The fire, flame or light of consciousness is said to grow brighter as it burns up psychological pain and suffering.

“This Work is based on increasing the light of consciousness,” Nicoll tells us, and, “self-observation gradually increases light.” The light of consciousness increases as the “living darkness in ourselves” is “cleared away” by the “increasing light of consciousness through self-observation.” This “increasing light” comes from observing “a part of the darkness” and “bringing it into consciousness,” and this includes all of our unconscious actions, words, thoughts, emotions, feelings and what we “say and do”. The “inner darkness” and negativity then reduces and becomes “less dominating” as it is “burned up in the fire of increasing consciousness” and “you gain the force it was eating”. There is therefore a “growth of consciousness” as “the light of self-observation is thrown into this dark side” of ourselves, Nicoll suggests. As the light of consciousness increases it broadens and “illuminates more and more.” [130]

In a similar vein, Tolle states that “the light of your presence will shine brightly” when you “observe” and “shine the light of consciousness” on “ordinary unconsciousness” and thereby begin to dissolve it. He writes that “the light of your consciousness grows stronger” every time you disidentify from your mind through being present to observe it. One should aim to reach a point where “the light of your presence” is “strong enough” so that you are no longer “taken over” by egoic thinking or the pain-body. The ego loses its grip upon you by observing it as the “witnessing Presence,” and as this happens you “grow in presence power”. The same is true of the pain-body which “consists of trapped life-energy that has split-off from your total energy field”. By placing “sustained conscious attention” upon it “the pain-body begins to lose energy.” The energy it loses is simultaneously “transmuted” and “becomes fuel for the flame of your consciousness, which then burns more brightly as a result.” [131]

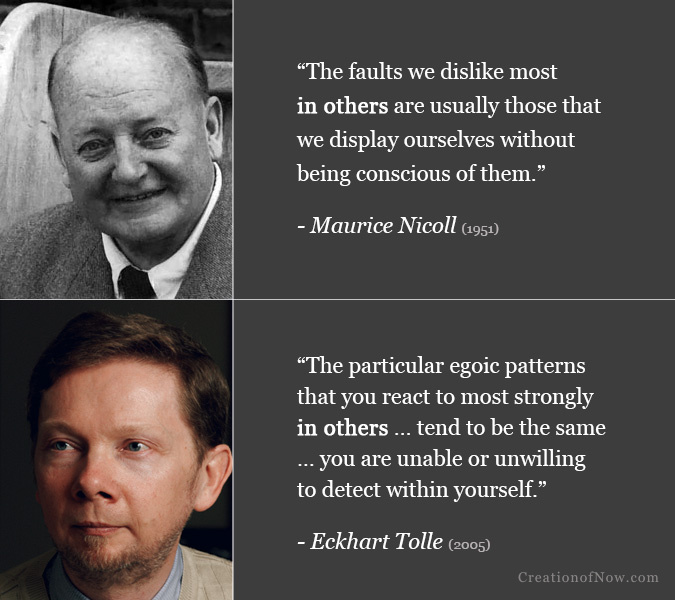

Projecting unseen unconsciousness onto others

We now turn to a psychological effect the unconsciousness in us, which the light of consciousness is yet to reveal, can have on our outlook and behaviour, which both authors describe in similar ways.

Nicoll and Tolle both suggest that the attributes we most dislike, criticise or react to in others typically exist unobserved in us. We only see these unconscious faults externally in others, and tend to be overly critical, judgemental or annoyed by attributes they display that remain hidden in us. In some cases, people can entirely project their unknown faults onto others, even when it’s absent in the other.

The faults we dislike most in others may exist unrecognised in us

Both suggest we try to see the characteristics we find most objectionable or offensive in other people within ourselves—claiming there is nothing we can condemn or strongly react to in others that is not in us as well. If we could see and understand this, they maintain, we would naturally become less judgmental or resentful, and could interact with others without reacting emotionally to their unconscious behaviour or taking it so personally.

This is essentially a variation of Jung’s idea of “shadow projection”—the notion that people unconsciously “project” their unrecognised undesirable attributes, which lie hidden or buried in their psychological “shadow,” onto other people, to avoid seeing and confronting it in themselves.[132] In his commentaries Nicoll makes frequent reference to the “dark side of ourselves” that we “see only in other people and do not attribute to ourselves”[133] and directly references Jung’s notion of shadow projection in connection with this.[134] However, unlike Jung’s analytical psychology, the self-knowledge methodology of the Fourth Way—self-observation—is put forward as the means to see and overcome this.

“Gurdjieff held that since it is human nature to see the faults of others more easily than our own, we should use other people as “mirrors” in which to see ourselves…”

Nicoll combines Jung’s idea of shadow projection—itself a variation of the wider idea of psychological projection—with similar notions of Gurdjieff’s. Gurdjieff held that since it is human nature to see the faults of others more easily than our own, we should use other people as “mirrors” in which to see ourselves when pursuing self-study through self-observation. We will thus begin to see our unknown faults displayed by others first before we start to notice them in ourselves. But Gurdjieff stressed that learning this way is only possible if we accept that the faults of others are also in us: “in order to see himself in other people’s faults and not merely to see the faults of others, a man must be very much on his guard against and be very sincere with himself.”

These ideas converge in Nicoll’s commentaries, becoming greatly emphasised and linked closely with “the light of consciousness.” “The increasing light of consciousness through self-observation” is the means to “become more conscious of this dark side of ourselves” that we typically “only see … reflected into other people,” he tells us. In becoming conscious of this side of ourselves we gain “the capacity to bear the unpleasant manifestations of others. One does not continually get negative with other people.” [135]

“In his writing, Tolle presents these notions with a similar meaning and context to Nicoll…”

In his writing, Tolle presents these notions with a similar meaning and context to Nicoll, although not nearly as often, and without direct reference to the “shadow” or “dark side” of the psyche specifically. Yet he does allude to this indirectly by describing “the pain-body” as “the dark shadow cast by the ego” which is “afraid of the light of your consciousness.” The pain-body carries and accumulates our un-faced emotional pain within, which gets projected outwardly “into events and situations” in ways that “reflects back its own energy,” he tells us, and “it’s more important to observe it … in yourself than in someone else.”[136]

I’ll now look more closely at how they present the idea of recognising the faults we see in others in ourselves through self-observation, and the benefits deriving from this.

The faults we despise most in others exist unseen in us

Both authors tell us that whatever traits we most react to, criticise or dislike in others tend to exist un-faced within us.

Nicoll writes that “the faults we dislike most in others are usually those that we display ourselves without being conscious of them.” “What we are unconscious of in ourselves we tend to see only in others,” he explains. This tendency is tied to the notion of projecting the dark side of one’s psychology onto others: “The thing you criticize so much in other people is something lying in the dark side of yourself that you do not know or acknowledge” and “we project this side of ourselves and see it in other people.” Therefore we need to “realise that there is nothing that you can condemn in another person that is not in yourself as well” and “everything that you are so critical of in others is expressing itself in you.”[137]

Tolle similarly writes that “the particular egoic patterns that you react to most strongly in others … tend to be the same patterns that are also in you, but that you are unable or unwilling to detect within yourself”. He further claims that “anything that you resent and strongly react to in another is also in you.”[138]

Observing an antagonist’s negative qualities in ourselves

The authors suggest that we use occasions where a person opposes us or causes difficulties to observe any negative characteristics they exhibit within ourselves. Both indicate self-observation is the means to do this.

Nicoll and Tolle word this idea in quite similar ways

Nicoll suggests that, “as a general rule” whenever “we are up against someone else” or “cannot stand” them they may be characterising “the very thing we have to work on in ourselves.” When this happens, we “see them as liars, or unfaithful, or mean, or untrustworthy, and so on, in relation to our own qualities.” Thus you should “really observe yourself” in such cases and “try to find in yourself what … you are critical and violent about in the other person.” “Do not think what you see in others cannot possibly be in you.” He reiterates the idea that others “are mirrors of yourself” who can show you “what you need to see in yourself and become conscious of” provided you genuinely seek to “find in yourself what you judge so critically in others.”[139]

Tolle also writes that you have “much to learn from your enemies” and should look at whatever it is in them “that you find most upsetting, most disturbing” whether it is “their selfishness” or “insincerity, dishonesty, propensity to violence, or whatever it may be.” You should understand that the same things are “also in you” and that “observing” them “within you” is beneficial. He also expresses the notion that what you see and react to in others can be a “reflection” of what’s in yourself and a means to become aware of it. “Very unconscious people experience their own ego through its reflection in others,” he writes. “When you realize that what you react to in others is also in you (and sometimes only in you), you begin to become aware of your own ego.”[140]

Understanding, and not reacting to, the unconsciousness of others

When we do come to recognise the characteristics we resent or dislike in others within ourselves, the authors tell us, we become less judgmental and reactive towards people and gain more understanding for their shortcomings, such as their unconscious behaviour or manifestations.

“People project [their] unaccepted psychology on to others,” Nicoll writes, but when your own faults become “conscious to you” they are “no longer projected” on others. Then your relationships improve—you no longer condemn, react, judge or fail to forgive so easily. By observing in yourself what you dislike in others, you gain more understanding for another’s “inner difficulties” through realising the other person “has also this thing that you have noticed in yourself.” In this way we become better able to “endure one another’s unpleasant manifestations” without having “personal reactions” in response and “continually being upset and hurt,” or “over-critical.” “You are no longer surprised and indignant with others, which is a tedious and exhausting role to play.” Instead one can put oneself “in the other person’s position” with genuine sympathy and “see them in yourself and yourself in them” and feel “with the other person”—but only when you “see through yourself” and observe your “own unpleasant manifestations” first of all so that “your own feelings are conscious to you.”[141]

The idea of psychological projection converges with self-observation in Nicoll’s work. Tolle continues in this vein.

Tolle also writes of how people “project [their] own unconsciousness onto another person and mistake that for who they are.” In this state, he explains, “instead of overlooking unconsciousness in others, you make it into their identity. Who is doing that? The unconsciousness in you, the ego. Sometimes the ‘fault’ that you perceive in another isn’t even there. It is a total misinterpretation, a projection…. At other times, the fault may be there, but by focusing on it, sometimes to the exclusion of everything else, you amplify it. And what you react to in another, you strengthen in yourself.” But your interactions with others improve and become more “impersonal” when you no longer take their unconsciousness or reactions for who they are—in the same way that you learn to no longer take the unconsciousness observed in yourself for who you are.[142]

Closing Comments

As we have seen, there are many ways Eckhart Tolle’s discussion of the light of consciousness, directed inwards through self-observation, corresponds with Maurice Nicoll’s earlier formative treatment of this subject.

Nicoll’s work on this theme was distinctive and innovative in the way he seamlessly fused the Jungian focus on bringing the unconscious dark side of our psyche into the light of consciousness as the basis for self-development, with Gurdjieff’s emphasis on the present-moment practice of self-observation as the primary method to actualise this process.

” … the obvious parallels between the primary practical exercise Tolle teaches and the practice of self-observation found in the Fourth Way, particularly as presented by Nicoll, are there for all to see.”

Having been a student of Gurdjieff, Ouspensky and Jung, Nicoll was in an extremely unique position. He brought all the self-knowledge principles he had learned together and, combining it with his own insights, described self-observation in a rich, practical and dynamic way. He was also teaching at an important historical juncture; the 1940s and early 50s, well before the rise of the mind-body-spirit scene and the popularisation of similar practices like mindfulness in the West. In many ways, the evocative language and themes he used set the tone for much of what came after. I believe his work remains influential in this space to this day; the many correspondences his writing shares with Eckhart Tolle’s certainly suggests this.

However, while Nicoll often speaks of the difficulty of this inner work, Tolle, in contrast, does not emphasise that a prolonged struggle or confrontation with the darkness of unconsciousness is necessary—as Nicoll, and the sources he drew on, often do. While Tolle does share an emphasis on bringing unconscious factors, including the “pain-body”—the “dark shadow” of the ego—into the light of consciousness via present-moment observation to transform it, he also dismisses the need for any prolonged inner “work” or struggle and downplays any hardship involved in the process. We do not “need to work hard for or struggle to attain” inner joy and peace, he tells us, as it is our “natural state.” “As soon as you honor the present moment,” he writes at one point, “all unhappiness and struggle dissolve, and life begins to flow with joy and ease.” [143]

As I’ve noted before, Tolle has other influences more aligned to these sentiments. This line of thinking has been dubbed “immediatism” by the religious scholar Arthur Versluis[144] and I have discussed its presence in Tolle’s work, and the contradictions arising from its apparent admixture, in a previous article. I noted:

In my personal opinion, Tolle’s hesitancy to acknowledge more plainly that the process of confronting unconsciousness within is not quick and easy—and certainly not a continual process of joy and ease—will undoubtedly cause confusion or disappointment for some. His explanations leave someone ill-prepared for the difficulties inevitably faced when sincere self-observation is carried out. These are glossed over too much.[145]

In spite of these differences and discrepancies, the obvious parallels between the primary practical exercise Tolle teaches and the practice of self-observation found in the Fourth Way, particularly as presented by Nicoll, are there for all to see. This is the second in-depth article I have written highlighting the correspondences between Tolle and Nicoll on this practice specifically (see the introduction and part 1 for more on this).