Maurice Nicoll (1884-1953) was a British physician, psychiatrist, writer and WW1 veteran. A close friend and protégé of Carl Jung, he later studied with prominent esotericists Gurdjieff and Ouspensky, and was, in his last decades, a teacher and author of the Fourth Way system they imparted. This is the first of many blogs I intend to write on Nicoll, whose work I believe carries more significance and influence than is commonly recognised, despite his relative obscurity. Here I give some general background on his life, and hopefully a sense of why his work warrants more attention.

Maurice Nicoll (far right) with Gurdjieff (far left) in Paris in 1922. Nicoll’s wife and Madame Ouspensky sit between.

Maurice Nicoll once had a dream, described in his writings on esoteric psychology. Someone pushes him up a grassy slope, but his progress is blocked at the top by a “difficult-to-cross ditch.” It was not very wide but extremely deep, filled with “the bones of prehistoric animals—the remains of violent things, of beasts of prey, of monsters, of snakes” stretching “far down into this abyss.”[1]

Restrained by fear and some invisible powerful force, he is frozen in place and cannot cross. But then, suddenly, he is on the other side, and given “a glance” of the land beyond. It is a place for people with a different “state of will”.[2] This is shown by a man he encounters teaching new recruits:

At first sight there seems nothing marvellous. He smiles. He indicates somehow that he does not necessarily expect to get any results from what he is doing. He does not seem to mind. He does not shew any signs of impatience when they are rude to him. The lesson is nearly over, but this will not make any difference to him. It is as if he said, “Well, this has to be done. One cannot expect much. One must give them help, though they don’t want it.” It is his invulnerability that strikes me. He is not hurt or angered by their sneers or lack of discipline. He has some curious power but hardly uses it. I pass on, marvelling that he could do it. I could not take on such a thankless task.[3]

Journeying further, Nicoll comes to a storehouse of boats, beyond which is the sea. On waking, he wondered about that man, reckoning he was bound to sail off in one of the boats once his task was done. Reflecting further, he realised what made him so different: He was “purified of all violence”. That was his secret and the source of his power. Nicoll meant something more than the absence of physical violence, but the eradication of all psychological violence engendered by negative emotions, which he identifies as the root of all violent action.[4]

Nicoll seemed to recognise that this man represented someone who inhabited a “psychological country”—a term he came to use in his writing—that was “utterly contrary” to his own. “I would have reacted violently to those recruits,” he admits. And he understood that to reach to the inner state the man possessed he would have to somehow, within himself, permanently cross the “deep gulf full of the bones of prehistoric beasts” that still separated him from “the country of the non-violent.”[5]

Nicoll realised he hadn’t “really crossed that deep gulf yet.” “In this dream,” he explains, “I was shewn quite simply a direction and state of will that at the time seemed impossible for me to follow or ever reach.” But this vision, though only a glance, let him see that it was possible, and impressed upon him a “new direction” to aim for in life—one which would require “a new will purified from violence.” “I know also,” he wrote, “that the possibilities of following this new will and new direction lie in every moment of one’s life—and that I continually forget.”[6]

The importance of this dream to Nicoll is underscored by the fact he relates it three times in his work. He first shares it in 1951, but mentions it happened “some time ago” before recounting it.[7] From his description, I gained the impression it occurred before he taught the esoteric system he learned from Gurdjieff and Ouspensky, since, in his account, he reflected upon waking that “there were no recruits for me.” [8] And there were none before 1931 in any case.

But from 1931, Nicoll did have “recruits” of his own, having been requested by Ouspensky to “go away, and teach the system,” which he did until his death in 1953.[9] He oversaw his own groups and pupils from then on, whereas earlier he had studied under Ouspensky or Gurdjieff. However his secretary and biographer Beryl Pogson indicates this dream did occur in 1951. But whatever the timing, one gets a strong sense from reading Nicoll’s work that he did in some way strive in the general direction it illustrated throughout his teaching career, and continued these efforts to the end of his life.[10] In the process, he left behind a trove of written material, including weekly lectures delivered to his groups between 1941 and 1953, published as Psychological Commentaries on the Teaching of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky, which exert a wide-ranging undercurrent of influence, extending beyond the Fourth Way. Yet he nevertheless remains a relatively obscure figure today.

If you have never heard of Maurice Nicoll—as I admit I hadn’t until relatively recently—you might be wondering just who he is and why I’m writing about him at all. And if, like me, you have never had any direct association with the Fourth Way system he taught, that would be quite understandable. Nevertheless, if you have an interest in spirituality, particularly in how certain ancient or timeless ideas have found expression—for better or worse—in modern spirituality in the West, you might be surprised, as I was, at how familiar Nicoll’s work seems to be—at how ideas and expressions that have since suffused this field find a certain precedence in his words. I believe his work was in some ways a forerunner for things to come.

Just how that is so will hopefully become clearer the more I write at this blog, but I intend to give some indication in this first post. Some substantive biographies have been written on Nicoll already, and I don’t want to reinvent the wheel, but for context I’ll cover some key facts about his life before circling back to briefly address this idea.

Early Life and Career

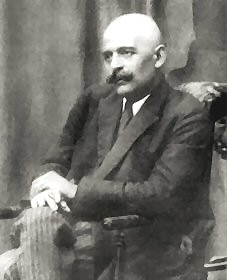

Maurice Nicoll was the son of a Scottish Free Church Presbyterian Minister—the author, editor and theologian Sir William Robertson Nicoll. Illness forced the elder Nicoll from the ministry into a literary career when Maurice was very young. As a noted writer and editor of influential newspapers and magazines, some of which he founded, Sir Nicoll gained considerable literary influence in his day, and was even described as “the most successful Christian of Modern times” by one of his contemporaries.[11] He was a self-made man who grew up in poverty, losing his mother and three siblings to tuberculosis, but his personal success meant that Maurice Nicoll was born into a wealthy family.[12]

William Robertson Nicoll in 1895. He was knighted in 1909 for his literary contributions.

The younger Nicoll shared his Father’s talent for writing, but also had aptitudes for music, painting, science and mechanics. And quite unlike his Father, from a young age he came to loathe conventional Christianity, at least in the form it had been taught to him. He did not reject spirituality outright though, and in fact he was strongly drawn to it, but felt he could not find the answers he sought through a conventional religious education, which he found to be a gloomy, boring affair. In his childhood it seemed to Nicoll that, “sin and the feeling of being a sinner was the main idea of religion. I never understood anything else in regard to religion as a boy and so was either afraid or worried or hated the whole thing. I began to stammer badly.”[13] Nicoll goes on to relate an experience in Sunday school that was a turning point in his understanding:

I listened to the scriptures, mostly drawn from the Old Testament, which always seemed indescribably horrible. God was a violent, jealous, evil, accusing person, and so on. When I heard the New Testament I could not understand what the parables meant, and no one seemed to know or care what they meant. But once, in the Greek New Testament class on Sundays, taken by the Head Master, I dared to ask, in spite of my stammering, what some parable meant. The answer was so confused that I actually experienced my first moment of consciousness—that is, I suddenly realized that no one knew anything. . . . From that moment I began to think for myself or rather knew that I could…. I remember so clearly this class-room room, the high windows constructed so that we could not see out of them, the desks, the platform on which the Head Master sat, his scholarly, thin face, his nervous habits of twitching his mouth and jerking his hands— and suddenly this inner revelation of knowing that he knew nothing—nothing, that is, about anything that really mattered. This was my first liberation from the power of external life. From that time, I knew for certain—and that means always by inner individual authentic perception which is the only source of real knowledge—that all my loathing of religion as it was taught me was right.[14]

Emphasis must be laid on the words “as it was taught me.” For despite this sentiment, from his early childhood Nicoll felt and preserved “a dedicated affection for the being of Christ” that was distinct from any religious dogma.[15] Later in life, Nicoll drew a clear distinction between the teachings and parables of Jesus, which he treasured as a source of “esoteric psychology” concerned with inner transformation,[16] and the external religiosity of conventional Christian observance.[17] But before reaching that understanding, Nicoll as a young man sought out higher meaning beyond the Christian sphere, studying the literature of metaphysical philosophy, esotericism and mysticism. But it was when he began a career in psychiatry, by which he became a close friend and protégé of Carl Jung, that he first ventured into the psychological realm as a pathway to self-development. However, much like Jung himself, before his search for higher meaning via the psyche got underway, Nicoll first studied material science.

Nicoll majored in science at Cambridge University and qualified as a medical Doctor at St Bartholomew’s Hospital in 1910. He then worked as a general practitioner—but this vocation left him unsatisfied.

Nicoll began pursuing a literary career on the side, writing serial stories under the pen name Martin Swayne. These were published in The Strand magazine and later released as novels. It began with the comedy Lord Richard in the Pantry, which was started with his sister as a light-hearted diversion—apparently to help cheer her up as she recovered from an illness. But the humorous tale of a broke aristocrat becoming a household butler was a hit: it became a successful book and was adapted into a long-running West End play and later a film. Other stories soon followed.

Meeting Carl Jung and the Outbreak of War

But Nicoll’s real interest then lay in the emerging field of psychology, which at that time was still struggling to gain acceptance in the mainstream medical community. He split his time between practicing medicine and studying psychology, and spent a year abroad in 1912 to study this new discipline in Paris, Berlin, Vienna—where he learned the system of Freud—and finally Zurich, where he worked directly with Jung and the two became close friends. It was the first of a number of visits.

Meeting Jung was another turning point in Nicoll’s life; he describes Jung as his “first psychological teacher”[18] and he clearly had a profound impact on his life. Jung did not instigate Nicoll’s yearning, and search, for deeper meaning, but he provided a new avenue to pursue it within the medical profession—an approach for which Jung was a trailblazer.

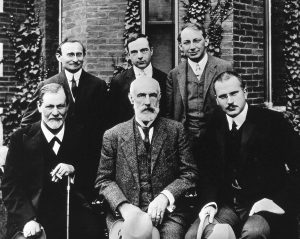

Carl Jung (bottom right) with Sigmund Freud (bottom left) and other early psychologists in 1909.

Jung famously broke with the founder of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud, in 1913, although their relationship was already strained in 1912 when Nicoll first met Jung. Freud disapproved of the new quasi-religious directions Jung was taking. Jung was convinced that dreams were not only an outlet for the expression of repressed desires, but could offer intelligent symbolic insights into an individual’s potential for psychological development—an underlying process Jung believed to be universal, and would eventually term individuation. Jung’s perspective on dreams clearly resonated with Nicoll until the end of life. In 1952 he commented on Jung’s break with Freud:

When Jung said to Freud that many dreams had other interpretations than those of retrogressive sexual wish-fulfilments and some shewed useful prospective directions for personal development, he was told that that kind of thing must not be admitted. Jung refused not to admit it. To-day the quarrel with science in general is with its interpretations, some of which are of amazingly poor quality. But many scientists are afraid to say what they think. To declare that there is intelligence behind the Universe means ostracism. [19]

Jung believed the symbolic language found in dreams derived from some shared, inherited ancestral source, and addressed an inner transformational process underlying humanity’s religious and mythic expressions. He observed that universal ideas and symbols—which he came to call archetypes—appeared in the dream content of quite varied people, himself included, in ways that clearly went beyond individual experience. The same also appeared in religious and mythic stories from across the world. Jung proposed these universally appearing archetypes originated from a deeper underlying source—a shared and inherited symbolic storehouse—which he eventually dubbed the collective unconscious.

Jung’s emerging ideas were something Freud, a rationalist, rejected. But this apparent coming together of scientific and spiritual ideas in the framework of Jung’s analytical psychology, and, with it, the prospect of pursuing self-knowledge not just to cure illness but to perhaps find and pursue deeper meaning in life, was very appealing to Nicoll. He would go on to become a leading psychiatrist in London advocating the Jungian method, and published the first English book supportive of Jungian dream analysis, Dream Psychology, in 1917.

But Nicoll’s life, along with all those of his generation in Europe, was violently interrupted by the First World War. He had to urgently cut short his time with Jung in Zurich in 1914 when war broke out, and rush home before travel became impossible.

Nicoll enlisted in 1914 and served as a Captain in the Royal Army Medical Corps, posted to Crete and Mesopotamia where he helped run field hospitals. He was at Gallipoli, Bazra and Amara, at a time when the allies suffered terrible military defeats in the region. Nicoll provided medical care to those who were wounded and ill, in horrendous conditions. He recounts how large numbers suffered and died of heatstroke in the unfamiliar torrid climate, before the knowledge existed of how to properly treat it. His accounts of the war, in fictionalised form, appear in the novel In Mesopotamia, published under his pen name.

Painting of the 1915 Gallipoli landing, from the New Zealand national archives. Nicoll recounts being under fire on the beaches there.

After his active duty ended and he returned to London in late 1916, Nicoll became a leading advocate for recognising and treating “shellshock” (now better understood as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder) as a psychological medical condition, and provided treatment to servicemen in military hospitals whose bodies were whole but were nevertheless clearly unwell—their inner lives having been shattered by the horror of war. Later, he would write of how he and a few others “were fighting for the recognition of the psychological factor in medicine” during “the state of darkness in those first two decades of this [20th] century when the battle for the psychological factor in illness was being waged.” [20]

Becoming a Fourth Way Pupil and Teacher

After Nicoll married in 1920, he and his wife Catherine visited Jung and his wife in Zurich while on their honeymoon. Jung became the Godfather of their daughter the following year. But despite his close personal and professional relationship with Jung, and a flourishing career practicing psychiatry on London’s Harley Street, Nicoll still yearned for something more.

In 1919, while visiting Nicoll in London, Jung shared a dream in which he and Nicoll both laboured at clipping the same tree, but Nicoll worked at a higher level Jung could not understand. Nicoll interpreted this tree to represent psychology—the area they both worked in. Prophetic or not, soon Nicoll would discover and commit to another psychological system he considered more complete than Jung’s. [21]

In 1921, Nicoll wrote down in his journal a “Prayer to Hermes” which expresses an ongoing search for higher meaning. This prayer is directed towards Hermes Trismigistus, the figure at the centre of the Western Esoteric tradition of Hermeticism.

Teach me – instruct me – shew me the Path, so that I may know certainly – help my great ignorance, illumine my darkness? I have asked a question.[22]

A few months later, Nicoll learned that the Russian author and esotericist P.D. Ouspensky had moved to London, having fled the revolution and civil war engulfing his homeland, and was to give lectures. Ouspensky was already fairly well known in England, both for his writing on esoteric topics, which found popularity in Theosophical circles, and for his accounts of the Bolshevik disaster unfolding in Russia. But now he was to talk of something he had not discussed publicly before—an esoteric system he began learning and practicing in 1915 in Russia, under the guidance of G.I. Gurdjieff, an enigmatic Greek-Armenian mystic. Gurdjieff himself, and some of his other early pupils, had also fled Russia, and would eventually settle in France. Ouspensky’s first lecture attracted many people of renown, including “the poet T S. Eliot, Aldous Huxley and his friend the philosopher Gerald Heard, the writer of weird tales Algernon Blackwood, and the occult scholar A.E. Waite, among other notables.” [23]

Ouspensky in 1921

There is much that can and has been written about Gurdjieff and his system, but I’ll just briefly note that Gurdjieff implies he acquired much of his knowledge during years spent travelling though remote parts of Eurasia, where he claims to have attended secretive esoteric schools, carried out archaeological expeditions, and encountered various teachers and fellow seekers.[24] However the exact origins of his system remain shrouded in mystery and the subject of debate. This is inevitable given how difficult it to corroborate the most pertinent details of his travel accounts, which take place in a remote region in a bygone era—other than the likelihood that Gurdjieff, who grew up in Armenia, did travel extensively in the region and period described in his autobiographical book Meetings with Remarkable Men.[25] The sense of mystery surrounding this period of his life is compounded by Gurdjieff’s own penchant for obfuscation and the difficulty one has in separating dramatic allegory—which he had a real flair and liking for—from factual account. As the historian Roger Lipsey notes:

Fact and symbol blend in Meetings and other writings; travel in search is itself the dominant symbol of the book, and we all have unknown landscapes inside. Gurdjieff would sometimes wrap fine meanings in tall tales or run a line of hidden teaching through apparently straightforward story without bothering to signal where fact ends and symbol begins.[26]

Nevertheless, Gurdjieff is recorded telling a pupil “only ten percent is fantasy” in his travel stories,[27] and the detailed descriptions he provided at various times of relatively obscure geographical features and cultural practices of the regions concerned lend some credence to this claim. Whatever the case, what is not beyond debate or doubt is the value Ouspensky, Nicoll and many others saw in Gurdjieff’s system, and the enduring impact it has had since it was first introduced to the West by Ouspensky and Gurdjieff himself.

Gurdjieff in 1922

The main psychological premise of Gurdjieff’s system, which has come to be known as “The Fourth Way” or “The Work,”[28] is that people are asleep—psychologically unconscious—in their so-called “waking” lives. Most of what people “do” is mere mechanical reaction to external events and influences; whether these reactions are in thought, feeling or deed, people have little conscious volition or control over it: everything just “happens”. In place of real consciousness, psychological factors operate in people unrecognised and without their understanding, shaping the life of the individual and humanity as a whole, largely to everyone’s detriment. These inner factors are not fundamentally who people really are, but act through people while they are in this unconscious state.

This lack of consciousness in life and, with it, the resulting lack of knowledge of one’s real inner condition, origin and potential, is pointed to as the chief hurdle to our self-development, and the underlying reason for the world’s bad state of affairs—rife with conflict reaching new and dangerous proportions at the start of the 20th century. Nevertheless, individuals are said to carry an immense latent potential for self-transformation in this teaching. Self-study and inner change—through applying the methods of the work to oneself—are held to set one on a path of inner transformation. Furthermore, it is suggested that if enough people undertook this inner work then mankind’s destructive ways could perhaps be averted or at least decreased—although this system is hardly optimistic about positive mass change occurring, to say the least, and promises no utopia.[29]

Hearing Ouspensky speak and outline this teaching, Nicoll was enlivened. He felt he had finally found what he was looking for. On return from that first lecture that evening, he shook the bed of his sleeping wife—a fellow seeker—to inform her, “This is it.”[30] That she was recuperating from giving birth to their daughter, and that this did not stop Nicoll, a doctor no less, from rousing her, gives a sense of the irrepressible enthusiasm that had taken hold of him. The next evening she began attending Ouspensky’s lectures also, and became just as convinced as her husband.

A few months later, Gurdjieff himself visited London and spoke to the interested people Ouspensky had assembled. Soon after, in 1922, Nicoll and his family moved to Gurdjieff’s newly-formed Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man in France, spending about a year intensively studying under Gurdjieff directly in a community environment. To do so, Nicoll gave up his professional practice in London. This also marked the beginning of the end of Nicoll’s de-facto role as Jung’s protégé and chief advocate in England.

After returning to London in 1923, Nicoll joined Ouspensky’s Fourth Way group there, and soon began working as a psychiatrist again. A close friendship between he and Ouspensky developed; Ouspensky and his wife often stayed with the Nicolls’ on weekends at their country cottage. But in 1931, at Ouspensky’s request, Nicoll began running his own groups, teaching the system independently until his death in 1953.

Ouspensky at the Nicolls’ cottage.

The bulk of Nicoll’s work from that period is recorded in the five volume collection Psychological Commentaries on the Work of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky, which consists of weekly lectures delivered between 1941 and 1953. During that time he also wrote two books illuminating the inner psychological meaning of the Christian Gospels as teachings about self-transformation. These are The New Man and The Mark – the later was not quite completed when he died and was published posthumously. In that period he also published a more abstract and philosophical book on consciousness, time, recurrence and eternity titled Living Time, which he had first drafted while still a pupil of Ouspensky.

The Fourth Way Difference in Modern Western Esotericism

So what attracted Nicoll to this system? For one, compared to anything else he had encountered and studied, he felt The Work was more complete, and formed a well-organised “organic whole.”

[Gurdjieff] said that although several things in this system could be traced in the fragments remaining to us of other systems [of the past], there was no proper organization and arrangement of them [in what remains], and the dependence of one thing on another could not be seen.[31]

You must understand that this system forms an organic whole. To take a small part without connection with the rest is not enough. It is not enough because the meaning of the whole teaching reflects itself into every part of it, and in order to feel the meaning of any one part of it … it is necessary to have some idea of the whole…. People often say of one or another detail or part of this system: “Oh, that is like something I read in a book”, or they say: “Oh, that is like what so and so teaches, or what this or that philosophy or religion says”, etc., etc. It is quite true that if you read certain kinds of literature you will find a sentence here or a sentence there which reminds you of something in this work. But all these are fragments. They are merely separate bits, not in any organized relation with any whole, and, isolated by themselves, are useless.[32]

I would also argue that an important feature this system included which made it “whole,” was a practical methodology. Very specific practices are employed in it to pursue self-knowledge and inner change. These are provided in conjunction with a cosmological framework that explains the individual’s place in the universe and potential for inner growth within it.

This was lacking in other sources Nicoll encountered. One of the biggest problems with so much other Western esoteric material is that while much may share certain ideas about the nature of the universe, and may even speak of the need for self-knowledge and inner transformation, the practical means to pursue this is not made clear. Nothing else Nicoll had found provided a complete system one could follow—at least not in their surviving forms and literature.

This is a recurrent problem one faces when looking at the remnants of Western esoteric or mystic traditions, as the religious scholar Arthur Versluis has noted:

This problem is the more galling the more one studies the history of Western mysticism. And that is: What practices did this or that figure undertake in order to realize transcendental or non-dual consciousness? We almost never know. That is true of almost the entire history of Western mysticism.[33]

Referring to “Platonism, Gnosticism, and Hermetism”—traditions Nicoll had previously studied—Versluis goes on to explain how the textual absence of specific practices sets Western traditions apart from those in the East, which do often describe practices in their texts:

In Platonism, Gnosticism, and Hermetism, and in mysticism through medieval into modern times, the classical mode in the West has been not to include meditation instructions or particular practices [in texts]. Even those kinds of spiritual advice one does find … does not extend to exactly what and how one ought to proceed in the more specific manner of Buddhist or Hindu meditation or practice instructions.[34]

But, in contrast, the Fourth Way did provide a system with practices by which a person could reputedly gain self-knowledge, experience higher states of consciousness, and undertake a process of self-transformation—although at first, the methods were only explained by oral transmission in groups. The first public Fourth Way books were not published until 1949, when Gurdjieff gave permission to share the knowledge more widely.

Today, our situation is very different: with the rise of the new age movement our culture is saturated with spiritual practices in literature and media of all kinds, in what has become an increasingly commercialised “market”. There has been a massive influx of Eastern practices and ideas along the way, particularly in the latter half of the 20th century, although oftentimes with much cherry-picking and distortion in the process.

But all that came later. In the early 1920’s, the Fourth Way was quite a unique phenomenon in the West. Although there was already a groundswell of interest in esotericism and Eastern knowledge, spurred in large part by the Theosophical movement founded by H.P Blavatsky, the kind of applied spiritual practice Gurdjieff offered where theory and practice were presented together as a unified system—more in the guise of an “esoteric school” where the primary focus is on practice—was sorely lacking. No wonder going to Ouspensky’s lecture was such a pivotal moment for Nicoll.

It is the practical side of the system that is usually meant by the term “The Work”. Nicoll emphasized however, that the cosmological teachings interconnect with the practical, psychological side, as “it is all about raising the level of Being to unity.”[35] Put simply, the cosmology lays out a vision of what to aim for and why, and the practical side provides a means to purportedly reach and experience these possibilities. And this, I think, is what made Nicoll view and appreciate this system as an “organic whole”.

Present Moment Practice: Self-Observation and Self-Awareness

The most important psychological practices of The Work—certainly in Nicoll’s presentations— are “self-observation” and the closely related exercise of “self-remembering” or “self-awareness,” which are explained by him in detail. There is much that could be written about these concepts, but, for now, the following samples from Nicoll’s Psychological Commentaries should give enough of an overview.

Unless you have got to the point of understanding that this Work, and all esoteric psychology, is about your inner states and deals with your reactions to others who act on you, it will all seem vague, fantastic and unnecessary. Self-Observation, the starting-point of this Work, is to make one realize one’s inner states. Evolution is an evolution of inner states. Self-development is a development of inner states. Only you can know your inner states: only you can separate from useless, negative or evil states. I repeat that it is impossible to become more conscious … unless you have begun to be aware of what kinds of things are in you and go on in you, and for this to occur it is necessary to turn the attention inwards first of all and notice your reactions to the outer. But you must also notice the outer.

[In] the state of consciousness called “Self-Remembering” … a man is aware of himself and of all he sees round him, and at the same time aware of all the thoughts and feelings passing through him.

A higher level of being lies immediately above all of us at this very moment. It does not lie in the future of time but in ourselves at this very moment, now. All work on oneself, all personal work which deals with stopping negative emotions, with self-remembering, with not being identified with one’s woes and troubles … is concerned with a certain action that can take place in oneself at this moment—now—if one tries to be more conscious and remembers what it is we are trying to do in this work. That is to say, the work is about a certain transformation of the instant, of the moment, of the present, through the action of this work.

Briefly summarized, bringing one’s attention to the present moment, and turning that attention inwards to be aware of one’s automatic thoughts, emotions and reactions as they occur in response to daily life—and observing these with detachment so one is less driven by blind reactivity, and can respond more consciously instead—is a major focal point of The Work. It was this that Nicoll emphasized and retuned to over and over in his five volume commentaries, stressing that “self-observation … is the continual task of all connected with my Branch of this Work.”

Towards the end of the 20th century, the similar practice of mindfulness, derived primarily from Buddhism but presented in a secularised form to be applied, successfully, to mind-body health applications, would become mainstream in the West.[36] But it is worth noting that Gurdjieff had introduced a similar practice earlier—although, in a manner more akin to Eastern and other traditional approaches to spiritual education (including those from which mindfulness is derived) this was done within an overarching spiritual system that, while undoubtedly modified for a Western setting, still required certain discipline and commitment to learn and study. (Aside from these contextual differences, there are also certain differences in approach between the exercises themselves, but that is not relevant to the present discussion).

Amongst early Fourth Way figures however, it was Nicoll’s particular way of communicating the practical psychological exercises of the system that I think permeates most directly into today’s modern, popularised, new age spirituality. His books, it seems, took the self-knowledge exercises to a wider audience beyond Fourth Way groups. This is largely due to the large volume of material he produced early on describing these practices in detail and depth, and the dynamic flair with which he did so. I think his lasting influence can still be seen and felt, even if certain aspects of the system he and his predecessors conveyed that do not resonate with the new age “feel good” zeitgeist—such as the constant emphasis on the need for inner work, struggle and effort—tend to get de-emphasized, in some cases obliquely derided or, mostly, simply ignored and left out the picture.

One example of Nicoll’s influence permeating further afield can be seen, I believe, in his discussions on the spiritual importance of now. In Living Time, the first book he wrote dealing with such ideas,[37] Nicoll outlined, in a more philosophical way, the importance of bringing greater awareness and consciousness to the present moment in ways that finds echoes within today’s modern spiritual vernacular. Long before popular modern authors pointed to the need to be conscious in the present moment to awaken, as for instance Eckhart Tolle does in The Power of Now, Nicoll wrote of the “Creation of Now”—a chapter title and phrase used in the book—to describe the act of becoming conscious in the present, which will “create” the “feeling of now” in which “one is” and inner growth is possible.[38] [39] Nicoll writes: “The object is to reach a state of consciousness – a new state of oneself. It is to reach now, where one is present to oneself.”[40] In his Psychological Commentaries, Nicoll would elaborate that “now” is the only point one can experience a timeless vertical dimension that intersects the horizontal dimension of time at every moment, and that the present “only becomes now in its full meaning if a man is conscious.”[41] He used the Christian cross to represent this diagrammatically a number of times, with the horizontal line representing passing time flowing from past to future, and the vertical corresponding to eternity and states or levels of being—higher timeless states being attainable when one is conscious now. Later writers, such as Tolle, have also expressed similar ideas along comparable lines.

Drawing on Wider Influences to Synthesise “Esoteric Psychology”

I believe that part of what made Nicoll’s work compelling, was his creative ability to seamlessly infuse wider spiritual influences into his Fourth Way expositions, but in ways that shed greater light on its ideas, rather than altering them. To a certain extent his own work presents a synthesis of what he called “esoteric psychology”—the timeless knowledge concerned with the inner transformation of the individual—of which The Work, in his view, provided the most complete modern description for the times. But he pointed out the underlying principles of esoteric psychology had been expressed in other systems nevertheless.

All esoteric psychology has this central idea [of inner transformation]. In fact, that is why it exists. It is always about how to attain this possible inner change or transformation. In some systems it is called re-birth or regeneration, which is the same thing.[42]

Thus a number of older teachings, however fragmented or incomplete their remnants may have become in modern times, also share a number of central ideas about inner transformation, since “all Esoteric Psychology is the same” in its fundamentals.[43] He once explained that, having found and grasped the fuller picture of the “clear and connected” Work system, he could recognise any useful aspects from his past studies of esoteric literature and let these “fall into their right place” within the broader picture of esoteric psychology the Work had revealed to him.

Now [when I committed to The Work] I had already studied at different times in the past the Gnostic literature, the Neo-Platonists, the Alchemists, some of the Indian Scriptures, the Hermetic writers, the Sufi literature, the Bible, the Chinese Mystics, the writings of [Meister] Eckhart, Boehme, Blake, Swedenborg and others, and had been a pupil of Jung for some years…. But it did not mean that my [previous] studies had been useless…. They now enabled me to see how strong and clear and connected the Work was by comparison. What I had to do now was to study the ideas and the methods of the Work. Anything useful gained from the past would then fall into its place.[44]

Nicoll particularly emphasized that “the esoteric teaching in the Gospels” was essentially “the same” as the Fourth Way, although the terms differed and the ideas were not “arranged in the right order” in the scriptures.[45] Now Gurdjieff was recorded saying, almost offhand, that the Work “is esoteric Christianity,” and he also referred to the Gospels and spoke very highly of Jesus on occasion, while also pointing out the knowledge within these texts, at least in their surviving form, was no longer properly connected.[46] Nicoll acted upon these notions and took them further, making it something of his personal mission to help people view and understand the Gospels as a form of esoteric psychology concordant with the Work; he sought to interpret and explain their contents so their teachings could once again be properly connected and understood by modern people in this deeper sense. Nicoll wrote poignant reflections on what he understood to be the inner esoteric meaning of the parables, teachings and events of Jesus’ life, detailing what they communicated about a universal psychological process of inner development. These are recorded in his books The New Man and The Mark, and are interspersed throughout his Psychological Commentaries. The result of this emphasis is that his work is profusely “Christ-centric,” as one writer puts it, in ways that Gurdjieff’s and Ouspensky’s simply was not (even if they did refer to the Gospels at times).[47]

One example of a more modern influence being incorporated, however, is that of Jung. Now there is nothing I am aware of in Gurdjieff’s own work about studying one’s dreams for self-knowledge. Nevertheless, as the vivid dream related at the start of this article demonstrates, Nicoll as a Fourth Way teacher clearly continued to view dreams as a window into the psyche that could reveal insights into one’s inner condition and self-development journey. And he—rather brazenly—sought to demonstrate how this could be the case even after openly acknowledging that, technically speaking, “the study of dreams as a psychological method of approach to oneself is definitely discouraged” in the Fourth Way.[48]

And aside from Jung, there were also other influences that Nicoll incorporated. Gary Lachman, a noted writer on esoteric topics and history, was struck both by Nicoll’s “warmth and bedside manner that humanizes what can often be presented rather solemnly and sanctimoniously,” but also by his “knack” for blending in wider influences, when he re-read the commentaries after many years:

Recently I had occasion to reacquaint myself with Nicoll’s Commentaries…. What struck me this time around was Nicoll’s knack of blending non-Work insights and ideas into his weekly sermons. (His father had been a minister.) This is not to say, as some purists might, that Nicoll watered down the teaching. Not at all….

Readers familiar with Swedenborg, Neoplatonism, and Jung who find their way to the Commentaries can enjoy, as I did, discovering Nicoll’s veiled references to these influences—which, as the years went on, became less and less veiled. For instance Nicoll’s advice that whatever we dislike in another we must look for in ourselves seems a close cousin to Jung’s admonitions about embracing our shadow. As Nicoll said, “an increase in consciousness . . . would result from bringing the dark into the light.” When he points out that our “inner psychological invisible country” possesses its own “heaven, hell and an intermediate place,” his description of our interior world strikes a Swedenborgian note, as readers of Swedenborg’s Heaven and Hell will know.[49]

However, it must be pointed out that when Nicoll incorporated wider influences, he did so in a way that conformed and harmonised them to the Fourth Way system and its objectives, rather than the other way around. In other words, any relevant pieces and insights fell “into their place” within that superstructure, and appeared purposefully—carefully mediated by his personal insight and understanding.

Dreams are a clear example of this: Nicoll’s way of understanding and interpreting dreams developed markedly from a Jungian perspective into one that was integrated and understood in terms of the Fourth Way’s cosmology and psychological model—as his lectures on dreams in his Psychological Commentaries clearly shows.[50] Instead of ascribing transpersonal dreams to Jung’s “collective unconscious”, Nicoll identified a different source for what he called an “esoteric dream”—viewing them as “influences com[ing] down the Ray of Creation from higher levels” being communicated via “Higher Centres” in the psyche[51]—and his way of interpreting their meanings became aligned to the psychological principles of “The Work.” He also connected the language of such dreams to that of the Gospel parables, indicating both symbolically conveyed inner psychological meaning concerned with self transformation, in a common language coming from a higher level of understanding and being than our own. Thus Nicoll was inspired by, and remained broadly in agreement with, the Jungian perspective that studying dreams could be useful for one’s inner development, yet he profoundly shifted his perspective on dream analysis to align with The Work.

As briefly alluded by Lachman in the quotation above, another area where Jung influenced Nicoll is in his discussions of “the light of consciousness” and “the dark side” of one’s psychology— tantamount to “the shadow” in Jung’s system. But again, Nicoll’s perspective was adapted to the Fourth Way. He came to view “the method of self-observation” as the primary practical means to gain self-knowledge and bring the dark unconscious side of one’s psyche into the light of consciousness,[52] rather than, for instance, the method of third-party analysis found in analytical psychology. Nevertheless, Jung clearly influenced Nicoll’s perspective in this area—a fact that Nicoll acknowledges in his commentaries.[53] As Beryl Pogson, Nicoll’s biographer and secretary of 14 years puts it: “He incorporated many of Dr Jung’s ideas into his later teaching and was always aware of his debt to him.”[54]

Interestingly, sometime after Jung dreamt that he and Nicoll were working on the same psychological tree but Nicoll at a higher level than himself, Nicoll had a similar dream where both men worked on different branches of the same tree, and Jung discovered something on his that he brought back with much excitement. Could this perhaps represent Jung’s insights on the unconscious and how dreams could be studied for self-knowledge? Whatever the case, Nicoll not only incorporated and adapted dream interpretation into his lectures, but also into private discussions with pupils.[55]

I get the distinct impression that Nicoll never forgot the insight from his “moment of consciousness” as a young boy in Sunday school: “inner individual authentic perception … is the only source of real knowledge.” Having authentic, clear, conscious inner perception, and increasing it, is one of the primary objectives of The Work—and Nicoll trusted his. The example of how his views on dreams evolved and were synthesised and incorporated, shows he had the flexibility, creativity and self-confidence to recognise when something could serve the overarching self-knowledge objectives of “the Work,” even when it was not strictly canonical to the system, provided it was approached with a genuine understanding of how it fit. But if he was something of a maverick in making such conscious contributions, he was not an iconoclast. Thus when he shed new light on the psychological ideas of the system he taught, and introduced wider influences, he still managed to remain faithful to its principles and objectives.[56] So much so that Gurdjieff’s nominated successor in France, Jeanne de Salzmann, who led the Gurdjieff society after his passing, said Nicoll’s commentaries provided, “the exact formulation of Gurdjieff’s ideas without distortion.”[57] [58] In spirit I think this is true. Without distortion, certainly, but not without addition.[59]

It was Nicoll’s dynamism—an energetic pragmatism rather than dogmatism— that I think makes his work original and compelling. And despite his tendency to go “off script” with an approach that contrasted with Ouspensky’s intellectual exactitude, Nicoll was very clear and careful to distinguish his “commentaries” from the sanctioned ideas of the teaching itself as he had received it, leaving it for people to decide for themselves whether what he added “by way of commentary” was of any use. As it turns out, much to Nicoll’s surprise, many beyond his immediate circle did see value in his commentaries after all; they were written week-to-week to suit the needs of time and place and were never meant for wider publication, but became his most popular and influential work and remain so today. His friend and colleague Kenneth Walker wrote: “They will remain the standard work on the subject for as long as these ideas are of interest to mankind.” [60]

Maurice Nicoll in 1953

Closing Comments

While Nicoll was very much a Fourth Way teacher, there is something quite unique and compelling about his approach. One of his major hallmarks was the seamless integration of wider esoteric influences beyond the Fourth Way, enlivened by his personal understanding and insights, to elucidate a broader and clearer understanding of “esoteric psychology”—which he indicated was ultimately a timeless field of self-knowledge finding expression in different teachings throughout time. Pertinent threads from Western Esotericism and psychology concerning self-knowledge and inner change converge in ways that just make sense. His ability to do this effectively based on his own personal insights and studies, and his down-to-earth and practical way of explaining the subject, is perhaps one of the primary factors that has made his work enduring and compelling and has given it—however inconspicuously—a wide impact and influence.

There is only so much I can cover in this introductory article, and many points I could discuss further or add, but I only wish for now to give a sense of why Maurice Nicoll’s work warrants greater attention. I think I’ve accomplished that. I intend to explore some of the matters I’ve raised in this post, and more, in greater detail in future articles.

Biographical Bibliography

Jeffrey Adams, The Swedenborgian Tree Gracing Maurice Nicoll’s Garden of Esoterica (Swedenborg Foundation, September 6, 2018) https://swedenborg.com/scholars-the-swedenborgian-tree-gracing-maurice-nicolls-garden-of-esoterica/

Samuel Copley, Portrait of a Vertical Man: An Appreciation of Doctor Maurice Nicoll (London, Swayne Publications, 1989)

GGurdjieff.com, Maurice Nicoll: 20th Century Psychologist and Philosopher, https://ggurdjieff.com/maurice-nicoll/

Bob Hunter, Combining Good and Truth Now: An Homage to Maurice Nicoll, Gurdjieff International Review, Spring 2000 Issue, Vol. III (2) https://www.gurdjieff.org/hunter1.htm

Gary Lachman, Maurice Nicoll: Working Against Time, Quest 106:2, pg 24-28 https://www.theosophical.org/publications/quest-magazine/4456

Maurice Nicoll, Psychological Commentaries on the Work of Gurdjieff & Ouspensky (York Beach, Red Wheel/Weiser, LLC, 1996 [First published London, Robinson & Watkins, 1952])

Beryl Pogson, Maurice Nicoll: A Portrait (New York, Globe Press Books, 1987 [First Published London 1961])

The Enneagram in the Healing Tradition, Maurice Nicoll: Spiritual Giant, Gentle Genius, http://enneagramresourcesinc.com/articles/maurice-nicoll-spiritual-giant-gentle-genius/

The Gurdjieff Legacy Foundation Archives, Maurice Nicoll (1884–1953), http://www.gurdjiefflegacy.org/archives/mauricenicoll.htm

John Patrick Willmett, Maurice Nicoll and the Kingdom of Heaven: a study of the psychological basis of ‘esoteric Christianity’ as described in Nicoll’s writings (The University of Edinburgh, 2017) 63-64 https://era.ed.ac.uk/handle/1842/31220