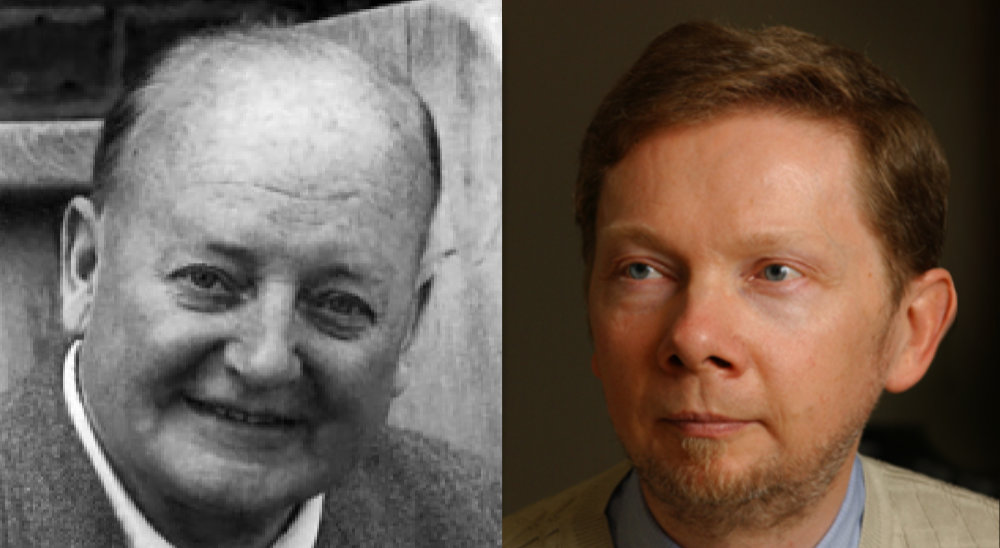

Eckhart Tolle mirrors Maurice Nicoll in making “the light of consciousness” integral to the practice of self-observation and inner spiritual change.

I am continuing to compare similar statements made by bestselling contemporary author Eckhart Tolle and Fourth way teacher Maurice Nicoll—whose works on esoteric psychology were published mid last century.

I’ve written extensive comparative analyses on these authors’ works. This post is the second in a series where I summarise the main similarities I’ve found by topic. Part one was on the practice of self observation. This second part is on a theme Nicoll and Tolle connect closely with that practice: “the light of consciousness.” I explored this concept in depth in an earlier article; in the tables below I outline the key textual similarities I discovered.

In Nicoll’s writing, perspectives from two psychological systems— Carl Jung’s analytical psychology and G.I. Gurdjieff’s Fourth Way—sometimes converge. This can be seen when he describes “the light of consciousness” and the dark side of our psyche. From Jung comes an emphasis on making the dark unconscious side of us conscious, and the notion we project our unconscious attributes onto others. From Gurdjieff and P.D. Ouspensky comes the primary method to study our unconscious reactions and states and become “more conscious”: self-observation.

It’s primarily through self-observation, Nicoll maintains, that we bring our dark, unconscious aspects into the light of consciousness. This lets a “ray of light” of consciousness into our psyche, revealing unconscious thoughts, emotions and impulses as they occur and making inner change possible. Nicoll puts great emphasis on this idea, using variations of the phrase “light of consciousness” more than 50 times in his writing.

Eckhart Tolle noticeably mirrors Nicoll on this theme, both conceptually and descriptively. He writes, for example, of a “beam of light” being directed within via observation. Both authors tell us anything unconscious or “unobserved” must be brought “into the light of consciousness” by direct observation to “make it conscious.” Only then will it lose “power over you” and diminish—while consciousness, meanwhile, can grow or increase. They similarly describe how we “project” our unconscious attributes onto others as well.

As previously, the tables below present similar statements by each author side-by-side for comparison. Quoted text is bolded or underlined in places to emphasise key commonalities, but italics are original to the source material.

Into the light of consciousness

| Maurice Nicoll | Eckhart Tolle |

| ‘By true self-observation we let a ray of light into ourselves. . . . Not . . . physical light but the light of Consciousness.’[1] | ‘Just observe the emotion. . . . Attention is like a beam of light – the focused power of your consciousness.’[2] |

| ‘By the method of self-observation . . . [we] bring this not yet known side of ourselves into the light of consciousness.’[3] | ‘You are the watcher, the observing presence. If you practice this, all that is unconscious in you will be brought into the light of consciousness.’[4] |

| ‘The dark side of ourselves . . . we do not see, are not aware of, and so do not acknowledge. . . . Yet this side acts all the time—and the tragedy is we do not see it.’[5] | ‘Ego is the unobserved mind that runs your life when you are not present as the witnessing consciousness, the watcher.’[6] |

| ‘Make your dark, unobserved side more conscious to you . . . this dark—i.e. unconscious—side of yourself, the side that you do not know about yet, the side you have not yet observed.’[7] | ‘The pain-body, which is the dark shadow cast by the ego, is actually afraid of the light of your consciousness. . . . Its survival depends on your unconscious identification with it.’[8] |

| ‘Self-observation is to let the light of consciousness into what lies in darkness within us. . . . Consciousness . . . is light.’[9] | Observe it. . . . As you do so, you are bringing a light into this darkness. This is the flame of your consciousness.[10] |

Making it Conscious

| ‘This dark side . . . we must penetrate and make it increasingly conscious to ourselves by self-observation. . . . We have to make it conscious but not take it as ourselves.’[11] | ‘Observe the peculiar pleasure you derive from being unhappy. Observe the compulsion to talk or think about it. The resistance will cease if you make it conscious.’[12] |

| ‘Get to work and make it conscious by means of candid self-observation.’[13] | ‘Make it conscious. Observe the many ways in which unease, discontent, and tension arise within you.’[14] |

| ‘Suppose a person’s . . . habitual psychological activity consists . . . in blaming . . . in violence, in feeling upset by every life-event, in being negative and so on. . . . How then to get out of it? First, by observing . . . and acknowledging it.’[15] | ‘Observe the attachment to your views and opinions. Feel the mental-emotional energy behind your need to be right and make the other person wrong. . . . You make it conscious by acknowledging it.’[16] |

The light of consciousness brings change

| Maurice Nicoll | Eckhart Tolle |

| ‘A mechanical reaction . . . will regularly recur unless you put the light of consciousness into it. It is consciousness that changes us. First the effort of self-observation is needed.’[22] | ‘The tiniest negative emotion . . . can . . . serve as a doorway through which the pain-body can return. . . . The pain-body needs your unconsciousness. It cannot tolerate the light of Presence.’[23] |

| ‘We are living in a state of internal darkness, and nothing can be changed unless we let light into this darkness. . . . Self-Observation, by letting in light, begins the change in us.’[24] | ‘Observe the attachment to your pain. . . . You can then take your attention into the pain-body, stay present as the witness, and so initiate its transmutation.’[25] |

| ‘Self-observation is like a ray of light that penetrates the darkness inside us. The result of this ray of light is to bring into consciousness the unknown and unaccepted sides of ourselves.’[26] | ‘Through sustained attention and thus acceptance, there comes transmutation. The pain-body becomes transformed into radiant consciousness.’[27] |

| ‘Nothing can change in us unless it is brought into the light of self-observation, that is, into the light of consciousness.’[28] | ‘If you don’t bring the light of your consciousness into the [emotional] pain, you will be forced to relive it again and again.’[29] |

| ‘Remember, a thing in you cannot change if it remains unconscious to you. . . . If you cannot observe a thing in yourself you cannot change it.’[30] | ‘Bring the feeling of it into awareness as much as possible. Attention is the key to transformation—and full attention also implies acceptance.’[31] |

| ‘Inner attention increases our consciousness of inner objects. . . . If you observe a thought or a feeling . . . you will realize that it is something in you, but not you. When you do not . . . everything lies in darkness. . . . It is therefore a good thing to let a ray of light in. This is self-observation.’[32] | ‘Whatever it is, catch it before it can take over your thinking or behavior. This simply means putting the spotlight of your attention on it. . . . Any emotion that you take your presence into will quickly subside and become transmuted.’[33] |

| ‘When you become conscious of something that you constantly say or feel or think . . . it begins to be ‘not I’. . . . You rise a little in your level of being through . . . the light of consciousness.’[34] | ‘By making this pattern conscious, by witnessing it, you disidentify from it. In the light of your consciousness, the unconscious pattern will then quickly dissolve.’[35] |

| ‘It is the light of consciousness that begins to change things [in you].’[36] | ‘Inner factors such as fear … will dissolve in the light of your conscious presence.’[37] |

| ‘The remedy is the light of consciousness’[38] | ‘The light of consciousness is all that is necessary.’[39] |

Disempowering unconsciousness, increasing light

| Maurice Nicoll | Eckhart Tolle |

| ‘Whatever we bring into the light of consciousness loses the power it has over us if it remains unconscious.’[43] | ‘Anything unconscious dissolves when you shine the light of consciousness on it.’[44] |

| ‘The more unconscious a thing, the more power it exerts. . . . To bring a thing up into the light of Consciousness is to rob it of its power.’[45] | ‘I had . . . witnessed a diminishment of the pain-body . . . through bringing the light of consciousness to it.’[46] |

| Observed mechanical traits ‘lose their power over you.’ [47] | A witnessed thought ‘loses its power over you.’[48] |

| ‘To make an [unconscious] attitude conscious is to deprive it of its power over you.’[49] | ‘The unconscious resistance is made conscious, and that is the end of it.’[50] |

| ‘We are gradually freed, gradually made less and less under its power . . . through the increase of consciousness . . . [which] renders mechanical behaviour less dominating.’[51] | ‘It is a silent but intense presence that dissolves the unconscious patterns of the mind. They may still remain active for a while, but they won’t run your life anymore.’[52] |

| ‘Now the object . . . is to let a ray of light into the inner darkness of ourselves. . . . Seeing . . . a part of the darkness and bringing it into consciousness . . . is an extension of consciousness—an increase of consciousness.’[53] | ‘Bring more consciousness into your life in ordinary situations. . . . In this way, you grow in presence power. . . . No unconsciousness, no negativity . . . can enter that . . . and survive, just as darkness cannot survive in the presence of light.’[54] |

| ‘One must, to begin with, sacrifice one’s [psychological] suffering. All self-pity, all self-cradling . . . all pitiful pictures, all sighs, inner groans, and complaints, must be burned up in the fire of increasing Consciousness.’[55] | ‘Sustained conscious attention . . . brings about the process of [psychological] transmutation. It is as if the [emotional] pain becomes fuel for the flame of your consciousness, which then burns more brightly as a result.’[56] |

| ‘Consciousness is light. An increase of consciousness illuminates more and more.’[57] | ‘The light of your presence will shine brightly, and it will [then] be much easier to deal with deep unconsciousness.’[58] |

Projecting unconsciousness onto others

| Maurice Nicoll | Eckhart Tolle |

| ‘People project [their] unaccepted psychology on to others.’[59] | ‘[You] project your own unconsciousness onto another person.’[60] |

| ‘They are unconscious of their own psychology. The consequence is that they see what is in them projected outside them like a magic-lantern slide on to another person.’[61] | ‘Who is doing that? The unconsciousness in you, the ego. Sometimes the “fault” that you perceive in another isn’t even there. It is a total misinterpretation, a projection.’[62] |

| ‘The faults we dislike most in others are usually those that we display ourselves without being conscious of them.’[63] | ‘The particular egoic patterns that you react to most strongly in others . . . tend to be the same . . . that are also in you, but that you are unable or unwilling to detect.’[64] |

| ‘We project this side of ourselves and see it in other people. For example, we see them as liars, or unfaithful, or mean, or untrustworthy, and so on, in relation to our own qualities.’[65] | ‘You have much to learn from your enemies. What is it in them that you find most upsetting . . . ? Their selfishness? Their greed . . . insincerity, dishonesty . . . or whatever it may be?’[66] |

| ‘Everything that you are so critical of in others is expressing itself in you.’[67] | ‘Anything that you resent and strongly react to in another is also in you.’[68] |

| ‘Because he does not see it in himself, he is over-critical of it in others.’[69] | ‘What you react to in another, you strengthen in yourself.’[70] |

| ‘We have . . . to become far more conscious to ourselves. . . . The thing you criticize so much in other people is . . . lying in the dark side of yourself. You only see this . . . unconscious, unknown side of yourself, reflected into other people.’[71] | ‘Very unconscious people experience their own ego through its reflection in others. When you realize that what you react to in others is also in you (and sometimes only in you), you begin to become aware of your own ego.’[72] |

| ‘When we are up against someone else . . . that is the very thing we have to work on in ourselves. . . . Everyone lives in . . . a very petty world of self-reactions. . . . But when the light of self-observation is thrown into this dark side, consciousness . . . increases.’[73] | ‘It’s more important to observe it in yourself than in someone else. . . . The pain-body will create a situation in your life that reflects back its own energy. . . . [It] is the dark shadow cast by the ego . . . afraid of the light of your consciousness.’[74] |

Concluding Comments

When we compare Maurice Nicoll and Eckhart Tolle on theme of “the light of consciousness,” we can see there is a strong correspondence between them. I’ve analysed these commonalities before in a more extensive article which provides greater background and context. In this article I’ve summarised the similarities I discovered and made them easier to compare.

Both authors repeat the phrase “light of consciousness” multiple times and use similar variations: Nicoll refers to “the light of self-observation” for example, and Tolle refers to “the light of Presence.” But it has the same meaning in whatever form.

For these authors, the light of consciousness is active in the present-moment act of self-observation itself, and it’s through this practice that we bring an unconscious attribute “into the of light consciousness” and “make it conscious.” It’s by correct inner observation that we both see an unconscious aspect that’s active in us and, importantly, break identification with it. This allows the light of consciousness to bring about inner change by disempowering what we’ve observed—so that it loses “power over us.” There’s also reference to the light of consciousness being a flame or fire, and of aspects of our inner darkness being consumed in it by this method, with the light of consciousness growing stronger.

There’s a close correspondence between Nicoll and Tolle on the idea we project our unconscious attributes onto others too. The things we dislike most in others tend to exist in us unseen and unacknowledged, they say. Both propose self-observation as the solution, suggesting we try to see in ourselves the flaws we notice and dislike in others.

It is interesting to consider some of the history behind these concepts. Both Gurdjieff and Jung—who operated in the early 20th century quite independently of one another it seems—had discussed the “light of consciousness” and the need to become conscious of psychic processes operating unconsciously in us. Both had pointed out that the flaws we see in others tend to exist unrecognised in us too. Each taught psychological systems which embraced more esoteric or spiritual outlooks.

Nicoll was uniquely placed as a student of both systems, and seamlessly drew from either when he taught the Fourth Way. Ultimately he gave precedence to the Fourth Way, favouring its self-observation method for self-knowledge and inner change, but the evocative language he used when he discussed these themes—such as presenting the process as an inner struggle between light and darkness—owes a good deal to Jung’s influence as well.

But mostly, Nicoll’s approach here stands out due to his inspired ability to combine his understanding of different teachings with his own insights into the human psyche, and communicate fundamental principles in vivid, compelling prose. It’s worth considering just how unique his work was at the time he was writing.[84]

Given Nicoll’s relative obscurity, it is interesting to see his unique approach, and the typical expressions he used, being mirrored today in the works of contemporary figures like Eckhart Tolle—a bestselling author many regard as the most popular independent spiritual teacher in the world.[85]

Nicoll may be largely unknown today, but his influence is pervasive.

I’ll continue presenting a summary of the similarities I’ve discovered in the works of Maurice Nicoll and Eckhart Tolle in my next post.

Leave a Reply