Taking responsibility for one’s inner state, whatever life’s external conditions, is a recurring idea in the work of Maurice Nicoll and Eckhart Tolle. Self-observation brings a shift in perspective that makes this possible, they suggest; we can gain “inner freedom” and overcome negative tendencies by consciously seeing and transforming inner reactions to life’s events as they happen. This article continues my investigation into how Nicoll and Tolle describe the present-moment practice of self-observation in similar ways. In this third part, I explore how they correspond on the theme of shifting one’s inner approach to life.

Practicing self-observation, we are told, involves a major perspective shift. One not only learns to look within during life’s moments, but turns their whole outlook around to make their inner world primary.

Far from making one self-absorbed, however, this is supposed to allow us to engage with the world and other people with more consciousness, attention and energy. The idea is that by transforming how you take life’s events psychologically in real-time, our responses, actions, behaviour and choices can be transformed for the better too. It’s a method for what Maurice Nicoll sometimes called “living consciously”—decades before that kind of language became more common and somewhat overused.

This inner shift in one’s approach to life is what this third article in my series on self-observation is concerned with. I’ll explain further what this entails first of all, as it can be difficult to fully grasp the idea without some prior familiarity.

Then I’ll look at similar ways Nicoll, an early 20th century teacher in the Fourth Way tradition, and Eckhart Tolle, a bestselling contemporary spiritual author, discuss this shift and its benefits—such as the inner freedom, peace and greater self-responsibility it’s said to bring. As we’ll see, they have much in common to say about this too.

New readers here may want to check out my introduction to this series and its previous two instalments first. To briefly recap, I’ve been exploring the many similar ways Nicoll, a relatively obscure author who died in 1953, and Tolle, a present-day celebrity of New Age spirituality, describe the practice of self-observation. Part one surveyed their tips and advice on how to bring this practice into daily life, while part two showed how they both describe the light of consciousness producing inner transformation by means of it.

I’ve endeavoured to make the following analysis self-explanatory however. So, if what I’ve written so far hasn’t lost you, starting here should not be an issue.

You can opt to expand and read the prologue below if you wish, which provides some philosophical background to the theme examined here. Otherwise, just continue straight on to the “summary of correspondences” section for in-depth comparisons of Nicoll and Tolle on this subject.

A conscious shift in perspective on life

Summary of correspondences

Both Nicoll and Tolle discuss the theme of consciously shifting our perspective on life—and our psychological reactions to life—in a multitude of corresponding ways. Very broadly speaking, their commonalities around this theme can be summarised in the following five points:

- Prioritising the inner reality. Both stress the importance of observing our inner reality of inner states, which we should consider to be as or more important as the external world or reality. Our inner states can attract certain outer life situations, they say, and to change our states we must distinguish our psychological reactions to life’s events from the situations themselves. Both use the example of observing how we react to bad weather to illustrate this idea, and cite the same Gospel passage to stress the importance of changing how we respond to other people’s faults, in order to focus on addressing our own reactions.

- Inner freedom, peace and choice. By becoming conscious of our habitual reactions to life, we gain a new “power of choice,” within the moment, over how we respond internally and externally, they tell us, and can find a sense of “inner freedom” and “inner peace” that’s independent of external conditions. Both cite the same biblical passage to describe such peace.

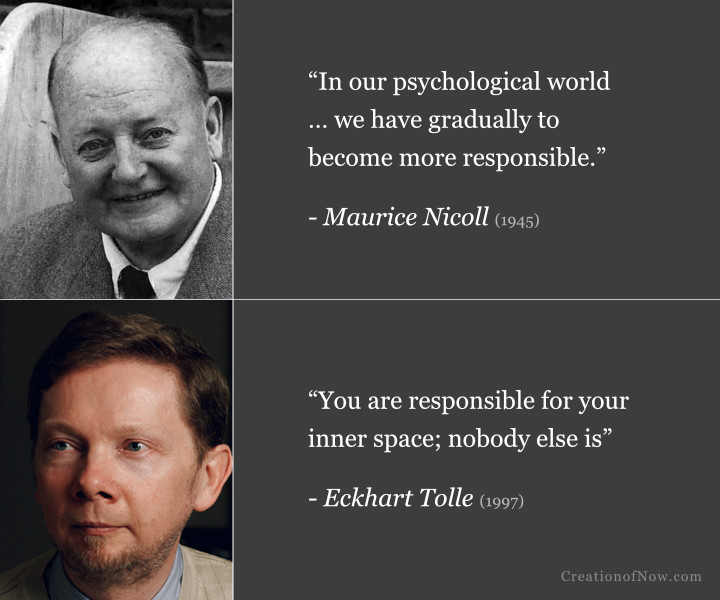

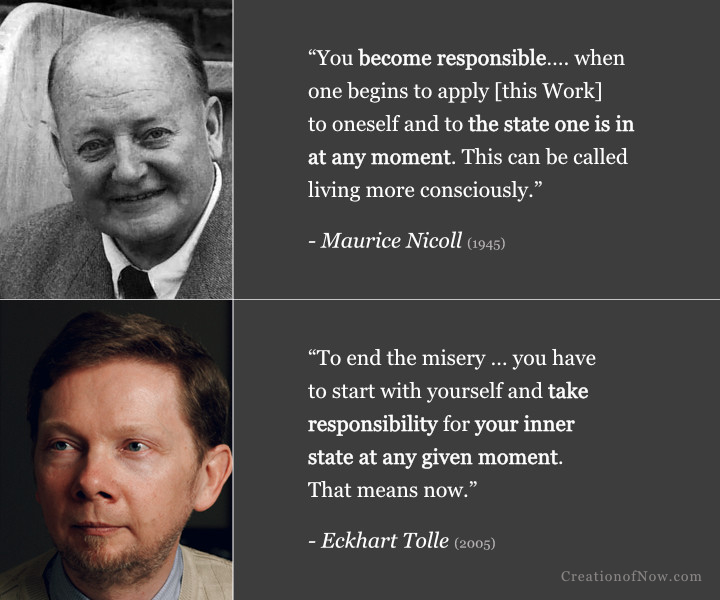

- Personal responsibility for inner states. Becoming more conscious of one’s inner world through self-observation, and changing it, entails taking responsibility for one’s inner state irrespective of circumstances. Both stress this must occur at any given moment. Only if individuals take charge of their own psychological world or inner space in this way can they address their own unhappiness, which affects not just themselves but the world, and so this is where any real change must begin. Those who become more conscious are said to acquire greater inner responsibility in this respect.

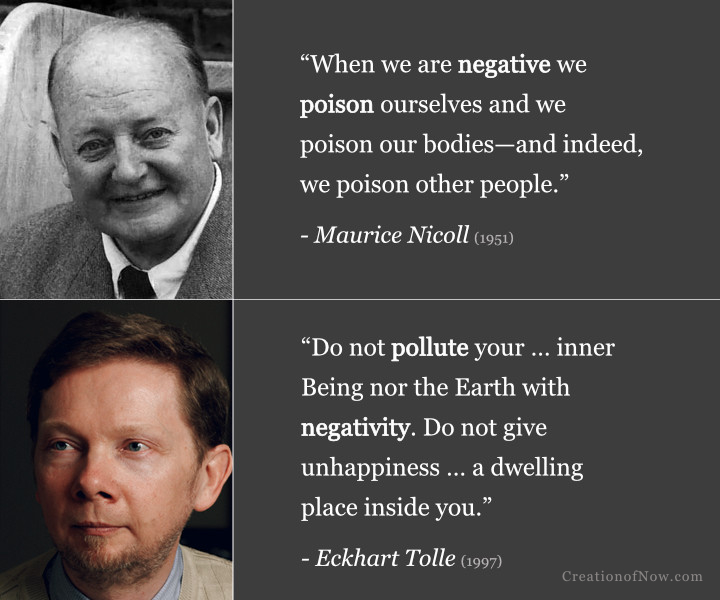

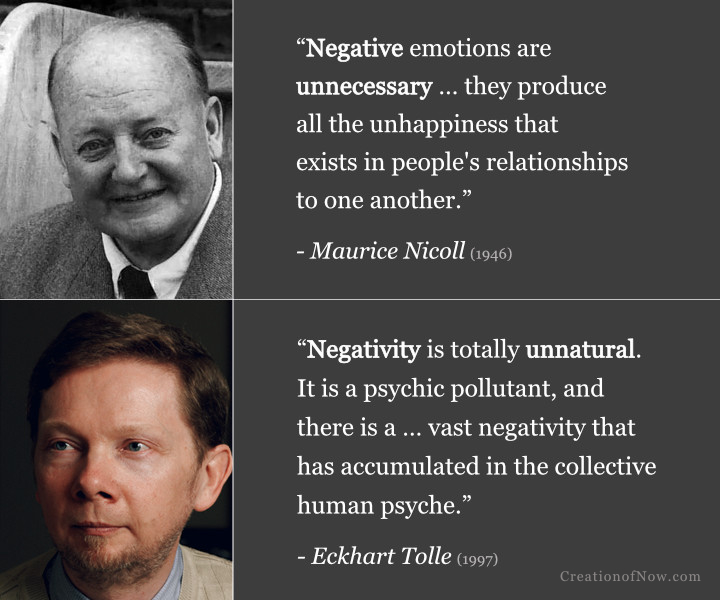

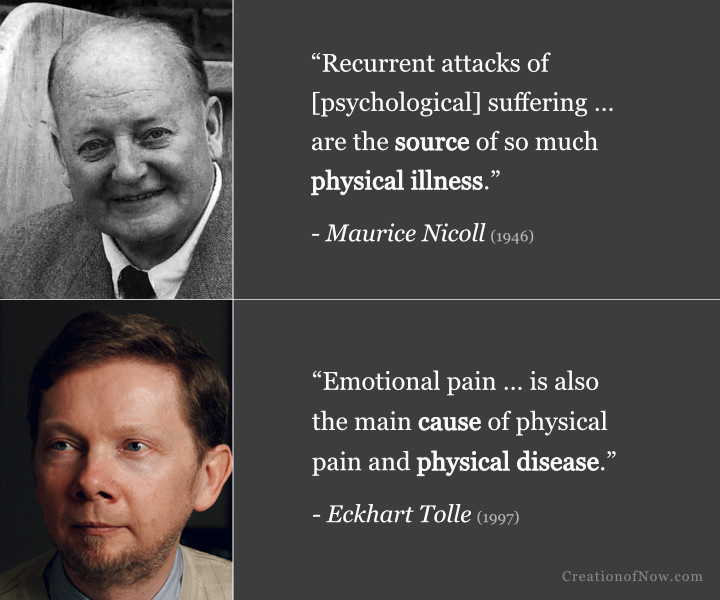

- Addressing negative emotions and states. Nicoll and Tolle both stress we have a particular responsibility to address negative emotions and states, because of how destructive they are to ourselves and others. We should never blame our negativity on anything or anyone else, they say, and should instead take responsibility for our negative states regardless of what happened, others did, or our circumstances. (In this they differentiate negative emotions like unnecessary fear from instinctual fear arising naturally in direct response to physical danger.) Yet people enjoy or take pleasure in their negative emotions, and this ingrained tendency must be honestly observed and overcome. In describing why it’s so important to overcome our negativity, they describe, in similar ways, the numerous adverse effects it has psychologically, physically and socially, including:

- Being infectious or contagious and spreading to others

- Poisoning or polluting the psyche

- Draining and diverting energy

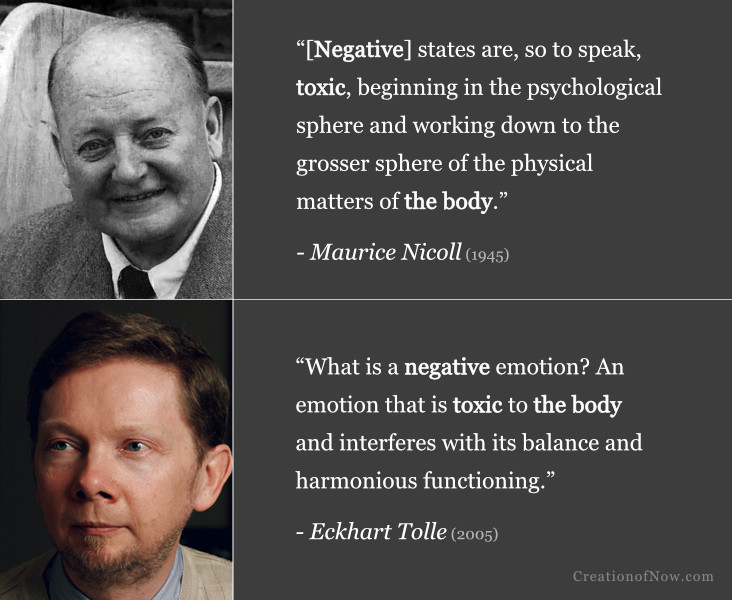

- Depleting our health, being “toxic” to the body, worsening diseases and even causing them

- Causing an underlying sense of grievance and self-pity to accumulate, which creates a perpetual state of misery, strongly identified with, in our thoughts and emotions (both discuss Jesus’ teaching to forgive or make peace with enemies in connection with this)

- This negative “background” can underlie larger outbursts of negative emotions

- Laughing at oneself. The inner shift in our attitude towards external life can bring a welcome quality both describe—the ability to laugh at ourselves. More specifically, to laugh at the unconscious inner states observed in yourself which formerly may have controlled you, but now you no longer identify with. Being able to see their absurdity and laugh or smile at them is considered a good sign. On a somewhat related point, they also suggest that it’s by inwardly seeing and recognising what you are not that you come to recognise who or what you really are.

That is a very condensed summary: I will now examine their treatment of these ideas in close detail, with side-by-side comparisons of how they discuss each point.

Prioritising the inner reality

A recurring self-knowledge idea discussed by Nicoll is that we always exist simultaneously in two worlds or realities: a shared outer reality, and a personal inner world of “thoughts, feelings, sensations… fears, hopes, disappointments” and all variety of inner states. These “two realities” correspond to “outer experience and our inner reaction to it.” While we all see the external world, only we can observe our inner psychological world.[29]

“We live in what is invisible to others. Our bodies are in visible space, but our thoughts and moods and fears and anxieties and feelings are invisible and constitute where we dwell in the psychological world. It is in this psychological world that we really live.”[30]

Of these two “outer and inner” realities, it is “the inner reality” that is “most real,” he asserts, as that is where “you really live all the time, and feel and suffer” and “have your being.” It is “opened up” to us “by means of self-observation.”[31]

Tolle also refers to two realities we inhabit, one within and one without, writing that “primary reality is within, secondary reality without.” He tells us we should “be at least as interested” in what happens within as without, and points to “self-observation” as the means to monitor the states that transpire in the reality within.[32]

“Make it a habit to monitor your mental-emotional state through self-observation. `Am I at ease at this moment?” is a good question to ask yourself frequently. Or you can ask: “What’s going on inside me at this moment?” Be at least as interested in what goes on inside you as what happens outside. If you get the inside right, the outside will fall into place. Primary reality is within, secondary reality without.”[33]

So we can see that to both authors, self-observation is the means to see the inner world or reality, which is considered as or more important than the outer world—Nicoll calls it “most real” and Tolle calls it “primary.”

The inner world/reality is as, or more, important than outer reality, the authors suggest

Inner states attract outer realities

In a quote above, Tolle states, “If you get the inside right, the outside will fall in to place.” This connects to something he discusses elsewhere in the text: “You attract and manifest whatever corresponds to your inner state.” “A strong unconscious emotional pattern,” he also writes, “may even manifest as an external event.” In these cases, he’s writing of how unconscious emotional pain or anger carried within can trigger external conflict—either because it elicits negativity from others who pick up on it unconsciously and react, or because you unwittingly project it onto others and lash out emotionally at them.[34]

Our inner states can attract external situations, both authors convey.

This idea that inner states can attract particular events, and that changing one’s inner states will therefore alter the events of one’s life, is one Nicoll also discussed. “Since our inner life attracts our outer life,” he writes, then “by changing our inner states” we not only change our attitude to external events but can even alter “the nature of the events that come to us.” This links in to a broader teaching he often returned to—that “your level of being attracts your life.”[35]

“To live anyhow in oneself—in this internal vast world accessible only to each person through individual self-observation and always invisible to others—is the worst crime we can commit. So this work begins with self-observation and noticing wrong states in oneself and working against them. In this way the inner life becomes purified and since our inner life attracts our outer life, by changing our inner states, starving some and nourishing others, we also alter not only our relation to events coming from outside but even the nature of the events that come to us day by day. Only in this way can we change the nature of events that happen to us.”[36]

So both authors express the notion that our inner states can attract particular situations, and we can change what we typically attract by changing inner states. In both cases, self-observation, by whatever term, is the means to see and actualise this. [37]

Distinguishing inner reactions from external events

People don’t usually see a clear distinction between their reactions and the events eliciting their reaction, Nicoll and Tolle tell us. Yet by practicing self-observation, we can differentiate events from the psychological reactions they provoke, and recognise we needn’t react in the usual unconscious way. Both cite the example of observing and changing one’s emotional reaction to bad weather to make this point.

We must learn to distinguish situations from our reactions to them, Nicoll and Tolle tell us.

Nicoll explains that most people “take life and their reactions to life as the same thing” or “take life-realities” and their “reaction to them as the same”—yet “they are not the same.” A “mechanical man” does not “observe how he takes events,” and so “does not realise he can react to them in a different way.” To distinguish events from one’s reactions to them, “one has to be able to see the event and at the same time see one’s mechanical reaction to it” in order to “separate from your reaction to it.” This requires “the power of observation so that one is separated from the continual effect of life coming in and reacting always in the same mechanical way”. Then we can recognise we “need not take a life-event always in the same way” but can instead “take life, events, in a new way” and respond “in a different way.”[38]

In a similar vein, Tolle writes that, due to a “lack of self-awareness,” some people “cannot tell the difference between an event and their reaction to the event” or, similarly, the human ego “cannot tell the difference between an event and its reaction to that event.” He likewise points to self-observation as the solution, suggesting it is necessary to reach the point where one can “become present enough to look within” and “disentangle” their “reaction from the event and observe them both.”[39]

Reactions to the weather

Nicoll gives the example of a thunderstorm to explain this idea, indicating people tend to see a “storm, which is part of outer life at the moment, and is a neutral, impersonal thing, and their mechanical reactions to it, which are personal, say, alarm” as “identical” but really an “incident in outer life, such as a thunderstorm, is not the same as their mechanical reaction to it.”[40]

Tolle also explains this idea by pointing to bad weather: “The ego cannot distinguish between a situation and its interpretation of and reaction to that situation. You might say, ‘What a dreadful day,’ without realizing that the cold, the wind, and the rain or whatever condition you react to are not dreadful. They are as they are. What is dreadful is your reaction.”[41]

Both use the example of inclement weather to illustrate separating our reactions from the conditions prompting them.

Thus both authors point to using self-observation to separate, differentiate or distinguish one’s reactions to events, from the events themselves.

Reacting negatively to others

This idea of not reacting unconsciously to outer events also, of course, includes how we react towards other people we interact with. Nicoll and Tolle have much in common to say about this in a broader sense, some aspects of which I’ll discuss in detail later.

I’ll highlight one salient example here: both authors stress we should observe and overcome the reflexive habit of criticising or complaining about other people’s faults—whether openly or mentally—and instead focus on addressing our own unconscious or mechanical reactions towards other people. By reacting so judgmentally towards others, we actually strengthen negative factors in us, they claim.

For example, Nicoll suggest we must “particularly observe silent or expressed criticism of others.” The common tendency to “criticize one another without any restraint” has negative consequences in human relationships and, furthermore, this “mechanical criticism of others produces a great many psychological difficulties in the person who criticizes.” You “must really live more consciously” instead of going along with this factor all the time, he insists, pointing out “it is this complaining itself that you have to notice in yourself and not what you imagine causes it.” If you allow such “critical and negative” tendencies to develop unchecked they will “turn on you” and “hinder your own understanding and your own development.” In this respect, “what you do to others, you do to yourself.”[42]

The mechanical/habitual habit of criticising or complaining about others harms us within, Nicoll and Tolle both suggest.

Tolle similarly points out that, “complaining, especially about other people, is habitual, and, of course unconscious,” and “whether you complain aloud or only in thought makes no difference.” This is “one of the ego’s favorite strategies for strengthening itself,” he claims, and having resentment about other people’s faults and “applying negative mental labels to people … is often part of this pattern.” We need to notice and become aware of this and interact through “being conscious” instead of having the unconscious “compulsion to react” this way. It is “the unconsciousness in you” that cannot overlook “unconsciousness in others,” he suggests. “And what you react to in another, you strengthen in yourself.”[43]

I’ll return to the broader theme of overcoming the tendency to react with negative emotions further on, as both authors emphasise the importance of this in many corresponding ways.

Fault-finding: the log in your own eye

Nicoll and Tolle quote the same parable of Jesus in connection with their critique of the habit of fault-finding. They suggest the unconscious or mechanical habit of finding fault with others is the subject of the parable of the mote and the beam, which is spoken by Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew.[44]

They cite the same Gospel passage to exemplify the need to overcome our fault-finding tendencies

Tolle writes that Jesus refers to the “unconscious egoic pattern” of “faultfinding” in this Gospel passage:

“… the egoic compulsive habit of faultfinding and complaining about others. Jesus referred to it when he said, “Why do you see the speck that is in your brother’s eye, but do not notice the log that is in your own eye?”[45]

Nicoll mentions the same passage a number of times; he also links it to our critical tendencies of “finding fault with everyone else” which arises due to our “general lack of consciousness” from not observing ourselves.

“‘Why beholdest thou the mote that is in thy brother’s eye but considerest not the beam that is in thine own eye?” (Matt. vii.3).’

Now you will admit that this [passage] is a pretty good example of what the Work says about observing yourself instead of finding fault with everyone else. In this brief parable, it is implied that you should really begin to observe yourself … before you criticize other people.”[46]

Note that, in connection with the above points, the authors also discuss the closely-related notion, covered in a previous article, that we can project our unobserved traits onto others.

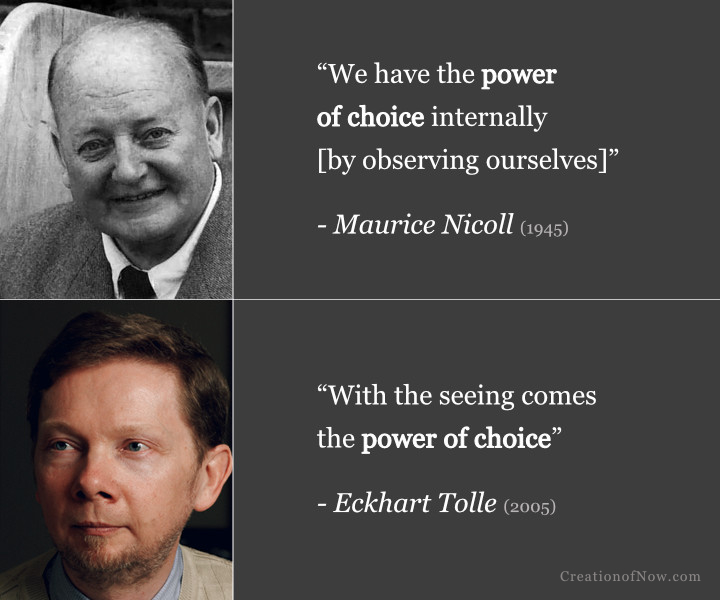

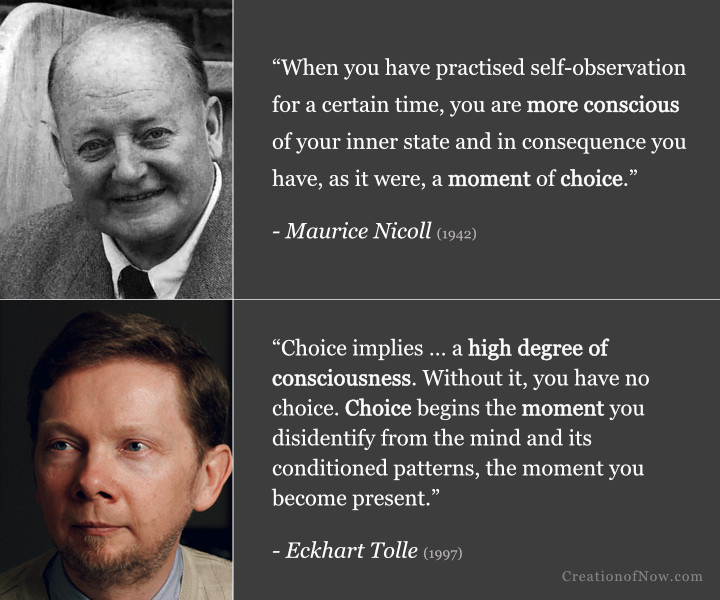

Inner freedom, peace and choice

By becoming conscious of our habitual reactions to life, we gain a new “power of choice” over how we respond internally and externally, the authors say, and a sense of inner freedom and peace that’s independent of external conditions.

The power of choice

“The power of observation” gives you a “moment of conscious choice,” over your habitual reactions to life, writes Nicoll. By observing ourselves, we gain “the power of choice” not to consent to, identify with, or be “dragged down” by inner states. Being “more conscious of your inner state” grants you “a moment of choice” internally; otherwise we just react automatically according to “long-established associations.” People can gradually awaken, and reach a higher state of consciousness, by making the “inner choice” not to “go with” the unconscious inner states they observe—and instead discard them.[50]

Describing the observation of oneself, Tolle similarly conveys that “with the seeing comes the power of choice” and “you realize that you have a choice”—namely, to drop the patterns of unconsciousness you see. This inner choice only begins “the moment you become present” as “choice implies consciousness,” he explains; without this degree of consciousness you are too unconscious in the moment and so “have no choice” but to think, feel and act according to your conditioning. This last statement appears under the subheading “The Power to Choose”.[51]

Inner freedom and peace

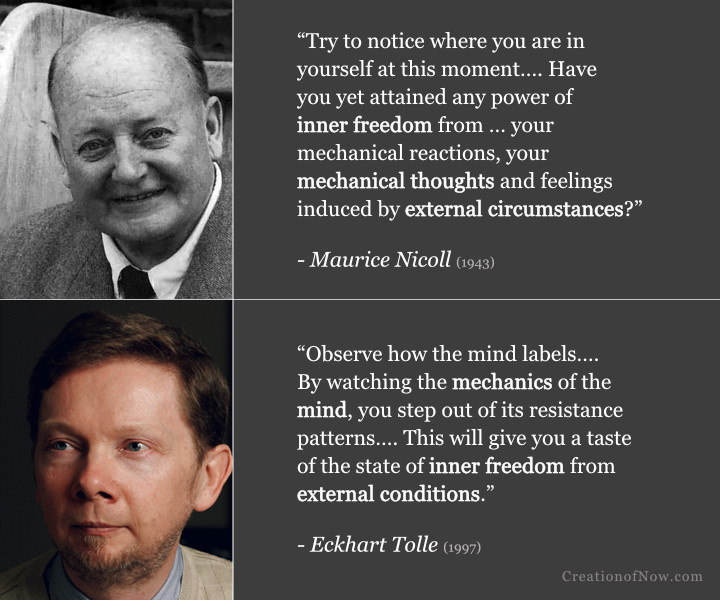

Nicoll and Tolle both write of the “inner freedom” and peace that comes from consciously watching and not identifying with inner states—so that one isn’t controlled by them or events that elicit them. They describe how this brings inner freedom and peace—a conscious state that’s independent of external circumstances and arises from one’s inner being.

For example Nicoll writes that by observing thoughts and feelings in the moment, you can attain “inner freedom … from your mechanical reactions, your mechanical thoughts and feelings induced by external circumstances”. One can deal with daily events “consciously instead of mechanically” and find an “inner peace” that’s “independent of what happens to you”.[52]

Similarly, being conscious in the moment “prevents you from losing yourself in thinking, in emotions, or in external situations,” Tolle suggests. By observing “the mechanics of the mind” in the present moment, you can step out of “resistance patterns” and taste “the state of inner freedom from external conditions, the state of true inner peace”.[53]

Observing our mind and reactive patterns can bring us “inner freedom” from external conditions.

Both link inner peace to one’s true self or being. Nicoll writes of a genuine inner peace arising from one’s “inner being,” or “Real ‘I’” that’s “independent of external things” and events. He links such inner peace to “the peace passing all understanding” mentioned in the New Testament.[54]

Tolle also writes of a “deep inner peace,” arising from your “true nature” or “Being” that’s not dependent upon outer conditions or “some secondary source.” He cites the same passage about “the peace of God, which passes all understanding” to describe such peace.[55]

Personal responsibility for inner states

Consciously observing psychological reactions entails taking responsibility for one’s inner state irrespective of circumstances, we are told. Those who become more conscious are said to acquire greater inner responsibility. Nicoll and Tolle insist any real change to one’s level of consciousness, life and outer conditions needs to start here, as our inner state affects others and the world.

Taking responsibility for your psyche in the moment

Nicoll and Tolle indicate we need to take responsibility for our inner state at any given moment. More broadly, they also write of being responsible for one’s “inner space” or “psychological world” to address unhappiness in us and the world.

The “widespread modern unhappiness” which is “characteristic of modern times” is due to a “lack of psychological responsibility, to ourselves and others,” writes Nicoll. You must be “responsible for your inner states” or “responsible for your own states” which begins when one is responsible for “the state one is in at any moment”. In other terms, we must “become more responsible” for our inner “psychological world” or “psychological space” (phrases he uses interchangeably with “inner space”)[56] of thoughts and feelings. “This can be called living more consciously.”[57]

Tolle also writes of the need to be responsible for your own psychological “inner space” and “inner state”, indicating “your unhappiness is polluting not only your own inner being and those around you but also the collective human psyche.” The world’s condition is caused by “millions of unconscious individuals not taking responsibility for their inner space” and “creating unhappiness”. To end the “misery,” he says, “you have to start with yourself and take responsibility for your inner state at any given moment”.[58]

More consciousness means greater responsibility

Those who are more conscious or awakened should recognise the need to take on more inner responsibility, the authors suggest.

To do the inner work of self-change you must become “responsible to yourself,” explains Nicoll. You “begin to have a new responsibility” in life where you are “internally responsible” “for what you are.” You understand and recognise you cannot indulge in negativeness and behave or react however you wish because “if you make no effort to change … everything will repeat—day by day—and life by life”.[59]

Tolle also points out that “with the grace of awakening comes responsibility.” Those who become more conscious have a “responsibility … not to create further pain” for themselves or others and should strive to bring “light into this world” instead. Only by addressing emotional pain in oneself can we “end the misery that has afflicted the human condition for thousands of years.”[60]

Addressing negative emotions and states

We have a particular responsibility to address negative states, according to Nicoll and Tolle. In their discourses on the need for inner responsibility, they place the greatest emphasis on addressing thoughts, emotions and states which are negative in nature. This is a major theme in their work overall and there are many ways that they correspond in discussing it.

Observing and ceasing to identify with negative states—and thereby depriving them of energy—is the primary method they put forward for overcoming them. I’ve already discussed their practical advice on how to observe and disidentify from inner states more broadly, so I won’t revisit that in detail here. However, just to give some context, here is a passage where Nicoll discusses that general idea:

“Since negative emotions are the greatest wasters of energy and have so many other destructive effects upon us, it is of the greatest importance to try to prevent force from continually going into them. This will always happen if we identify with our negative states. That is why it is so important to try to separate from a negative state, not to go with it, not to consent to it, with the mind at least. For if both the mind and the emotions consent then there is full identification and a full influx of energy into the negative state. That is why we must try to starve our negative states because the more we nourish them, secretly approve of them and secretly enjoy them, the more energy they will insist on taking from us. A person who is a slave to his or her negative emotions is actually a slave, only the trouble is that we very easily enjoy different forms of slavery, not recognizing that we are really in prison. But it is useless to speak of all this if you do not yet know what it is to observe negative states and negative remarks in yourselves.”[61]

In a previous article, I showed how Nicoll and Tolle both claim that we carry some kind of psychic factor inside us expressing negative emotions and bringing unhappiness.

In Tolle’s work, the “pain-body” is the culprit. This is said to be an energetic parasite accruing the residue of all our unconscious emotional pain, which grows within us from childhood. It generates negative emotions throughout our lives to feed on their energy to renew itself. It is “the living past in you.”

Nicoll, decades earlier, described the “negative part of the emotional centre” as an unnatural psychic disease acquired by infection in infancy and growing within us thereafter. It gives rise to negative states which nourish it—feeding upon and storing their energy. This emotional suffering is also stored in our “time body” which carries our “living past.”

I don’t want to revisit these concepts in detail now; I only mention them for context, as the terms will occasionally come up. But they’re not the focus.

Rather than returning to their psychological “origin theories” for negative states, here I’ll focus on what they say about negative states in themselves: why they’re such a problem that needs to be addressed. There are many corresponding characteristics and effects they describe negative states having on us; these can be considered independently of the underlying mechanisms behind their expression.[62] In any case, the rationale for dealing with negativity remains the same.

So I will explore what they say in common about the particular harm negative states do to us and others and why it’s so important to overcome our tendencies to react negatively to life. They cover similar ground on how these states operate, the forms they take, their destructive effects, and the benefits of becoming free of them.

We should never justify or blame negative states on external causes or other people, Nicoll and Tolle say. These states are destructive in nature and a prime cause of unhappiness— skewing our perception for the worse, and giving rise to many unpleasant reactions and behaviours. They not only poison or pollute our psyche, but spread misery and unhappiness to others and the world too. They describe a number of comparable adverse effects that negativity has psychologically, physically and socially, and encourage us to address it for our own sake and the benefit of others too.

In line with the general focus of this article, consciously shifting our inner approach when negative states occur—to take personal responsibility for our state instead of blaming it on other people or situations—is a major theme they often return to.

Types of negative states

Negative states, as will be discussed here, includes thoughts, emotions and moods—essentially, any form of psychological negativity. The authors mention various types of inner states they describe as negative and indicate we should deal with. These include:

- Hatred[63] [64]

- Anger (and rage, irritation etc.)[65] [66]

- Fear[67] [68]

- Resentment[69] [70]

- Depression[71] (and discontent)[72] [73]

- Jealousy[74] [75]

- Envy[76] [77]

- Dislike[78] [79]

- Anxiety (and worry)[80] [81]

- Violence (and destructiveness)[82] [83]

- Self-pity[84] [85]

- Grievance(s)[86][87]

They also describe how negativity, discontent or unhappiness can carry on in the “background” of ourselves—often linked to an abiding sense of grievance, resentment or “self-pity,”—an aspect I’ll explore further on.

In all cases, this psychological negativity is viewed as unnecessary, useless and even unnatural, serving only to bring misery, unhappiness and suffering to ourselves and, quite often, others too. We would all be better off without negative emotions and states, they insist. [88] [89]

Natural instincts vs unnecessary negative emotions

Nicoll and Tolle distinguish unnecessary negative emotions from instincts that prime the body to deal with immediate threats. For example, they separate “instinctive fear” or “primordial fear,” respectively, from emotional fear. The former is a natural response to real and immediate danger, whereas emotional fear comes from our thoughts or imagination about possible threats or past/future problems. Both compare human behaviour to that of an animal to show the difference—Nicoll uses the example of rabbits, Tolle uses ducks.

Instinctive/primordial fear is a natural response to immediate danger—unlike emotional fear which involves the mind or imagination, they tell us.

Nicoll suggests that instinctive emotions are “present in us and in all animals” and appear as a “direct response to a sensory stimulus” for our survival, whereas negative emotions are produced unnecessarily by human imagination. Rabbits instinctually feel fear and hide in the face of danger, he explains, but the fear passes when the threat does; they do not spend their lives “imaginatively afraid” about all the bad things that could happen to them. They lack the human capacity to produce emotions out of imagination. “Instinctive fear,” he makes clear, is “stimulated only by the direct sensory impression of danger” and prepares our bodies “either for attack or for defence,” as it does in animals. Emotional fear, on the other hand, “arises from the manifold activities of the negative part of Emotional Centre” and “is not based on an actual sense-given situation.” Animals do not have this problem: “Just imagine if rabbits had emotional imaginative fear!” he remarks, “They would never appear above ground.”[90]

Tolle likewise distinguishes instinctive responses for the body’s survival, which human beings experience as animals do, and negative human emotions caused or influenced by thinking. Instinctive reactions like “primordial fear” and “primordial anger” are a direct “instinctive response … to some external situation” to prepare the body “for fight or flight,” he explains, but many unnecessary emotions appear in people in reaction to their thinking or “the filter of thought”. This produces fear as a “psychological condition … divorced from any concrete and true immediate danger…. This kind of psychological fear is always of something that might happen, not of something that is happening now.” To illustrate the difference between thought-influenced human emotions and the more natural instinctive kind, he describes more than once how ducks quickly become tranquil again after a brief skirmish in the pond, “as if nothing had ever happened.” But “if the duck had a human mind, it would keep the fight alive by thinking, by story-making” for “days, months, or years later.” He calls this tendency the “emotional thinking of the ego”. “You can see how problematic the duck’s life would [then] become,” he remarks, “But this is how most humans live all the time.”[91]

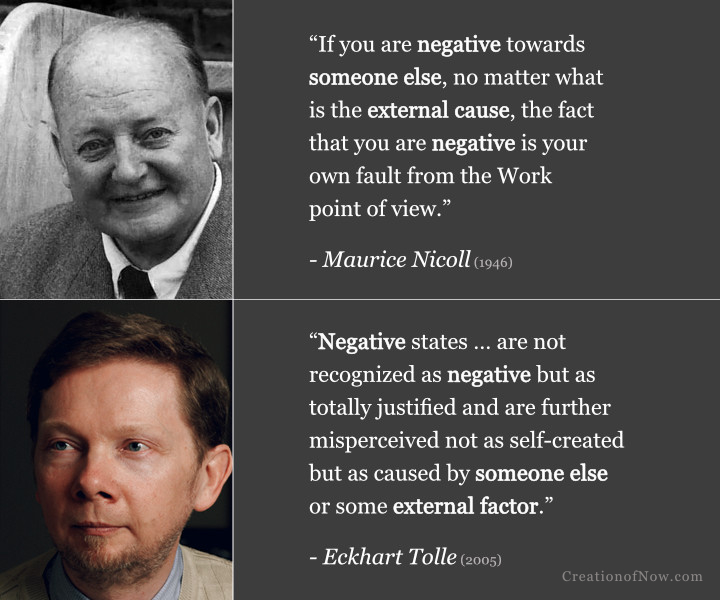

Not blaming negativity on external causes

If we are to overcome unnecessary negativity we have to stop making excuses for it, we are told. Nicoll and Tolle both insist we should take responsibility for any negativity within us, regardless of what happened, others did, or our outer circumstances. We cannot justify our negativity by what someone else did or blame it on any “external cause” or “external factor.”

A negative state should not be blamed on someone else or any other external cause, Nicoll and Tolle make clear.

Nicoll frequently writes about addressing negative states, emotions or thoughts and stresses the need to feel personally “responsible for them.” “No matter what happened, what someone said, what someone did, we have to become responsible for our negative states—ourselves,” he writes. This means realising “it is always our own fault if we are negative” and we have “no excuse for it” and must not justify it by blaming it on others or some “external cause”. “When people indulge habitually in negative states without for a moment seeing what enormous harm they are causing to themselves,” Nicolle writes, then “they have no idea about their own responsibility to themselves.”[92]

“If you are negative towards someone else, no matter what is the external cause, the fact that you are negative is your own fault from the Work point of view.”[93]

“No matter what happened, what someone said, what someone did, we have to become responsible for our negative states—ourselves…. Of course, if you secretly love being negative and indulging in unpleasant emotions, then I can only say that whatever else you indulge in secretly this is the worst thing of all.”[94]

“When you realize that whenever you are negative it is your own fault, whatever the external cause, you begin to have a completely new orientation formed in you.”[95]

Tolle likewise points out that “you are responsible for your inner space; nobody else is” and you thus have a responsibility not to harbour “any negative inner state” as these will “pollute” your inner being. You must relinquish any “victim identity” which is the belief that “other people and what they did to you are responsible for who you are now”— you cannot justify negative states as being “caused by someone else or some external factor”. Since “you are responsible for your inner space now – nobody else is” you must take “responsibility for your state of consciousness” and “take responsibility for your life” which means not giving “negativity” or unhappiness “a dwelling place inside you.”[96]

“Negative states such as anger, anxiety, hatred, resentment, discontent, envy, jealousy, and so on, are not recognized as negative but as totally justified and are further misperceived not as self-created but as caused by someone else or some external factor. “I am holding you responsible for my pain.” This is what by implication the ego is saying.”[97]

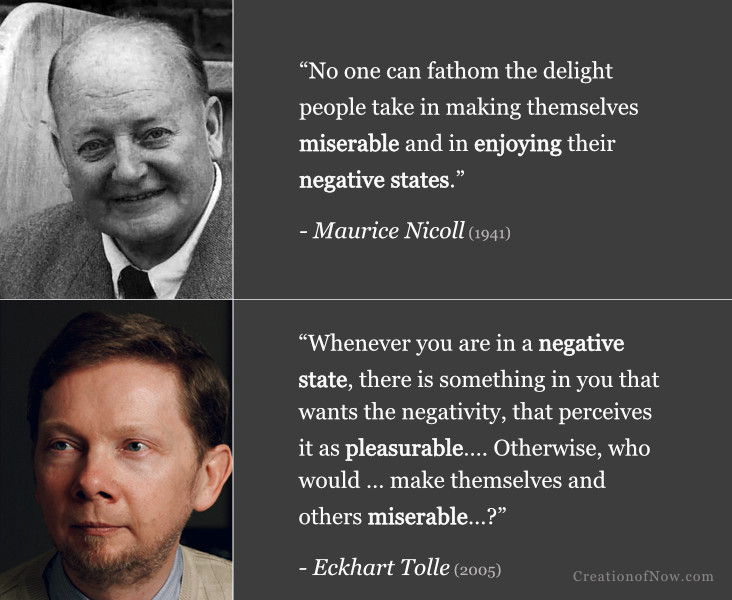

The enjoyment of negative states

One of the chief hurdles to taking responsibility for, and rooting out, negative emotions and psychological suffering, is that many people don’t actually want to give it up. Nicoll and Tolle both discuss the “curious” or “peculiar” way people enjoy or take pleasure in negative states and “indulge” in them and the unhappiness they bring. They advise us to closely observe this tendency in ourselves.

“People love their negative emotions,” writes Nicoll, and “will not let go of them easily.” “People love being negative, feeling they suffer” and “indulge so frequently in negative emotions.” “No one can fathom the delight people take in making themselves miserable and in enjoying their negative states,” he remarks. “Other emotions become dull, compared with the curious delights of being negative.” The habitual enjoyment of negative emotions is “comparable to a fascinating drug” that “gets a hold of a person.”[98]

“One reason … people like to be negative,” he writes, is “because then they can hurt everyone so easily” and emotionally “infect” others. “This ability to affect others gives the negative person a sense of power.” But this apparent enjoyment is actually “slavery” to negative states—which “always lead to internal unhappiness” and have “destructive effects upon us.” Therefore, “no one who is negative can have any real feeling of happiness except from love of being negative.” “But if you want the state and enjoy it in this curious way that we do—that is, love our negative states—then how can it disappear?” Thus “the enjoyment of negative states must be observed sincerely,” if one is to become free of negativity.[99]

Many people enjoy or take pleasure in negative states, they tell us.

In a similar vein, Tolle indicates that “whenever you are in a negative state, there is something in you that wants the negativity, that perceives it as pleasurable.” Whenever you seek this “emotional negativity” and unhappiness, and it takes over, then “not only do you not want an end to it, but you want to make others just as miserable as you are in order to feed on their negative emotional reactions” as well. Negativity can often become compulsive, and then “it is not so much that you cannot stop your train of negative thoughts, but that you don’t want to.” He describes this condition as an “addiction to unhappiness” afflicting most of humanity.[100]

It is the ego (and pain-body) that wants to “indulge in unhappiness” and negative emotions, he explains, and “takes pleasure in it”, as this “suffering or negativity is often misperceived by the ego as pleasure.” Yet “such states are indeed pathological,” he writes. They “are forms of suffering and not pleasure.” While someone may derive “a false sense of pleasure” from their “compulsive thinking” of an “often negative nature,” this is a “pleasure that invariably turns into pain.” Tolle likewise suggests that the psychological attachment to emotional pain must be closely observed if one is to break free of it:[101]

“Observe the attachment to your pain. Be very alert. Observe the peculiar pleasure you derive from being unhappy. Observe the compulsion to talk or think about it. The resistance will cease if you make it conscious.”[102]

Negativity’s adverse effects: physical, psychological and social

Nicoll and Tolle describe similar adverse effects negative states bring physically and psychologically. Negativity pollutes our inner psyche; drains our energy and debilitates our health—worsening diseases and even causing them. Furthermore, our negativity infects others too, spreading misery through wider society. These are important reasons to take responsibility for, and address, our negative states, they maintain.

Tolle suggests a “highly conscious” person is psychically immune to being affected by the negativity on others, while Nicoll implies a “fully conscious” person cannot be made negative; he points to the need to become “hermetically sealed” psychologically—to prevent external events and people from provoking negativeness in you.

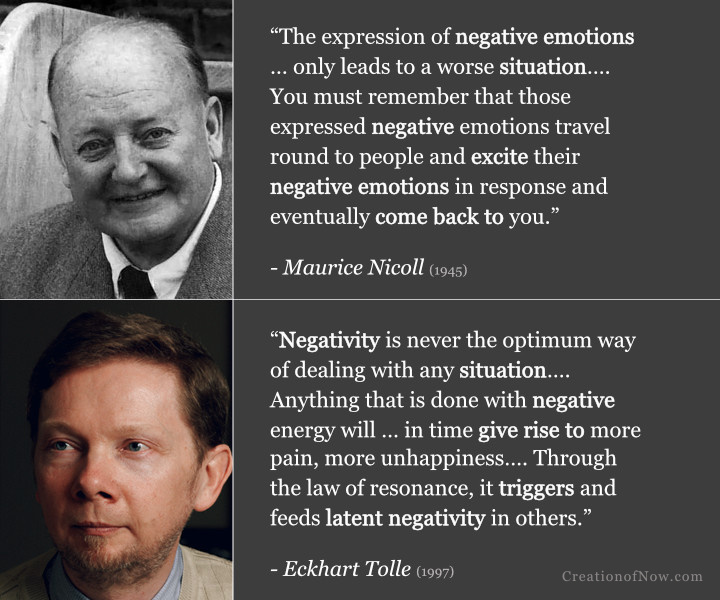

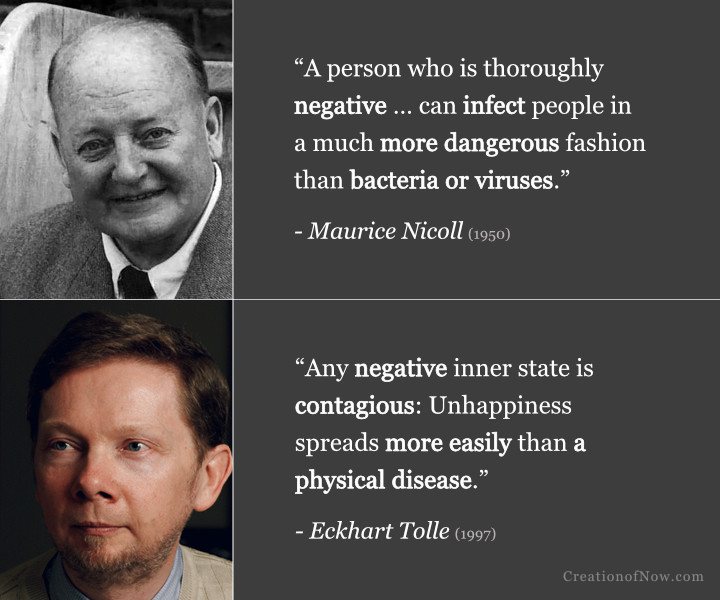

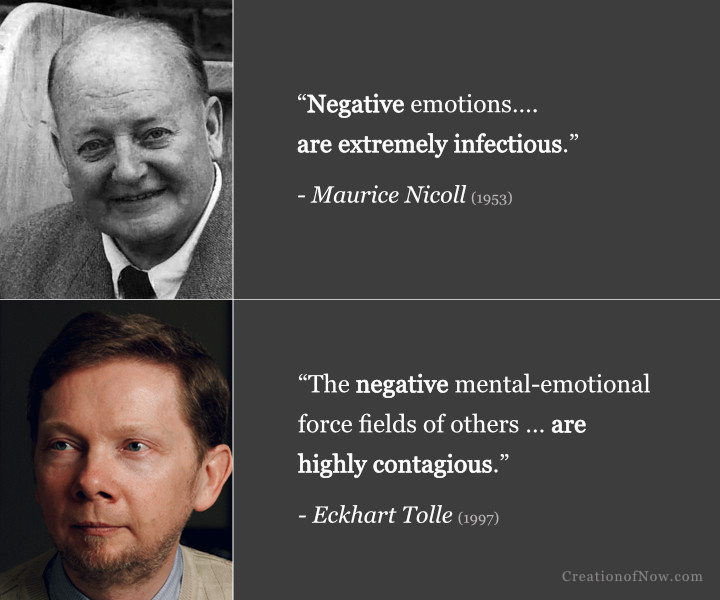

Negative emotions are contagious or infectious

Both authors express the idea that negative emotions and states are infectious or contagious. Negativity spreads more easily or dangerously than a regular disease, they say— by exciting or triggering the same state in others (an effect some enjoy). This capacity to infect other people is a major reason to become “responsible for” one’s own inner negative states and deal with them.

Nicoll describes negative emotions as “extremely infectious”. Their power and capacity to “infect everyone” makes them “more dangerous” than a “physical infection.” Just one “negative person” can infect “a lot of other people,” he claims, giving estimates as high as “a hundred” or “a thousand”—and possibly “many more” if they speak publicly.[103]

Tolle similarly describes negative emotions and states as “highly contagious”, writing that “unhappiness”—“a generic term”, he says elsewhere, “for all negative emotions”— “spreads more easily than a physical disease”. A negative emotion “infects the people you come into contact with” as well as “countless others you never meet” through a process of chain reaction. Ultimately, one’s negativity and unhappiness pollutes “the collective human psyche,” he claims.[104]

Becoming impervious to negative states

Psychic negativity isn’t spread exactly like a foreign pathogen however (which typically enters, has a period of activity, and then is eradicated). Rather, a person’s negativity triggers or excites the same capacity already existing in others. For this reason, negativity is never a good way to deal with a situation, although these states can still have bad effects even if we say or do nothing to show them outwardly. While a physical disease is usually addressed automatically by a healthy immune system, we won’t become invulnerable to the negativity of others—and cease spreading it ourselves—unless we actually change and become more conscious in life. Nicoll writes of having our psychology “sealed” against negative influences, while Tolle writes of enhancing your “psychic immune system” to protect yourself from the negativity of others. In both cases, this protection comes about by living more consciously.[105]

Nicoll describes how our negative emotions “travel round to people and excite their negative emotions in response’ when we express them, and this “only leads to a worse situation.” Our negativity will not only “poison ourselves” but will “poison other people” too. It is therefore important to “deal with” and “feel responsible for” any negative emotions or thoughts occurring internally—even if we “say little or nothing externally” to express them and “appear smooth outwardly.” A “fully conscious” person is incapable of violence produced by negative emotions, he suggests. Becoming “more conscious of yourself” involves learning to “become hermetically sealed towards negative emotions, towards the ordinary events of life” so that outer influences do not “plunge us into unhappiness” or “into negativeness.”[106]

Being negative makes a situation worse, elicits negativity in others, and ultimately brings more suffering back to you, Nicoll and Tolle convey.

Tolle similarly writes that “negativity is never the optimum way of dealing with any situation.” “Any negative inner state” we experience “triggers and feeds latent negativity in others” through the law of resonance—unless other people are themselves “immune,” which only occurs if they are “highly conscious.” Thus people need to be “responsible for” what happens in their “inner space” and should clear the “inner pollution” caused by negativity, which also affects others. Through having a higher “mode of consciousness” in life, it is possible to enhance your “psychic immune system,” he claims, which “protects you from the negative mental-emotional force fields of others, which are highly contagious.”[107]

Psychic pollution or poison

A point touched upon above is that apart from being infectious or contagious, negativity is unnecessary and unnatural and creates a kind of psychic pollution or poison in us, which accumulates. Both authors describe this idea that negativity contaminates the psyche and is unnecessary and unnatural.

Nicoll describes negative emotions and states as inner psychological “filth” “mud” “mire” “dirt” and “mess.” Indulging in them makes us “filthy” inside: “The greatest filth in a man is negative emotion”. These states are unnecessary and unnatural, acting like a “poison to us” and by enjoying them you are “destroying yourself inside—you are simply poisoning yourself”. Relatedly, he also claims that people accumulate “a mass of heavy, dense, negative material” or “wrong or evil psychic material” within by having unrestrained negative attitudes and emotions which “produce all the unhappiness that exists in people’s relationships”. [108]

Tolle, in a similar vein, suggests negativity or “unhappiness” forms an inner psychic pollution or mess, which pollutes not just oneself but other people and the world. It is “totally unnatural.” He associates this “psychic pollutant” with poison, stating there is a “deep link between the poisoning and destruction of nature” and the negativity in people. This pollution accumulates within, and a “vast negativity … has accumulated in the collective human psyche”.[109]

Draining and diverting energy

As well as contaminating ourselves and others, our negative emotions cause a severe drainage or “leakage” of our energy/force, which has adverse psychological and physical effects.

Nicoll indicates negative emotions, states and thoughts (“inner talking”) all drain, absorb, waste, take or cause a “leakage” of one’s force or energy. By wasting and misusing energy, these “useless” and destructive states can make a person become ill. With self-observation we can see how negative states drain us: the process is likened to bleeding or slowly dripping from a cut artery. This is psychologically debilitating and a major hindrance to inner development (for which energy must be preserved and refined). [110]

Tolle likewise writes that negative thinking causes a serious drainage or leakage of vital energy and is a useless and harmful process; one can discover this to be true by observing their mind. Negative emotions can also block and disrupt the “energy flow through the body”, deplete it, and leave it more susceptible to illness.[111]

We can observe for ourselves how a negative state or thought saps our force/energy

Physical Illness

Negative states contribute to physical illness in multiple ways, Nicoll and Tolle suggest. Negativity depletes our body and its natural defences by draining energy, leaving us susceptible to disease or worsening existing ones. Furthermore, negative states are themselves toxic or poisonous to the body, so their very presence may harm us physically too. A negative state may itself even cause or manifest a particular disease, they suggest. Both claim that most illnesses have a psychological or emotional cause.

Worsening illnesses, depleting health

Negative emotions, states or thoughts can worsen, animate and prolong an illness, according to Nicoll. They can “make the illness worse or more persisting” and cause it to “become exaggerated.” By wasting energy and exhausting you, they also increase the likelihood of becoming ill; they also do this by obstructing and upsetting the normal “distribution of energy” in a person. They “take so much energy and waste it uselessly” that it “exhausts you, wastes your force” and some states can “exhaust and deplete the nervous system.” As a result, you become “depleted in health” and your “general powers of resistance to illness” are diminished. “People often become ill as a result” and “have many illnesses that are unnecessary.”[112]

Tolle also conveys that people who have negative states during illness, such as complaining, feeling self-pity, or resentment,[113] “take much longer to recover” from an illness or cause it to become “chronic”. The “considerable amounts of energy” the ego “burns up” through such states is linked to this effect. Negativity can cause one’s organism to become “depleted” which makes you “much more susceptible to illness;” it can also promote disease by blocking and disrupting the “energy flow through the body.” He points to an increasing recognition of “the connection between negative emotional states and physical disease.” The immune system becomes stronger the more conscious you are, he suggests, and most illnesses “creep in” when we lack a sufficient degree of consciousness or presence.[114]

Toxic to the body

Negative states not only waste energy; they’re also “toxic” to our physical body and “poison” it along with the psyche, Nicoll suggests. The “energy” connected with negative manifestations can “link up with” an illness “and increase it.” And when we “poison our bodies” with negativity “we poison other people” too.[115]

Negative emotions are “toxic to the body,” Tolle also suggests, and interfere “with its balance and harmonious functioning.” Any “emotion that does harm to the body also infects the people you come into contact with,” he writes.[116]

Negativity is toxic to the body, not just the psyche, the authors tell us.

Creating disease

Gurdjieff maintained that most illnesses have a psychological cause and Nicoll reiterates this idea. In addition to worsening illnesses or increasing our susceptibility to acquiring disease, Nicoll claims negative states, emotions and thoughts can directly express themselves as illnesses. He likens negativity to psychological diseases which can “work out into” or “express themselves” materially through the body as “various physical disorders” or illness. Negative emotions may actively make use of stolen psychic energy to “form symptoms” and “animate a new sickness or re-animate old typical illnesses” in people. The toxic chemistry of negativity can work down into “the physical matters of the body” and form a “thick, dead substance” in oneself that induces “attacks of suffering” which causes illness.[117] This occurs largely because we carry tendencies to “enjoy suffering” (see above discussion on this).[118]

Tolle also conveys that negative states, emotions and thoughts not only disrupt the body’s wellbeing but can “create disease in the body.” A strong negative emotion can manifest “indirectly … as a physical illness” or dysfunction and “illnesses and accidents are often created” by “deeply negative and self-destructive” thoughts and feelings. Similar to the Fourth Way idea that most illnesses have a psychological cause, Tolle writes that emotional pain is “the main cause of physical pain and physical disease” and suggests negative thoughts are the “cause of untold misery and unhappiness, as well as of disease”. The body can develop “an illness or some dysfunction” in response to unhappiness caused by the dysfunctional ego which “creates restrictions and blockages in the flow of energy through the body” that the body “cannot but respond to” in a bad way. This negativity occurs because “there is something in you that wants the negativity, that perceives it as pleasurable”.[119]

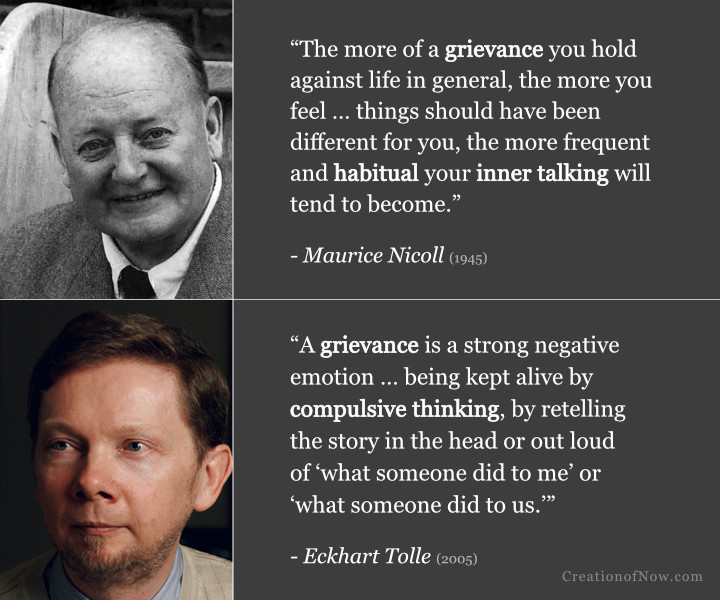

Grievances: our sad songs and stories

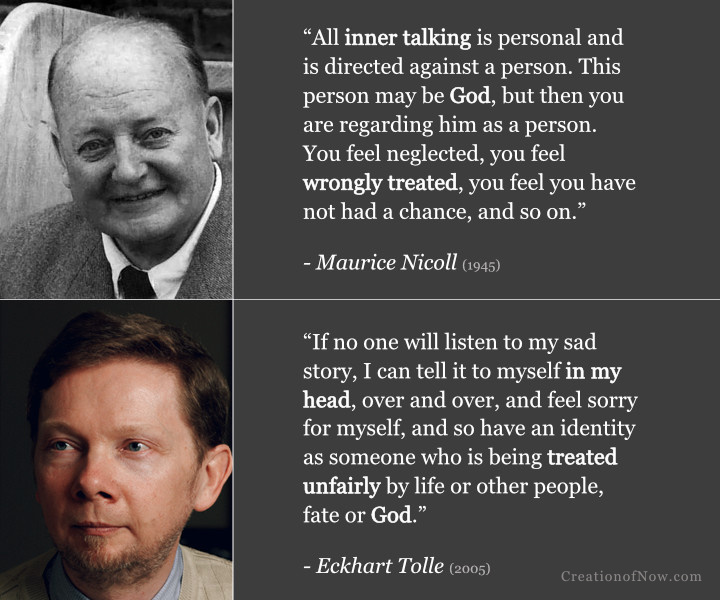

A particularly persistent and underlying aspect of negativity that Nicoll and Tolle often discuss is the sense of “grievance” and “self-pity” people can cling to and sustain, often by thinking and feeling one is ill-treated or hasn’t got what they deserve, and holding things against others. Whether this is real or imagined, there is a pervasive sense of having been treated unfairly by other people or even life itself, fate, and possibly God (both cite all these examples) that dominates the psyche, as one holds onto past resentments. By always dwelling upon and retelling one’s tales of woe—our personalised “sad songs” or “sad stories,” as they respectively call them sometimes—either mentally to ourselves or outwardly to others, we build-up strong negative emotions and a perpetually negative outlook that is strongly identified with, and becomes entrenched.

We must observe and break identification with this tendency, they say, as it holds our inner development back. Doing this involves the inner forgiveness of others. Both link this idea to Jesus’ teaching about loving, or making peace with, one’s enemies. But real forgiveness can only come about by actually observing the grievance process occurring in one’s thoughts, feelings and behaviour, they suggest, and bringing this into the light of consciousness or presence.

Nicoll on the “sad songs” of our grievances

By indulging in “negative thoughts,” Nicoll writes, we “nourish” negative emotions with our “inner talking” formed of “chain after chain of negative thinking”. “Negative thinking with negative emotion is destructively dangerous.” Some people “habitually identify with a gloomy, tortuous, mistrustful class of thoughts” and “take great pleasure” in “thinking negatively” about others. The common habit of holding things “against other people,” leads “to so many negative trains of thought and feeling,” and a “habitually negative person is … always thinking unpleasant things about others … always having some grievance, or some form of self-pity, always feeling that he or she is not rightly treated.”[120]

This mental monologue is … “directed against” … “a person,” but sometimes “God, or Fate, or Luck.”

In Fourth Way terms, this constant sense of grievance is called “internal considering,” and a major part of it involves amassing complaints that we hold against others—known as “making accounts.” This describes how a person commits to memory every sense that they “are owed” by others and deserve “better treatment, more rewards, more recognition”—and records this “in a psychological account-book, the pages of which he is continually turning over in his mind.” The bad habit of retelling “sad songs” about our lives, drawn from these “inner accounts” of past sufferings is colloquially called “singing your song.” These often-repeated songs, which “express our suffering,” are frequently shared with whoever will listen, but often recur privately in one’s thoughts as inner talking—mental muttering, complaining and brooding that “drags a person down very much because it is basically negative.” These inner songs, often about being “unappreciated, misunderstood, and so on,” are something like “the classical song called ‘Poor Little Me,’” Nicoll writes, and “constantly re-infect [a person’s] inner state.” This can create, “a sort of perpetual secret grievance that may spread over and darken all one’s inner life.” This mental monologue is always “directed against” someone; usually “a person,” but sometimes “God, or Fate, or Luck.” “The more of a grievance you hold against life in general … the more frequent and habitual your inner talking will tend to become.” This has a “very great psychological consequence,” as it constantly drains our energy and swamps us with negative emotion.[121]

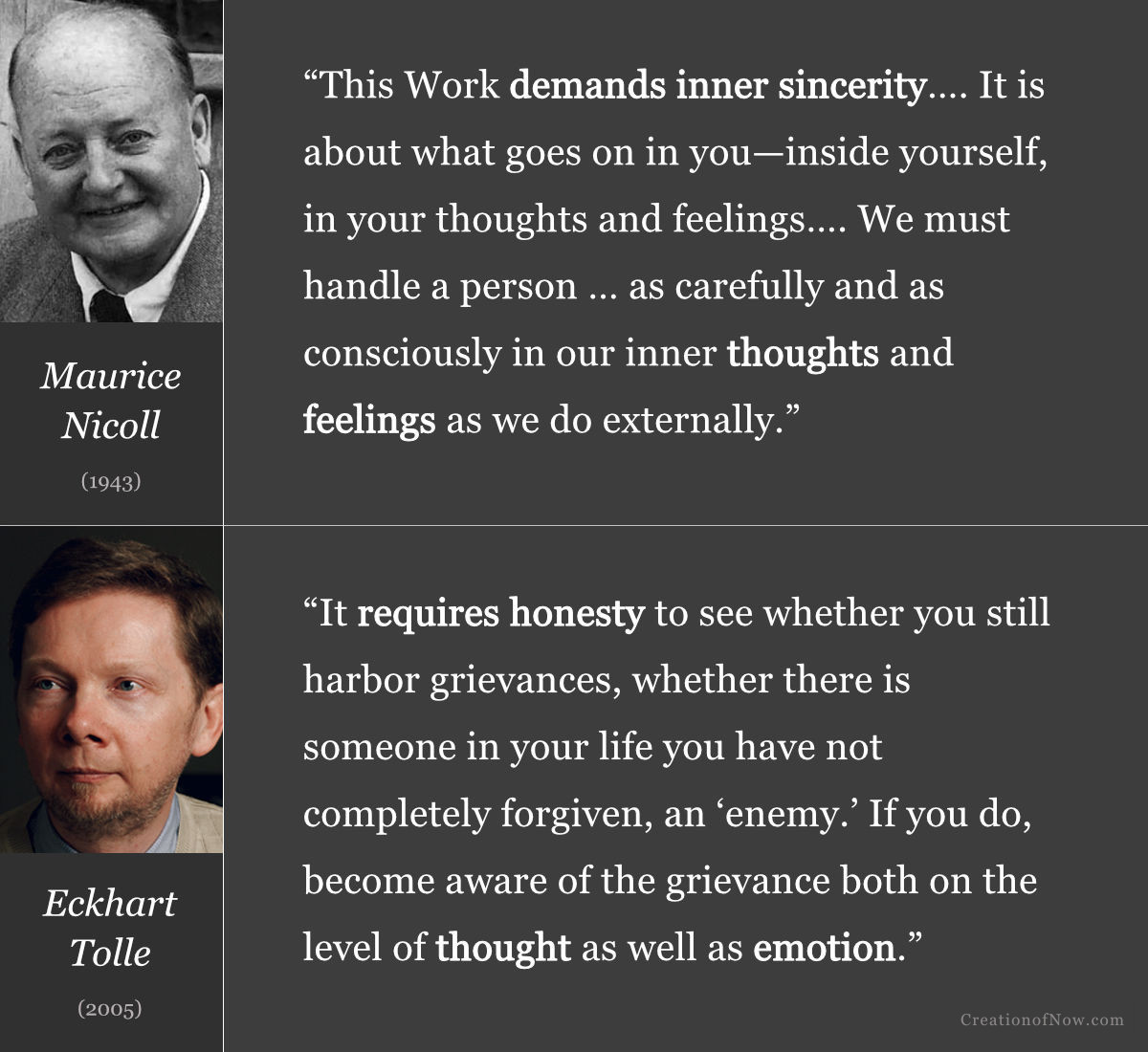

You must have the “inner sincerity” to observe negativity “in your thoughts and feelings”…. Becoming conscious of, and cancelling, [psychological] debts, he suggests, is “the inner meaning of Christ’s remark that one should make peace with one’s enemy.”

We must observe this process seriously and stop identifying with and indulging it—and starve it instead, Nicoll says. This entails cancelling the psychological feeling “you are owed by other people,” which only sustains the misery and holds back inner growth. You must have the “inner sincerity” to observe negativity “in your thoughts and feelings” to carry this out, he explains, and actually “see through self-observation … where you are caught and held down by the making of inner accounts,” and “observe … and notice what [your] inner talking is saying.” Seeing this, without justifying it, brings the process “into the light of consciousness.” This naturally diminishes “the feeling that other people owe us” and you may “feel a release” from the negativity. Thus sincere observation, according to Nicoll, allows us to genuinely forgive others through consciously seeing and cancelling the psychological “debts” we hold against them. This inner process of becoming conscious of, and cancelling, such debts, he suggests, is “the inner meaning of Christ’s remark that one should make peace with one’s enemy.”[122]

Examples: Nicoll

“The first thing that we must do in regard to inner talking is to observe it and notice what this inner talking is saying. As I said, it is always a monologue. Yet all inner talking is personal and is directed against a person. This person may be God, but then you are regarding him as a person. You feel neglected, you feel wrongly treated, you feel you have not had a chance, and so on…. The more of a grievance you hold against life in general, the more you feel in general that things should have been different for you, the more frequent and habitual your inner talking will tend to become.”[123]

Tolle on the “sad story” of our grievances

Tolle similarly describes humanity’s “addiction to unhappiness” which thrives on emotional negativity and “negative thinking”—which often involves “the voice” in your head “telling sad, anxious, or angry stories about yourself or your life, about other people” and “blaming, accusing, complaining, imagining.” People are usually “totally identified with whatever the voice says”. When you are like this, he writes, “it is not so much that you cannot stop your train of negative thoughts, but that you don’t want to.” These thoughts are said to feed emotional pain which in turn generates more thoughts.[140]

This tendency, he suggests, is often linked to “a grievance” which is “a strong negative emotion … kept alive by compulsive thinking, by retelling the story in the head or out loud of ‘what someone did to me.’” People often create a “victim identity” and “victim story” out of this which they strongly identify with. This brings about the compulsion to tell one’s “sad story” about one’s life to whoever will listen. And if others won’t: “I can tell it to myself in my head, over and over, and feel sorry for myself, and so have an identity as someone who is being treated unfairly by life or other people, fate or God,” explains Tolle. “Many people,” he writes, “complain that others do not treat them well enough. ‘I don’t get any respect, attention, recognition, acknowledgment,’ they say…. Who they think they are is this: ‘I am a needy ‘little me’ whose needs are not being met.’ But holding onto grievances and a victim identity keeps a person trapped in their emotional suffering, he says, and the associated negative compulsive thinking “causes a serious leakage of vital energy.”[141]

“It requires honesty to see whether you still harbor grievances” … operating “on the level of thought as well as emotion” …. Jesus’ teaching to “Forgive your enemies,” is essentially about this inner process, he maintains.

“It requires honesty to see whether you still harbor grievances,” and we have to observe any “grievance pattern such as blame, self-pity, or resentment” operating “on the level of thought as well as emotion” in order to break identification with it and our “victim identity”. “The seeing is freeing,” Tolle writes, and when “you bring in the light” of “Presence” in this way then “your victim identity dissolves.” This is how we forgive—by seeing and “undoing … egoic structures.” Jesus’ teaching to “Forgive your enemies,” is essentially about this inner process, he maintains.[142]

Examples: Tolle

“Seeing oneself as a victim is an element in many egoic patterns, such as complaining, being offended, outraged, and so on. Of course, once I am identified with a story in which I assigned myself the role of victim, I don’t want it to end, and so, as every therapist knows, the ego does not want an end to its ‘problems’ because they are part of its identity. If no one will listen to my sad story, I can tell it to myself in my head, over and over, and feel sorry for myself, and so have an identity as someone who is being treated unfairly by life or other people, fate or God.”[143]

Background negativity underlying reactions

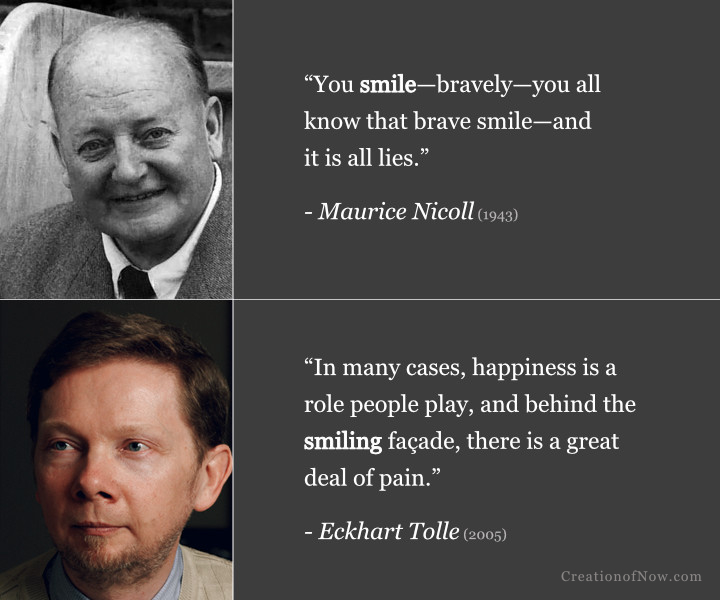

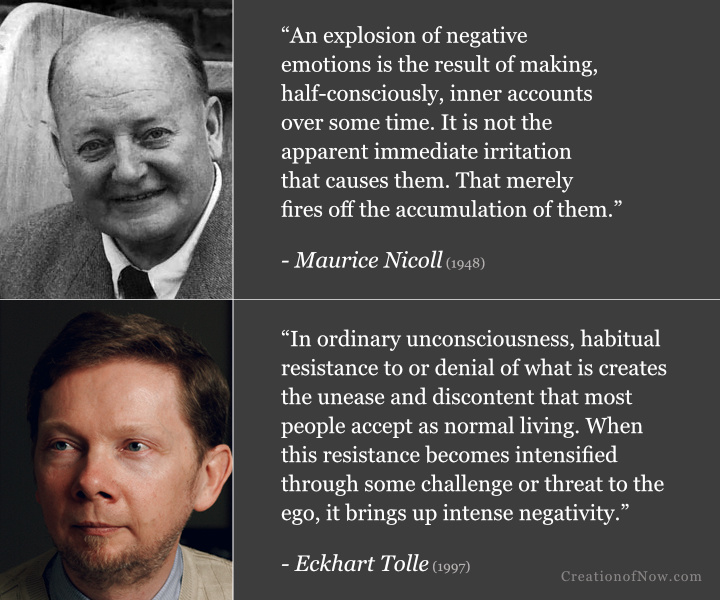

The ongoing process of carrying grievances and resentments described above is part of the negativity, discontent or unhappiness that exists in the “background” of the psyche, Nicoll and Tolle suggest. This low-key negativity can remain hidden behind a calm exterior.

But when we have a major reaction or outburst to a minor event, it can be because this underlying subtler negativity goes unnoticed, accumulates, and then sparks or triggers a bigger reaction. So changing our reactions to life involves not just seeing intense reactions in the moment, but the underlying and subtler forms of negativity that often precedes these.

Nicoll

This unconscious background of negativeness obstructs finer influences from reaching us, and must be “made conscious” if we are to grow spiritually, Nicoll advises.

Nicoll writes of the “negative background” people have in their psychology—for example, the “self-pity” and “sense of grievance” people “lie on as on a bed in the background” of themselves. This “great background of internal considering” only makes people bitter; we constantly “think that life should treat us better … that people should treat us better.” “An over-sensitive reaction to the ordinary events of life can charge us up with negative emotions which come through this self-pitying view of life that we take,” he explains, and in this way “we accumulate a lot of internal accounts every day and build up a dragging past, a sick past” in our psyche.[154]

“If a person is not increasing … consciousness by observing himself, he will be unaware that after a time he is filled up with plenty of materials for some [emotional] explosion.” Nicoll writes. “An explosion of negative emotions is the result of making, half-consciously, [these] inner accounts over some time. It is not the apparent immediate irritation that causes them. That merely fires off the accumulation of them.” This accumulation can happen, “in a very silent, subtle way” as negative emotions can “take many subtle forms.” “We indulge so frequently in negative emotions, obvious or less obvious, cruder or subtler, open or concealed.” “If we do not observe this” happening , he writes, then our “constant unconscious way of taking everything … can become so exaggerated that everything, all day long, upsets us and makes us feel miserable.” Furthermore, this ongoing process of “account making” cripples you inside, even if hidden behind a smile: “You smile—bravely—you all know that brave smile—and it is all lies.”[155]

…we need to observe and separate from “all sorts of subtle depressions apart from … obvious negative emotions.”

This unconscious background of negativeness obstructs finer influences from reaching us, and must be “made conscious” if we are to grow spiritually, Nicoll advises. We should aim, therefore, “not to feel always this background of tears, discontent, of being not appreciated,” and use self-observation to “penetrate more deeply into the background” which lies in the “dark, unconscious side of ourselves” and become conscious of it. “There is always something to work on but you do not observe it,” he points out, because you only “look for big things, for crises, not little daily things.” However, we need to look at our “slight but negative” feelings because “big things begin from little things.” Thus we need to observe and separate from “all sorts of subtle depressions apart from the more obvious negative emotions.”[156]

Tolle

Tolle also describes “background unhappiness” that people have in their psyche. He writes, for example, of “the background static of perpetual discontent” and “background resentment” and unhappiness people carry, consisting of “subtle forms of negativity” that is many people’s “normal” or “predominant inner state”. This “almost continuous low-level” negativity is the “background ‘static’ of ordinary unconsciousness.” This “ordinary unconsciousness” is habitual, and creates an undercurrent of “unease and discontent that most people accept as normal living.”[157]

You should … “monitor your mental-emotional state through self-observation” … to detect any “low-level of unease, the background static” and “make it conscious,” Tolle advises.

But there is a mechanism by which “ordinary unconsciousness turns into the pain of deep unconsciousness.” If the past takes up “a great deal of your attention,” through frequently thinking about “your victim story,” and feeling emotions like “resentment, anger, regret, or self-pity,” then there will be “an accumulation of past in your psyche.” This underlying past emotional pain can then be “intensified through some challenge or threat to the ego” which “brings up intense negativity such as anger, acute fear, aggression, depression,” Tolle explains. This “often means that the pain-body has been triggered,” in which case “even a minor situation may produce intense negativity, such as anger, depression, or deep grief.” “In many cases, happiness is a role people play, and behind the smiling façade, there is a great deal of pain,” he writes. “Depression, breakdowns, and overreactions are common when unhappiness is covered up behind a smiling exterior.”[158]

You should therefore “monitor your mental-emotional state through self-observation” in order to detect any “low-level of unease, the background static” and “make it conscious,” Tolle advises. We need to “break the habit of accumulating and perpetuating old emotion” and refrain from “mentally dwelling on the past.” By observing and dealing with the “ordinary unconsciousness” and discontent which is commonplace, “it will be much easier to deal with deep unconsciousness” when it arises.[159]

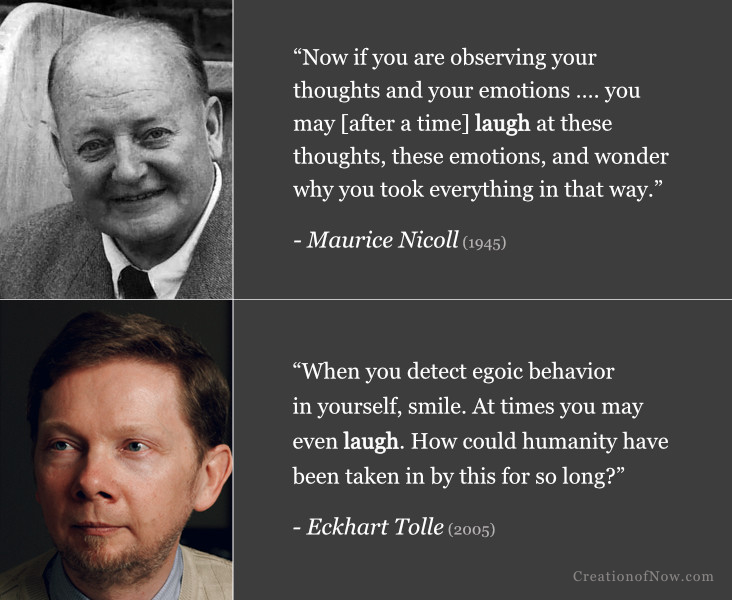

Laughing at oneself

We’ve been exploring different dimensions of the shift in perspective brought about by practicing self-observation, as described by Nicoll and Tolle. There is another quality emerging from this worth mentioning—the capacity to laugh at oneself.

To be more specific, the authors describe how you gain the ability to laugh at the unconscious states you observe in yourself, which formally you may have strongly identified with and were heavily invested in or weighed down by.

Being able to laugh at yourself—at your habitual thoughts and emotions, and the “false self” that often underpins them[160]—is a positive sign, they say. This may occur as we bring these attributes into the light of consciousness which reveals their pointlessness to us. Generally speaking, the capacity for self-humour may be a side-effect of breaking identification with what you observe—no longer taking it as who you are and seeing its futility or ridiculousness.

Both describe the light of consciousness increasing through this process while, likewise, any unconscious attributes observed within are said to diminish or dissolve (an idea I’ve discussed at length previously).

It is a good sign when you can laugh at what you observe in yourself, Nicoll and Tolle convey. However, Nicoll is clear this laughter is directed only at oneself, whereas Tolle suggests the laughter may be directed at “humanity.”

Nicoll writes for example: “there is a certain inner laughter about oneself that is extremely useful in this Work”. “If you are observing your thoughts and your emotions” you can reach a point where “you may laugh at these thoughts, these emotions, and wonder why you took everything in that way.” By “seeing what you are not,” through self-observation, you can “get away from this great fiction that you have kept up,” which consists of everything “belonging to the False Personality.” But this must be done “with a certain amount of humour, with a certain capacity for real laughter at yourself.” When, via self-observation, “the light of consciousness” meets “what was operating unconsciously” it “illumines” its “ridiculousness,” and “consciousness increases at its expense.” One is then “able to laugh at” their “self-love” (i.e. conceit) more and more as “one loses the former highly-explosive over-sensitive feeling of ‘I’” as it is “diminished”.[161]

Tolle similarly writes that when observing oneself, one can smile or laugh at their thoughts and ego. “Some people laugh out loud” when they “see the dysfunction” in their “thoughts and actions”. “When you observe the ego in yourself, you are beginning to go beyond it,” he writes, but you should not “take the ego too seriously” when you observe it but “smile” at it: “When you detect egoic behavior in yourself, smile. At times you may even laugh. How could humanity have been taken in by this for so long?” This sense of humour arises when your “sense of self” is no longer derived from thoughts or the ego, he explains: “One day you may catch yourself smiling at the voice in your head, as you would smile at the antics of a child. This means that you no longer take the content of your mind all that seriously, as your sense of self does not depend on it.” As this occurs “the light of your consciousness grows stronger” he suggests, while the dysfunction observed “begins to dissolve”.[162]

Seeing what you are not

Of course, in the examples above, they are not talking about laughing at our real self, but our false self and the associated mental-emotional attributes we mistake for who we are.

On a somewhat related point, they also suggest that it’s by seeing and recognising what you are not that you recognise who you really are.

“You cannot tell yet what you are save by seeing what you are not,” writes Nicoll, and it is the gradual separation from the fiction of “the False Personality,” that allows one to find something “deeper and more genuine.” [163] Similarly, “the recognition of illusion is also its ending,” writes Tolle. “In the seeing of who you are not, the reality of who you are emerges by itself.”[164]

You discover who you are by seeing, and ceasing to identify with, the fictitious illusion you are not, Nicoll and Tolle say.

This is perhaps the most important aspect underlying the overall inner shift to outer life we’ve been discussing: Self-observation can bring us to consciousness and real being. By taking life and its events consciously through self-observation, what is real in us must come forward to meet the moment—in place of those unconscious factors that otherwise govern our reactions, and which now can be seen as not us.

I’ll end this segment with a final quote from Nicoll that encapsulates the idea.

Closing Comments

Self-observation is essentially an exercise to adopt a more aware state of consciousness and watch the inner factors that, ordinarily, compel us to live through unconscious reactions and states.

I’ve examined how Nicoll and Tolle correspond on this before, particularly with respect to identification with inner states. In this piece, I’ve come from a slightly different angle, highlighting a particular theme and approach the authors often emphasise: utilising self-observation to change one’s inner perspective or attitude toward outer life.

Both authors point out that the distinction between life’s events and our psychological reactions towards them is not often clear to us. So entrenched is our identification, they say, that we take the two as the same, our reactions as inevitable—or at least justified.

They emphasise observing one’s inner world or reality and learning to make a conscious distinction between events and our habitual reactions to them. In this way we can start to transform our lives, we are told. But we must be willing to take responsibility for our inner state irrespective of outer circumstances and address our negative states especially. Only by living more consciously in this way, they suggest, may we come to experience an inner peace and inner freedom that’s independent of external events.

It’s remarkable to me just how much the authors correlate in the ways they write about these ideas. Nicoll was of course a Fourth Way teacher; he presented his most extensive material as “commentaries” on the work of his predecessors, Gurdjieff and Ouspensky, yet greatly elaborated on the psychological side of the teaching in the process.

Nicoll’s obscurity contrasts starkly with Tolle’s celebrity however. Tolle is not only a bestselling author, but perhaps the most popular contemporary spiritual teacher in the western world outside of organised religion. Nicoll, however, is largely unknown outside of esoteric circles.

Some then might be surprised at just how many concepts in Tolle’s bestselling work find strong precedence in comparatively obscure esoteric texts of the mid-20th century, given Tolle provides no indication of having ever studied the Fourth Way in his books. The similarities are most striking, I have argued, with the practice of self-observation that Nicoll and Tolle both deem so essential. There are a number of more peripheral terms, ideas or expressions that correspond across their work too. Many of Tolle’s core ideas, it seems, are not as original as some might think; what seems more unique is the way he appears to have adapted and popularised them for mainstream audiences.

I hope that this third instalment in my self-observation series, in combination with my previous material, can shed further light on this interesting and significant cultural phenomenon. Nicoll may be largely forgotten, but his influence is still with us today. This influence is surely a culturally—and perhaps spiritually—significant occurrence worth recognising and understanding, whatever we may think of the authors concerned.

There are more commonalities between Nicoll and Tolle to discuss however, and I’ll explore this matter further going forward.

A.Basedow

Dear Jack, I appreciate and thank you for the immense effort you invested in bringing together these quotations to show Tolle’s unacknowledged use of Nicoll’s Commentaries. It’s really shocking.

Without doing any justice to the comprehensiveness of Nicoll’s work I’ve got a few remarks about its difference from Tolle’s books and talks.

The comparisons can give someone who has never heard of Nicoll the impression that he and Tolle are very similar, birds of a feather, whereas they are not.

Nicoll, besides being a psychiatrist and neurologist, was a teacher of the Fourth Way or Work, initiated by Gurdieff and Ouspensky. Explanations of Nicoll’s teaching deduced from insights which Tolle took over and reformulated not only stress the similarities but they may even give Tolle a certain time tested value. By just relying on the comparisons you could conclude that Nicoll and the Fourth Way teachings are as easy to understand as Tolle’s. That is not the case.

The commentaries were written for Nicoll’s pupils whose individual advance in the Work he knew well. They explain ideas but are above all requests and demands to work on certain aspects which were still neglected. He said that the teaching can only be oral and that the Commentaries are not the Work. The Work has to live in the hearts of men and women. It has to renew itself and reveal ever new aspects.

Behind every quotation from Nicoll hide far reaching Fourth Way ideas which one has to know and understand to be able to practice. The aim you have doing the Work depends on them. Self-observation and non-identifying are not an aim in itself. They are a means to purify the psyche to be able to be reached by higher levels.

The Fourth Way teachings are precise. The many 4th Way diagrams of the transformation of energies and of what precisely goes on inside you, like the enneagram, the different cosmic laws which act on us, the centres of thinking and feeling and their subdivisions are difficult to fathom. You have to learn the 4th way ideas like you learn any other skill, you have to understand them and apply them, verify their accuracy by experience. It costs effort and it takes a long time to make any progress.

If you have to know or do something precisely it makes you feel uncomfortable. Not knowing, not doing the practices as they are meant to be done and not doing them enough makes you feel uncomfortable. Uncomfortable as well is the fact that higher centres which are working in you cannot reach you because you are not attuned to them owing to being obsessed by all your wrong and unnecessary psychological functions described in the articles.

The 4th way terminology is unruly: ‘External/internal considering’, ‘chief feature’, ‘making accounts’, ‘self-remembering’, ‘conscious shock’, ‘inner taste’ and more. Once again you have to make an effort to extract the meaning, understand and observe/practice and make it your own.

Tolle uses ‘grievance’ as an equivalent of ‘internal considering’. Sure one knows what a grievance is. ’Internal considering’ concerns much more than a grievance.

Tolle’s accommodation of Nicoll’s insights into every day language gives the illusion of quick and once and for all knowledge and understanding. This feels comfortable and can be tranquillising.

If Nicoll and Tolle say almost the same, why become interested in Nicoll?

Someone who appreciates the inner and cosmic hierarchies of the Fourth Way is not left to his own devices what concerns the direction the development of his consciousness is to take beyond an initial stage.

‘We have no Self – Knowledge only imaginary Self – Knowledge. Self -Observation without direction is quite sterile, but once we begin to observe ourselves from the angle of the Work we get direction’ Maurice Nicoll, ‘Informal Work Talks and Teachings’, Quacks Books York,1995, p. 90

Kind regards,

A.Basedow

Jack Dawes

Thank you for your comment and appreciation A.Basedow.

While I’ve mainly focused on highlighting similarities between Nicoll and Tolle, to show the influence Nicoll has likely had, I do agree they have big differences too.

One of the main differences I noticed, which I’ve commented on here in some places, is how Nicoll stresses that the process of awakening is difficult, while Tolle suggests it can be easy (see the discussion here for example). Tolle even expresses hope that “the word work” might die out in one place. It would be difficult to imagine Nicoll, or any teacher of The Work, saying that!

You highlight many more multifaceted differences between them in your comment, which really brings home the point that these two are certainly not birds of a feather, despite the similarities that do appear in their works.