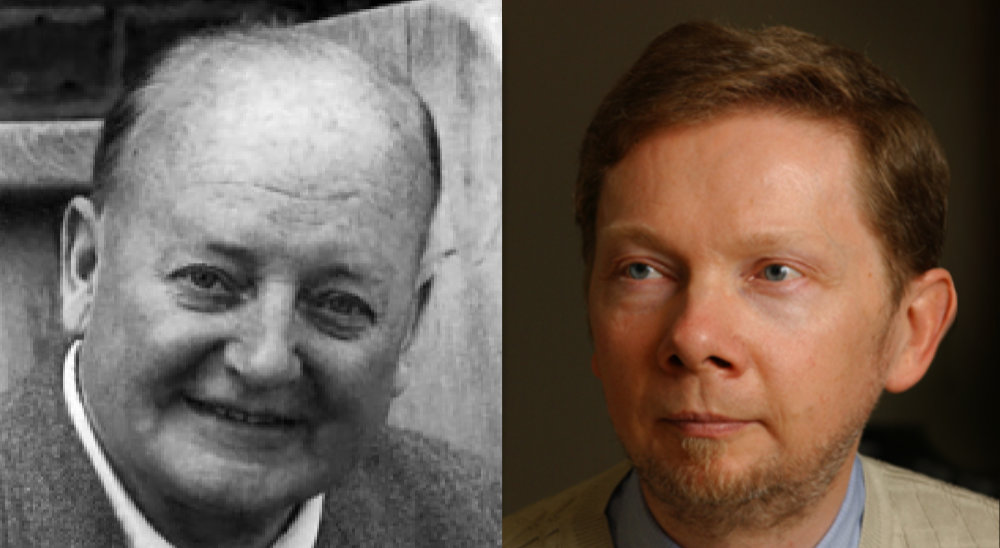

The way Eckhart Tolle teaches self-observation, an inner practice for self-change, has much in common with Maurice Nicoll’s earlier writing on the subject.

I’ve been exploring Maurice Nicoll’s unrecognised influence for some time now. Across a series of articles, I’ve highlighted close correspondences between this Fourth Way teacher’s work and that of Eckhart Tolle—a bestselling author ranked among the most spiritually influential people in the world today.[1] While Nicoll, who died in 1953, is unknown to most, these similarities suggests his cultural impact is, indirectly at least, very significant.

At the core of each authors’ work lies the present-moment practice of self-observation. This is the main method they give for self-knowledge and inner transformation, and I’ve written a detailed comparative analysis on their commonalities in a multi-part series. It’s quite an extensive read however.

To bring their correspondences more into focus, I’ve selected the most similar extracts I discovered and presented these in the format used in my previous article: two-column tables, juxtaposing similar statements side-by-side. While I can’t capture everything I’ve discussed this way, it does make their overall commonalities clearer to see and my research findings more accessible.

This article draws mainly from the first part of my self-observation series, “Being the observer.” It looks at the similar ways the authors explain how to practically do this exercise. In future posts, I’ll share comparative tables on some other aspects of the practice too.[2]

The extracts compared below show a close correspondence between these authors. Tolle can be seen not only expressing the same general ideas as Nicoll, but, at times, using similar or equivalent language too. Some distinctive expressions like “power of self-observation,” and “gramophone records” appear word-for-word, and are used in similar contexts with the same meanings.

As in my last article, quoted text is bolded or underlined in places to emphasise key commonalities, but italics are original to the source material.

Practicing Self Observation

| Maurice Nicoll | Eckhart Tolle |

| ‘Self-observation is an act of attention directed inwards—to what is going on in you.’[3] | ‘Monitor your mental-emotional state through self-observation. . . . Direct your attention inwards.’[4] |

| ‘Notice what thoughts crowd into your mind . . . what they are saying, what unpleasant emotions surge up, and so on.’[5] | ‘Have a look inside yourself. What kind of thoughts is your mind producing? What do you feel?’[6] |

| ‘You must try to observe everything in yourself at a given moment—the emotional state, thoughts, sensations, intentions, posture, movements . . . and so on.’[7] | ‘Give attention to your behavior, to your reactions, moods, thoughts, emotions, fears, and desires as they occur in the present.’[8] |

| ‘The power of self-observation is an inner sense, rarely used. . . . We are unaware of what we are doing.’[9] | ‘You need to have some power of self-observation, which is another word for awareness.’[10]</sup |

| ‘By practice you can observe your mood more and more distinctly.’[11] Through use ‘the power of self-observation’ can ‘be developed.’[12] | ‘With practice, your power of self-observation, of monitoring your inner state, will become sharpened.’[13] |

| ‘Observe … without criticism or analysis.’[14] ‘It is not a critical . . . judging consciousness, but an awareness’ which ‘says nothing but merely shews you what is going on in yourself.’[15] | ‘Don’t judge or analyze what you observe.’[16] ‘Watch . . . not critically or analytically.’[17] It ‘should not be confused with judging… It’s like a mirror showing you what’s there.’[18] |

| ‘People . . . mistake thinking for observing. To think is quite different from observing oneself. . . . The observation of one’s thoughts is not the same as thinking.’[19] | ‘[This] does not mean that you start thinking about it. It means to just observe.’[20] ‘Don’t think about it. . . . Be the observer of what is happening inside.’[21] |

| ‘It is a very good thing to ask oneself sometimes: “In what state am I?”’[22] ‘Get to know where you are in yourself. Ask yourself: “Where am I?” With what thoughts and emotions are you going . . .?’ [23] | ‘“Am I at ease at this moment?” is a good question to ask yourself.’[24] ‘Make it a habit to ask yourself: “What’s going on inside me at this moment?”’[25] |

| ‘Self-observation is a means of self-change. Serious and continuous self-observation . . . leads to definite inner changes in a man. . . . This requires directed attention.’[26] | ‘Deep unconsciousness . . . usually needs to be transmuted through acceptance combined with the light of your presence—your sustained attention.’[27] |

Observing “inner talking” or “the voice”

| Maurice Nicoll | Eckhart Tolle |

| ‘Inner talking’ is a mental ‘monologue’ that can repeat like ‘old laid down gramophone records’ internally.[28] | ‘The voice’ consists of ‘continuous monologues or dialogues’ which can repeat like ‘old gramophone records . . . playing in your head.’[29] |

| It is ‘negative in character.’[30] | Has an ‘often negative nature’[31] |

| ‘This inner talking . . . goes on in you all the time.’[32] | ‘Virtually everyone hears a voice . . . in their head all the time.’[33] |

| It’s comparable to ‘people who go along in the streets muttering to themselves’ but it’s usually ‘not expressed outwardly.’[34] | It’s like ‘people in the street incessantly talking or muttering to themselves’ only most ‘don’t do it out loud.’[35] |

| It ‘drain[s] force from us uselessly.’[36] ‘It is a continual source of leakage, of force.’[37] |

It ‘drains them of vital energy’[38] ‘It causes a serious leakage of vital energy’[39] |

| ‘The first thing that we must do in regard to inner talking is to observe it and notice what this inner talking is saying.’[40] | ‘Start listening to the voice in your head as often as you can. Pay particular attention to any repetitive thought patterns.’[41] |

| ‘Now when you observe a thought, you are not identified with it.’[42] | ‘As you start listening to the thought . . . you are no longer energizing the mind through identification with it.’[43] |

| ‘You are not your thoughts.’[44] | ‘You are not your mind’[45] [46] |

Identification and non-identification

| Maurice Nicoll | Eckhart Tolle |

| Inner ‘identification’ occurs when we ‘say “I”’ or give “the feeling of “I”’ or ‘sense of “I”’ to our inner states (emotions, thoughts etc.).[47] | ‘Identification’ occurs when ‘mental-emotional patterns . . . are invested with a sense of I, a sense of self.’[48] |

| You ‘become’ whatever state, thought or reaction you ‘identify with’ and they ‘become you.’[49] | Through ‘identification with’ an emotion it ‘temporarily becomes “you”’[50] |

| If you ‘identify with’ an ‘opinion’ then ‘the feeling of “I” becomes fastened to it.’[51] | ‘If you identify with a mental position, then if you are wrong, your mind-based sense of self is seriously threatened.’[52] |

| ‘The more often we identify with something, the more we are slaves to it.’[53] | Through being ‘unconsciously identified’ with the mind ‘you are its slave.’[54] |

| ‘Whatever we identify with’ in us ‘has power over us’[55] and we ‘lose force to it.’[56] If you observe and consciously stop identifying with thoughts and emotions they ‘will not have full power over you.’[57] | ‘Through identification with’ compulsive thoughts you are ‘energizing the mind,’ but a thought ‘loses its power over you’ whenever you consciously witness and stop identifying with it.[58] |

| ‘Self-observation is to make things in yourself more and more conscious to you, so that you can say: “This is not ‘I’ “. Otherwise you are glued to them and under their power—that is, identified with what is not you. They then act on you unconsciously—often in terrible and morbid ways. But you remain unconscious of them, taking it all as ‘I’. So you are not conscious of them.’[59] | ‘Most people are at the mercy of that voice [in their head]; they are possessed by thought, by the mind. . . . When you are identified with that voice, you don’t know this, of course. . . . You are only truly possessed when you mistake the possessing entity for who you are. . . . humanity has been increasingly mind-possessed, failing to recognize the possessing entity as “not self.”’[60] |

| ‘[When] you become conscious that you are identified with something . . . you draw force from it. . . . To identify means that force is taken away from you: to non-identify means that you take the force away from what you identify with.’[61] | ‘Identification with the mind gives it more energy; observation of the mind withdraws energy from it.’[62] |

| ‘The mechanical side will lose force and there will be a gain on the conscious side.’[63] | ‘The energy that is withdrawn from the mind turns into presence.’[64] |

| Note: Nicoll uses the term “non-identify,” or its variants, to describe overcoming identification—separating from what is transient or false in one’s psyche by consciously observing it in the present-moment.[65] | Note: Tolle uses the term “disidentify,” or its variants, to describe the act of breaking identification—separating from what is transient or false in one’s psyche by consciously observing it in the present moment.[66] |

Being the observer

| Maurice Nicoll | Eckhart Tolle |

| When ‘observing yourself’ you are not ‘identified with your state.’ You are ‘standing outside your state . . . independent of it, and . . . looking at it.’[67] You ‘step back from’ it and ‘separate from it’ and ‘watch it,’ seeing it ‘no longer as you.’ [68] | ‘The ability . . . to observe’ and ‘to “watch”’ thoughts and emotions ‘without being identified’ brings ‘a [sense of] “standing back”’ from them.[69] There’s a ‘“standing back” from [a] thought and looking at that thought’[70] which brings about ‘the separation of consciousness from its identification.’[71] |

| With self-observation, you stop seeing yourself ‘as one’ but ‘become two’[72] or ‘divide yourself into two—an observed side and an observing side,’[73] into ‘IT and Observing “I”’[74] (with ‘IT’ being ‘the Personality-Machine’[75] or ‘False Personality’[76]). When someone ‘begins to observe himself, he will then, at that moment, become two’ and stop ‘identifying . . . with everything that happens in himself.’[77] | Observing a thought made Tolle ask himself: ‘Am I one or two?’[78] ‘I saw that I was “two,”’ he explains. There was a ‘mind-made fictitious entity’ (the egoic false self) behind the thought and the ‘“I” consciousness’ that was ‘looking at . . . the structure of that thought.’ ‘At that moment a dis-identification happened’ from the mental-emotional content he was observing.[79] |

| “The impressions gained from self-observation are . . . from an internal sense . . . a silent witness, a spectator of what goes on in me”[80] | ‘A clear and still space of pure awareness . . . come[s] into being . . . the silent witness, the watcher.’[81] |

| ‘Observing ‘I’ is not identified with what it observes. . . . If you can observe your thoughts and worries, then you establish the starting-point . . . the new point of growth in you.’[82] | ‘The beginning of spiritual awakening’ is when ‘your whole sense of identity shifts from being the thought or the emotion to being the “observing presence.”’ [83] |

| You ‘shift the centre of gravity of consciousness by becoming conscious of what you were not previously conscious of’[84] in you, and increasingly ‘feel the sense of “I” in Observing “I” and not in the observed side’ of your psychology.[85] This will ‘take the feeling of “I” out of’ what you observe in you,[86] as ‘what you observe distinctly you are not identified with.’[87] | By becoming aware of unconscious ‘thoughts, emotions and reactions’ you undergo ‘a shift’ in your ‘sense of self’ from inner states to ‘the conscious Presence that witnesses those states.’[88] This ‘observing presence’ is beyond ‘those things that you observe,’[89] and a ‘disidentification’ from the latter ‘happens automatically’ this way.[90] |

| This ‘Observing I’ is ‘a point of consciousness that is independent of your moods,’[91] a ‘broader and deeper consciousness.’[92] | This ‘observing presence’ is ‘behind the content of your mind.’[93] It is ‘pure consciousness beyond form.’[94] |

| ‘Consciousness is not the same as your thought, feeling or sensation. Through consciousness you become aware of them as contents, but . . . consciousness can exist without any content.’[95] | ‘Thinking and consciousness are not synonymous. . . . Thought cannot exist without consciousness, but consciousness does not need thought.’[96] ‘Your conscious presence [has] no content.’[97] |

| ‘Once we see . . . a thing recurring in ourselves through the inner sense of self-observation, we are gradually freed, gradually made less and less under its power. Why?—through the increase of consciousness. All increase of consciousness renders mechanical behaviour less dominating.’[98] | ‘Whenever you watch the mind, you withdraw consciousness from mind forms, and it then becomes what we call the watcher or the witness. Consequently, the watcher—pure consciousness beyond form—becomes stronger, and the mental formations become weaker.’[99] |

Laughing at oneself

| Maurice Nicoll | Eckhart Tolle |

| ‘Now if you are observing your thoughts and your emotions . . . you may [after a time] laugh at these thoughts, these emotions, and wonder why you took everything in that way.’[100] | ‘When you detect egoic behavior in yourself, smile. At times you may even laugh. How could humanity have been taken in by this for so long?’[101] |

| ‘[When] what is conscious—that is, the light—meets what was operating unconsciously [in you] . . . self-love is diminished, and consciousness increases at its expense. It is wonderful to catch a glimpse of your self-love and be able to laugh at it. One loses the former highly-explosive over-sensitive feeling of ‘I’ more and more.’[102] | ‘Every time you create a gap in the stream of mind, the light of your consciousness grows stronger. One day you may catch yourself smiling at the voice in your head, as you would smile at the antics of a child. This means that you no longer take the content of your mind all that seriously, as your sense of self does not depend on it.’[103] |

Concluding comments

These direct comparisons show that Eckhart Tolle mirrors, in many aspects, how Maurice Nicoll explained how to practise self-observation when teaching the Fourth Way.

Both authors describe self-observation as attention directed inwards that lets us see our thoughts and emotions occurring in us in that moment. This is a silent awareness, they say, showing us our inner state as it is without any thinking, analysis or mental judgement. They tell us the “power of self-observation” increases the more we use it, and suggest that we pose questions to ourselves to prompt self-observation.

Both emphasise observing the compulsive, habitual internal thought monologue happening in us “all the time,” which Nicoll calls “inner talking” and Tolle calls “the voice.” This is usually negative, both insist, is often repetitive like old “gramophone records,” and they compare it to people “muttering to themselves” in the street, only not expressed out loud.

Using self-observation to overcome habitual identification with our unconscious inner states is a central idea in both authors’ work, and the modus operandi of the practice itself. They explain it does this by shifting our feeling or sense of “I” or “self” into the observing consciousness—which Nicoll calls “Observing I” and Tolle calls “observing presence”—while simultaneously withdrawing it from any inner psychic content that can be observed. Both describe how a sense of being “two” arises as we do this, as a separation occurs between the observing consciousness, which they say has no content, and the psychological “content” observed. One can feel themselves inwardly standing or stepping back from thoughts or emotions as this happens.

Consciousness is said to increase or grow in strength the more we do this, while the power of unconscious inner states observed in this way diminishes. Interestingly, both say we can gain the capacity to laugh at ourselves—or at habitual thoughts and emotions in us—if we continue with this.

It is quite clear there is a close correspondence in how Nicoll and Tolle describe this practice; they present equivalent points with similar language—sometimes using the same examples and terms.

This comparison has focused mostly on their take on the “how to” of self-observation, which, as mentioned earlier, I’ve already written extensively about before but have summarised here.[104] I’ve also previously looked at the corresponding ways Nicoll and Tolle describe this practice effecting an inner esoteric transformation as “the light of consciousness” grows or increases, and also changing how one experiences life for the better. I’ll summarise these other similarities in the same format used here, and more, in future posts.